한올가Khan Olga (SNUAC)

구소련 지역의 한인은 이질적이고 다민족적인 환경에서 동화되었다. 다양한 민족을 대표하는 사람들과 끝없이 접촉하고 다양한 문화에 노출되면서 한인들은 다민족적 환경에 유연하게 대응하는 심리적 태도와 쉽게 적응하는 행동 방식을 습득했다. 동질적인 한국 사회에 산 한국인들과는 달리 한인들은 다민족적 환경에서 수십 년간 생활했고, 그 과정에서 한민족 본래 문화의 많은 요소가 변형되거나 상실되었다. 중국, 일본, 미국과 세계 다른 지역의 한인들과 마찬가지로 구소련 지역의 한인들도 한반도의 한국인과 크게 달라졌고, 그 결과 “고려인”이라는 별개의 민족 집단이 등장했다. 그러나 한반도의 한국인과 고려인 사이의 가장 큰 차이점은 바로 고려인 문화가 한국, 러시아, 소련, 중앙아시아, 유럽 문화가 혼합된 결과라는 것이다(Khan 2011). 중앙아시아 고려인의 중층적이고 복합적인 정체성은 문학, 노래, 그림 등 다양한 예술로 나타났다. 그러나 소수 집단에 속한 이주자로서 고려인의 경험을 다룬 영화는 드물며, 다른 한인 디아스포라 공동체와 비교할 때 이 점이 더욱 분명하게 드러난다. 고려인 영화는 다른 예술 분야보다 역사도 짧고 창작자 수와 작품도 적으며, 한국, 미국, 캐나다, 러시아, 중앙아시아의 영화감독, 역사학자, 블로거들이 만든 다큐멘터리나 단편 영상에서도 고려인을 다룬 영화나 영상은 찾아보기 어렵다.

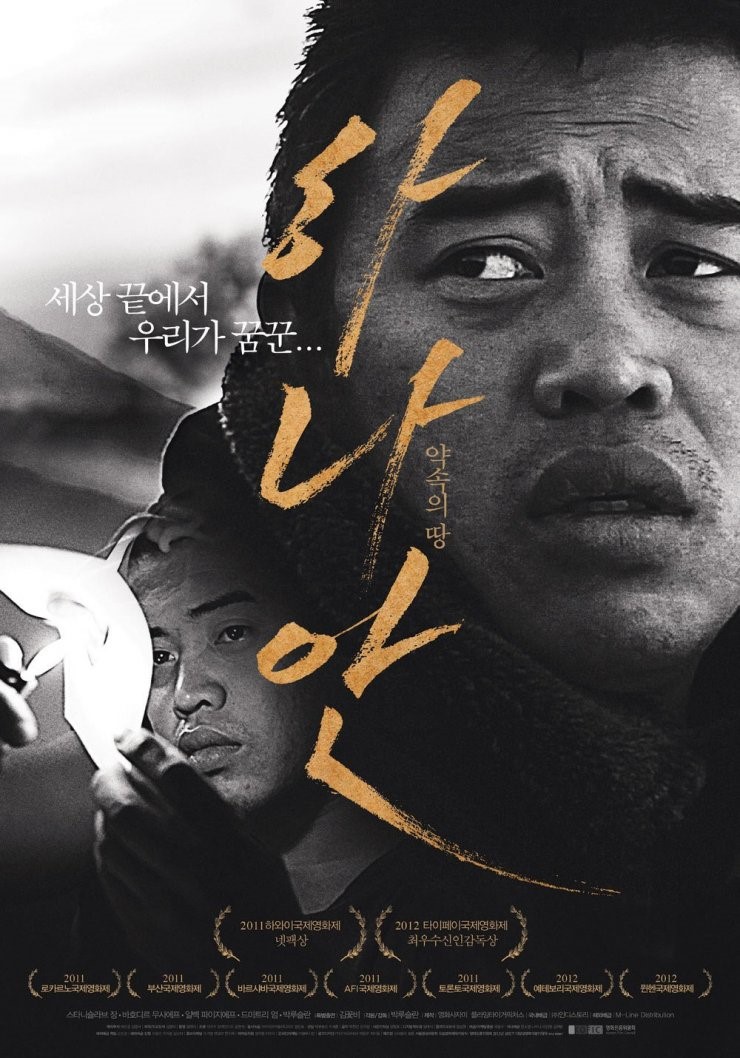

고려인 영화는 새롭게 나타난 현상으로 볼 수 있다. 2010년 최초의 고려인 감독인 루슬란 박(Ruslan Pak)이 <하나안(Hanaan)>이라는 주목할 만한 작품을 선보이기 전에는 우즈베키스탄 고려인은 영화를 만들지 않았으며, <하나안> 이후에 다른 감독이 새로운 고려인 영화를 제작하기까지10년이 더 걸렸다. 많은 다큐멘터리가 고려인의 강제 이주에 초점을 맞춘 것과 달리 신진 감독들은 현대에 “고려인이라는 것의 의미”에 관해 깊이 성찰하고 탐구한다. 이주민 출신 영화 감독들이 “혼성성의 대리인(agents of hybridity)”(De Man 2023) 역할을 하듯이 고려인 감독들도 이질적인 미학을 보여주고 서사 전략을 사용해 문화적 소속감과 독특성을 전달한다. 감독들이 겪은 지정학적 여정과 그들의 사회적 정체성은 영화의 미학과 기원, 이동, 이주에 따른 혼란 등과 관련된 주제를 다루는 방식에 큰 영향을 미친다. 예술가들은 영화를 통해 복합적인 정체성을 전달하고 전통, 언어, 유산을 효과적으로 보여줌으로써 특히 “복잡한 개념과 이주민으로서 살아간다는 설명하기 어려운 상황을 표현해 관객을 사로잡고 빠져들게 할 수 있다” (Son 2012).

감독으로부터 사용 허가를 받음

<하나안Hanaan> (2011), 로슬란 박: 이상과 현실 사이의 간극

고려인 4세인 루슬란 박은 영화 <하나안>을 통해 국제영화제에 데뷔하며 낯선 민족집단인 우즈베키스탄 고려인을 주제로 삼아 자기정체성의 문제를 제기했다. 영화는 소련 시기 우즈베키스탄에서 태어난 고려인 스타스(스타니슬라프 티얀Stanislav Tyan이 연기)가 만연한 상실감에 대응하며 심리적으로 갈등하고 “이상”을 끝없이 추구하는 모습을 그려낸다. 영화 전반에 1990년대를 상징하는 감정이라고 할 수 있는 절망감과 목적 상실감이 스며들어 있으며, 따라서 ‘네오체르누카(neochernukha)’라는 장르로 분류할 수 있다.영화 속에서 소련 붕괴 이후 타슈켄트는 더러운 아파트와 황폐한 빌라의 도시로 그려지며, 고려인인 스타스, 신, 코소이와 백인처럼 생긴 사이드는 마약을 하고 갱단들의 싸움에 휘말리며 시간을 보낸다. 그들 모두 암울한 상황에서 벗어나려고 애를 쓴다. 신은 한국으로 가고 스타스와 나머지 친구들은 마약에서 도피처를 찾지만, 마약을 시작한 이상 삶을 포함해 소중하게 여기는 모든 것을 완전히 잃어버릴 수밖에 없게 된다.

이주자들이 만든 다른 영화처럼 <하나안>은 정체성이라는 문제를 탐구한다. 이주자 영화의 주요 주제인 정체성은 뿌리가 뽑혀져 나갔다는 감정과 “역사적 모국”이라는 개념에 대한 복잡한 심리에서 비롯되어 소속감을 찾으려고 하는 힘겨운 노력과 관련되어 있다. 한국으로 이주한 신은 스타스에게 한국에서 더 나은 삶의 가능성을 찾아보라고 조언하지만, 스타스의 반응은 미지근하다. 스타스가 신에게 “여기서 우리가 가지지 못한 것이 한국에는 있을까?” 라고 묻자, 신은 “바다”라고 답한다. 신과 스타스의 회의적 태도는 모국에 대한 이주자 개인의 애착 강도가 시간적, 공간적 근접성에 따라 다르다는 점을 드러내지만(Oh 2006), 청년들은 역사적 이유로 인해 조상의 고국에 대해 강한 유대감을 드러내지 않는다.[i]<하나안>은 “이상적 조국에 초점을 맞추면 이주 환경에서 형성된 관계와 결속의 중요성은 주변부로 밀려나기 때문에”(Soldavini 2010) 모든 이주자가 조상의 고국에 큰 희망을 품는 것은 아니라는 점을 시사한다. 영화는 스타스와 친구들의 일상 생활에 다문화주의가 깊게 침투해 있으며 이중언어 사용, 다민족적 관계, 여러 민족의 전통음식이 혼합된 요리 등을 통해 나타난다는 점을 보여줌으로써 이주자의 “상상된 본질 또는 순수함”을 뒤흔든다(De Man 2023).

결국 스타스는 한국으로 가지만, 친구의 성공이 마약 거래와 관련되어 있다는 것을 알게 된다. <하나안>은 열린 결말로 끝난다. 마지막 장면에서 스타스는 약속의 땅을 상징하는 바다 앞에 홀로 앉아 있다. 그가 이후 어떻게 됐는지는 영화에 나오지 않는다. <하나안>의 열린 결말은 신화적 고국에 대한 “말로 표현되지 않은” 향수와 귀환이라는 현실 사이에 존재하는 간극을 드러내 고려인들이 한국으로 이주한 뒤에도 조상의 고국에서 계속 “방황”하며 한국이 마지막 목적지가 될 수 없다는 사실을 깨닫기도 한다는 점을 보여준다 (Sim 2019). 영화의 마지막 장면에서 분명히 드러나듯이 ‘하나안’은 잊어버린 고국이 아니다. 주인공이 갈망하는 “고향”은 그의 고국도 그가 사는 나라도 아닌 알 수 없는 “어딘가”로 가는 여정이다(Prime 2016).

<양귀비 필 무렵 When Poppies Bloom> (2019): 고려인 정체성의 재구성

고려인 영화는 아직 발전 단계이며, 감독들은 영상 문화라는 틀 안에서 자신을 표현하는 여러 방법을 실험하고 있다는 점을 염두에 둘 필요가 있다. 그러나 이주자 예술을 분석할 때 영화를 포함하면 “예술을 분석할 때 여러 층위에 있는 재외 한인들의 목소리를 종합함으로써 “상위” 예술과 “하위 예술” 사이의 간극을 통합”(Son, 2012)할 수 있다. 리타 박(Rita Pak)의 <양귀비 필 무렵>이 고차원적인 예술에는 도달하지 못했다고 평가할 수도 있지만, 우즈베키스탄 고려인의 삶과 사고방식을 다루어 고려인의 정체성을 이해하기에 유용한 자료다. 영화는 소년 로마(Roma, 어린 시절은 바딤 킴Vadim Kim이, 성인 시절은 블라디미르 유가이Vladimir Yugai가 연기)가 부모에게서 버림받은 뒤 고려인 집단 농장에서 조부모의 손에 키워지고 공무원으로 성장하는 모습을 그려내는 성공 스토리다. 영화에서 로마는 영웅처럼 어린 시절부터 여러 도전과 개인적 고난을 헤쳐 나가며 성인이 된다.

오늘날의 해석에 따르면 콜호즈는 “고려인 집단 농장”이자 “기억의 공간”이라는 특수한 장소다. 영화의 이야기 대부분은 콜호즈에서 전개되며, 고려인들이 사용하는 특이한 형태의 탈곡기(파이pai)나 과거에 지켜지던 전통과 같은 고려인만의 고유한 문화를 그려내 소련 시기 우즈베키스탄 고려인들만의 독특한 생활상을 조명한다. 영화가 과거를 재현하는 방식에서 가장 중요한 요소는 향수다. 감독은 나이든 세대의 경험을 바탕으로 명절, 화투, 떡 만들기, 환갑 잔치 등의 모습을 그려내어 과거를 사실적으로 재현하고 향수를 불러 일으킨다. 소련 정부가 추진한 “민족 혼합” 정책으로 인해 고려인들이 자신들의 고유한 문화와 정체성을 감추고자 했던 시대적 상황을 배경으로 삼아 영화는 로마가 이질적인 문화적 배경에서 한 개인이자 한인 공동체의 일원으로서 성장하는 모습을 묘사한다. <양귀비 필 무렵>은 어렸을 때부터 개척 시기, 학창 시절, 해군에 복무하던 시기, 공장 생활까지 이어지는 로마의 생애를 통해 “한인 디아스포라가 강제 이주지에서의 혹독한 환경에 적응하는 삶의 방식을 발전시키고 비교적 짧은 기간 내에 러시아 또는 러시아화된 사회에 통합”되었다는 점을 입증한다(Oh, 2006). <양귀비 필 무렵>은 이주자 영화가 ‘민족’보다는 ‘문화적’ 측면에 주목하는 사례로, 과거와 현재에 고려인으로서 산다는 것이 무엇을 의미하는지에 대해 폭넓게 이해하는 방식을 보여준다. 영화는 성인이 된 로마가 도시에서 공장에서 일하는 모습과 동시에 로마의 조부모들이 여전히 콜호즈에 사는 모습을 통해 집단농장에 계속 머무른 고려인과 이주 제한이 해제된 이후 도시로 떠난 고려인 사이의 서로 다른 생활 방식이 동시에 존재했다는 점을 표현한다. 옷차림과 머리 모양 또한 로마가 한인의 전통 유산과는 다른 소련식 양식과 생활 방식을 받아들였다는 점을 의미해 10년 동안 어떤 변화가 있었는지를 묘사하는 한편 산소에서 절을 하거나 한인 음식을 먹는 모습은 그가 여전히 민족적 고향과 문화적인 연결을 유지하고 있다는 점을 말해 준다.

<양귀비 필 무렵>은 고려말과 관련된 사건[ii]을 통해 고려인 정체성의 개념을 재구성한다. 나이든 한인들은 러시아어를 능숙하게 구사하면서도 고려말을 계속해서 사용한다. 로마의 할머니를 연기한 라리사 리가이(Larisa Ligay)는 1970년대 고려인들은 집단농장에서 태어났고 고려말을 할 줄 안다는 점에 부끄러워했다고 기억한다. 그러나 과거에는 소외되었던 언어인 고려말은 오늘날에는 보존해야 할 문화 유산이 되었고, 감독은 일부 장면에서 고려말을 사용하는 모습을 통해 영화의 진정성을 강화했다. 이러한 점에서 볼 때 고려인의 자기 인식이 변화하는 역동성은 흥미롭다. 페레스트로이카 기간에 고려인들은 한국인으로서 강한 정체성을 발전시키고 한국의 본래 문화를 수용하려고 노력했지만, 시간이 흐르면서 정체성과 소속을 더욱 비판적으로 보기 시작했다. 1970년대와 1990년대 고려인들이 경험한 열등감은 자부심으로 발전했고, “타자성”을 통해 고려인들은 단일민족이라는 경계를 넘어 세계적 문화 전통의 한 부분으로서 자신들을 인식할 수 있었다(Khan, 2007).

라리사 리가이(Larisa Ligay)의 <합창단 The Choir> (2019)과 <조약돌 Pebbles>(2023): 고려인 문화의 마지막 자취

영화 <합창단>은 다큐멘터리 필름 국제연구소인 “European Union Focus Cine Lab”에서 제작되었으며, ‘사라져 가는 세계’를 주제로 하고 있다. 감독인 라리사 리가이에 따르면, “<합창단>과 <조약돌> 모두 노년 세대의 고려인에 관한 이야기입니다. 이들은 한때 집단 농장에서 살며 고려말을 사용하던 사람들로, 저에게는 점차 사라져 가는 세계를 상징합니다.”

<합창단>에는 한인, 러시아, 우즈베크인의 요소들이 자연스럽게 융합되어 있으며, 다인종 환경에서 살아가는 고려인의 복합적인 문화적 정체성을 반영한다. 리가이 감독은 합창단원들이 소련의 노래를 연습하거나, 러시아와 우즈베크 음식이 어우러진 즐거운 연회를 준비하는 장면에서 러시아어와 고려말을 함께 사용해 소통하는 장면을 통해 여러 문화 사이에서 살아가는 경험을 성찰한다. 그러나 연습과 연회 장면이 끝난 후, 장면은 일상복을 벗고 한복으로 갈아입으며 무대에 오를 준비를 하는 여성들의 모습으로 전환된다. 합창단원들이 준비를 하는 이 모습에서 부드러운 한국 노래의 허밍이 공간을 감싸며, 집단적 문화 기억을 불러일으킨다. 다큐멘터리는 합창단원들의 클로즈업과 함께 각 지역에서 온 공연단이 대규모 무대에서 “아리랑”을 부르는 영상으로 마무리된다. 일반적인 인식과 달리, 이 영화에서의 “아리랑”은 조국에 대한 그리움보다는 전통적인 고려 사람의 문화의 쇠퇴와 그 마지막 남은 세대를 상징한다.

<합창단>에서 제시한 ‘사라져 가는 세대’에 대한 모티브는 감독의 후속작인 후속작 <조약돌>에서 확장된다. 영화는 집단농장에서 살아가며 현지 고려인 합창단의 여성을 사랑하게 된 한 노인(배우 뱌체슬라프 김Vyacheslav Kim이 연기)의 느린 템포의 삶을 다룬다. 여성의 갑작스러운 죽음으로 인해 벌어지는 안타까운 반전을 그린 이 영화는 시간이 지나며 다양한 풍습이 융합된 우즈베키스탄 고려인의 장례 문화를 보여준다. 영화 속에서 러시아 장례식 악단, 묘지에서 통곡하며 절하는 조문객들, 의례적으로 사용된 흰색 머리 스카프는 고려인의 혼합된 정체성을 보여주는 가시적 상징이다. 리가이 감독은 우즈베키스탄 풍경 속에 고려인의 문화적 배치를 설정함으로써, 조상의 땅과의 연결과 추억을 상기시킬 뿐만 아니라 디아스포라 공동체들이 자신들의 민족적 출신과 그들이 지금 속한 나라에 대해 공유하는 정체성을 그려낸다. 장례를 마치고 난 뒤 주인공은 무덤에서 작은 돌멩이를 주워 상자에 넣는데, 그 상자에는 그가 알고 지내던 고인들을 기리기 위해 모은 돌멩이들이 들어 있다. 영화의 마지막 부분에서 감독은 화면을 통해 고려인들의 역사적 배경에 대한 설명을 제공한다:

“1937년, 약 7만 5,000명의 한인이 극동 지역에서 우즈베키스탄으로 강제 이주를 당했다. 이주한 한인들은 행정적으로 추방된 신분이었고, 제한된 권리를 가지며 중앙아시아를 벗어날 수 없었다. 그들은 타슈켄트 지역의 미개간지, 아랄해 연안, 아무다리야강 하류의 황무지에 정착했다. 이주민들은 222개의 집단 농장에 합류했고, 추가로 50개의 고려인 집단 농장이 만들어졌다. 고려인의 귀환은 모든 권리의 제약이 사라진 1953-1957년에 이루어졌다. 현재 우즈베키스탄에는 약 20만 명의 고려인이 살고 있다. 이들은 모두 우즈베키스탄을 자신들의 고향으로 여기고 있다.”

감독으로부터 사용 허가를 받음

리가이 감독은 우즈베키스탄 고려인을 독특하고 고유한 집단으로 묘사한다. 다양한 사회학 이론(시원주의(primordialism), 동화(assimilation), 통합(integration) 등)을 고려인들에게 적용할 수는 있지만, 그들은 어느 이론에도 완벽하게 들어맞지 않는다. 발레리 한(Valery Khan)이 설명한 바와 같이, ” 독립국가연합의 고려인들은 조상들의 문화를 많이 잃어버렸지만, 그들은 자신들만의 독특한 문화, 즉 유라시아 고려인 문화를 만들어냈다” (Khan 2007).

결론: 고려인 영화, 디아스포라 개념에 도전하다

‘디아스포라’는 국가 정체성, 이주, 그리고 강제 이동을 이해하고 연구하는 중요한 개념적 틀로 자리잡았다. 디아스포라 연구와 디아스포라 영화는 고국이라는 개념과 정체성 문제를 밀접하게 연관시키고 있다. 그러나 최근 들어 고국 신화에 대한 언급은 점차 줄어들고 있다. 디아스포라 정체성은 고국에 대한 집착보다는 이주와 정착, 새로운 ‘고향’을 만들어가는 경험에서 형성되기 때문에(Soldavini 2010), 고려인과 같은 일부 소수 민족 공동체는 엄격한 기준 디아스포라, 특히 이상적인 조국 개념을 중심으로 한 디아스포라의 정의를 충족시키지 못한다. 어려움을 겪었음에도 불구하고, 고려인들은 소련 시민으로서의 정체성에 높은 가치를 두고, 소련 사회에 통합되는 데 성공했다. 이러한 사례에서, 디아스포라 영화는 정체성 변화의 복잡성을 묘사하고, (비)소속감을 전달하며, 소수 민족에 대한 인식을 확산시키는 중요한 역할을 한다. 조상의 고향이나 역사적 고국이라는 개념은 기억이나 강렬한 감정을 불러일으키는 힘이 있지만, 우즈베키스탄 고려인 감독들은 복합적인 정체성을 묘사함으로써 이상화된 조국에 대한 그리움을 중심으로 하는 디아스포라 영화의 본질에 도전하고 있다.

저자 소개

Olga Khan (helgafrey@naver.com)은

서울대학교 아시아연구소의 방문학자이며, 중앙대학교에서 영화학 박사 학위를 받았다. 그녀의 주요 연구 관심사는 현대 우즈베키스탄 영화, 여성 이미지, 그리고 문화 인류학이다. 2023년부터는 중앙유라시아연구협회(CESS)의 이사를 역임하고 있다.

참고문헌

- De Man, Alexander. 2023. “Reframing Diaspora Cinema: Towards a Theoretical Framework.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media 25, 24-39.

- Khan, Valeriy. 2007. “Корейская Диаспора СНГ и Корея [Korean Diaspora of CIS and Korea].” International Scientific Conference “한국과 우크라이나 그리고 CIS 국가간 문화의 대화.” Kyiv. July.

- ____________. 2011. “중앙아시아 고려인의 적응 및 사회적 지위, 그리고 성공.” 제1차 다문화와 디아스포라 국제 저명학자 초청강연. 경북대학교. 2011년 10월

- Oh, Chong Jin. 2006. “Ahıska Turks and Koreans in Post-Soviet Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan: The Making of Diaspora Identity and Culture.” Ph. D. Diss., Bilkent University.

- Prime, Rebecca. 2016. Cinematic Homecomings: Exile and Return in Transnational Cinema. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Sim, Ji Eun. 2019. “Film Hanaan (2011): Korea and Uzbekistan Seen from a Margin.” Journal of Eurasian Studies 10(1), 98-105.

- Soldavini, Irene. 2010. “Identity in Vietnamese Diasporic Cinema.” Ph. D. Diss., SOAS University of London.

- Son, Hijoo. 2012. “Paradox of Diasporic Art from “There”: Antidote to Master Narrative of the Nation?” The Journal of Korean Studies 17(1), 153–199.

- Tayturova, Elizaveta. 2023. “Корё-сарам: когда и как на просторах СССР сформировалась большая корейская диаспора [Koryo-saram: When and How the Large Korean Diaspora Was Formed in the USSR].” Vokrug Sveta. https://www.vokrugsveta.ru/articles/koryo-saram-kogda-i-kak-na-prostorakh-sssr-sformirovalas-bolshaya-koreiskaya-diaspora-id872862/ (Accessed 08. 09. 2024)

- Yoo, Jungmin. 2022. “The Lost Heritage of Koryoin: Citizen or Outcast?” Global Journal of Human-Social Science 22(C5), 37–45.

Identity and Belonging in Films of Uzbekistani Koryo-saram

Abstract. The Koryo-saram are diasporan Koreans from the former USSR who, due to various historical circumstances, relocated to the Russian Far East from the peninsula in the second half of the 19th century, followed by deportation to Central Asia under Stalin’s order, and have since resided in the post-Soviet space. Their assimilation process took place in a heterogeneous and ethnically unfamiliar setting, resulting in a synthesis of Korean, Russian, Soviet, Central Asian, and European cultures, along with the transformation and partial loss of the original ethnic culture. The hybrid and multilayered identity of Koryo-saram has been reflected in a variety of artistic genres, including literature, songs, paintings, and many others. Yet, their experiences have been underrepresented in cinema, particularly within the context of the broader Korean diaspora.

The Koryo-saram cinema represents a developing field and serves as a valuable source for investigating the culture of Uzbekistani Koreans; directors explicitly incorporate their own and others’ historical and cultural experiences into the film text. In this instance, diasporic cinema places greater emphasis on cultural aspects rather than ‘nation,’ while filmmakers reflect on what it means to be Koryo-saram in both a historical and contemporary context. In their works, directors exhibit a heterogeneous aesthetic and experience of living between two or more cultures as ethnic Koreans living in the multi-ethnic urban environment perceive themselves as part of many different cultures. In an attempt to introduce distinctive aspects of Uzbekistani Koreans’ lifestyles during the Soviet era and present time, filmmakers rebuild real-life events, stressing the importance of capturing their authentic heritage since everything connected to the original Koryo-saram culture is at risk of disappearing.

Keywords: Uzbekistan, Koryo-saram, cinema, diaspora, identity

Khan Olga (SNUAC)

In the former USSR, the process of assimilation of Koreans took place in a heterogeneous and polyethnic environment. Constant contact with representatives of different nationalities and exposure to various cultures resulted in the adoption of flexible psychological attitudes towards multiethnic surroundings, as well as adaptable models of their behavior. Decades-long residency in an ethnically alien environment inevitably leads to the transformation or loss of many components of the initial ethnic culture, which remain preserved in a homogeneous Korean environment. As a result, the difference between Koreans residing on the peninsula and those in the former USSR happened to be significant enough to support the emergence of a distinct ethnic group known as “Koryo-saram,” along with other similar ethnic groups such as Koreans in China, Japan, the USA, and elsewhere. The major difference, however, lies in the fact that the culture of Koryo-saram is a synthesis of Korean, Russian, Soviet, Central Asian, and European cultures (Khan 2011). This multilayered and complex identity of Central Asian Koreans has been reflected in various forms of art, including literature, songs, and paintings. Yet, the experiences of migrants belonging to minority communities have been rarely documented in films, particularly within the context of the broader Korean diaspora. In comparison to the number of documentaries and short videos produced by filmmakers, historians, and bloggers from South Korea, the USA, Canada, Russia, and Central Asia, there are relatively few features and short films since the cinema of Koryo-saram has historically fallen behind other creative forms in terms of time, quantity of creators, and works.

The cinema of Koryo-saram can be seen as a new phenomenon, with the first Uzbekistani Korean filmmakers appearing only after 2010—marked by the notable premier of Hanaan directed by Ruslan Pak—and it took a further decade for other directors to produce new works. Unlike numerous documentaries focusing on the deportation topic, emerging directors explore and evoke deep reflections on “what it means to be Koryo-saram” in a contemporary setting. As diaspora filmmakers are often celebrated as “agents of hybridity” (De Man 2023), ethnic Koreans exhibit heterogeneous aesthetics and employ narrative strategies in their films to communicate their cultural belonging and distinctiveness; their geopolitical trajectory and social identity play a significant role in influencing the aesthetics and addressing issues related to questions of origins, movement, and relocation. When it comes to cinema’s efficiency in delivering complex identities, displaying traditions, language, and heritage, diasporic artists are “especially able to captivate and fascinate the viewing audience by articulating the complicated ideas and difficult-to-describe conditions of living in diaspora” (Son 2012).

Hanaan (2011) by Ruslan Pak

Ruslan Pak, the descendant of the 4th generation of Koryo-saram, made his debut at international film festivals with a feature project Hanaan, which raised the subject of self-identity by introducing viewers to Uzbekistani Koreans, a lesser-known ethnic group. The plot revolves around Stas (played by Stanislav Tyan), an ethnic Korean who was born in Uzbekistan during the Soviet era, and delves into his psychological struggle and relentless pursuit of “the ideal” while coping with a pervasive sense of loss. The film genre can be classified as ‘neochernukha’ due to the permeating sense of hopelessness and aimlessness that is emblematic of the 1990s; post-Soviet Tashkent is represented by filthy apartments and run-down villas, where four friends—Stas, Shin, Kosoy (all ethnic Koreans) and Said (who looks like Caucasian)—spend their time by trying drugs and entangling in gang rivalries. All of them attempt to escape from their dismal existence: Shin goes to Korea, while Stas and the rest of the friends seek solace by resorting to drug use. However, once young men start experimenting with drugs, they embark on a trajectory that inevitably leads to the complete loss of everything they value, including their own lives.

Hanaan, like other films made by immigrants, explores the theme of identity – a major concept in diasporic films tied to the arduous quest for a sense of belonging that arises from dislocation and complicated feelings towards the notion of “historical motherland.” Shin, who earlier relocated to Korea, advises Stas to explore the possibility of a better life there, however, Stas’s reaction is ambiguous. “What does Korea have that we don’t have here?” asks Stas. “Sea,” answers Shin. Both Shin’s and Stas’s skepticism stems from the fact that the intensity of attachment between diaspora individuals and their homelands varies and depends upon their temporal and spatial proximity (Oh 2006), however, young men do not express a strong connection to their ancestral motherland due to historical unfoldings [1]. Hanaan suggests that not every immigrant holds great hope for their ancestral countries, since the “idea of centering on the ideal homeland marginalizes the importance of relationships and linkages formed by the diasporic conditions” (Soldavini 2010). Moreover, by showing how multiculturalism is deeply embedded into Stas and his companions’ daily routine and transmitted through elements like bilingualism, multi-national connections, and mixed cuisine, the film undermines diasporic “alleged essence or purity” (De Man, 2023).

Eventually, Stas goes to South Korea, only to discover that his friend’s prosperity is linked to drug dealing. Hanaan concludes with an open ending – in closing sequences, Stas is sitting alone by the sea, which represents the Promised Land; his further fate is unknown. Hanaan’s uncertain finale addresses the gap between the “unspoken” nostalgia for the mythical homeland and the reality of return, implying that ethnic Koreans who migrate to Korea, often find themselves continuing to “wander” even in their ancestral home, realizing the fact that this country cannot be their final destination (Sim 2019). The last minutes of the film make it clear that ‘Hanaan’ is not a forgotten homeland, and the “home” the hero longs for is inevitably located neither in the homeland nor the host country, but in the ongoing journey to some elusive “elsewhere” (Prime 2016).

When Poppies Bloom (2019) by Rita Pak

It is imperative to acknowledge that Koryo-saram cinema has not yet reached its highest point, representing a developing field where filmmakers are experimenting with self-expression within the framework of visual culture. However, analysis of diasporic art, including films, “brings together the voices of overseas Koreans on multiple levels in reading art, incorporating both the unevenness of “high” and “low” art practices” (Son 2012). Although Rita Pak’s When Poppies Bloom might not be considered a highly artistic work, it provides a valuable source for exploring Koryo-saram’s identity by delving into the lives and mindset of Koreans residing in Uzbekistan. It tells a story of success, picturing Roma (played by Vadim Kim and Vladimir Yugay)—a boy abandoned by his parents and raised by his grandparents on a Korean collective farm—who grows into a successful public employee. The entire film covers the life of a hero, starting from his early years and continuing into maturity as he navigates through various challenges and personal hardships.

Contemporary discourse designates kolkhozes as a unique phenomenon known as “Korean collective farm” and “space of memories.” The majority of the story takes place in kolkhoz, illuminating distinctive aspects of Uzbekistani Koreans’ living conditions during the Soviet era and featuring authentic elements such as Korean threshing machine (pai) and other attributes intrinsic to the bygone era. Nostalgia played a significant role in recreating the past – the director meticulously reanimates an in-depth portrayal of Koryo-saram’s life (byt), based on the experiences of an older generation, by staging anniversaries, Hwatu games, rice cake making, hangaby celebration, and other activities that recreate photographic verisimilitude and carry a nostalgic appeal. Within the context of the Soviet “merging of nationalities” policy, leading to ethnic Koreans’ downplay of their distinctive culture and identity, the film portrays Roma’s steady growth as both an individual and a member of the Korean community in a foreign cultural setting. When Poppies Bloom chronicles Roma’s life from childhood, encompassing his pioneering years, schooldays, service in the Navy, and work at the factory, proving that “Korean diasporas developed a modus vivendi of adaptation to the harsh circumstances of life in exile and consequent integration into a Russian/Russified society in a relatively short period of time” (Oh 2006). In this case, diasporic cinema focuses more on ‘cultural’ aspects rather than ‘nation,’ providing an extensive understanding of the historical and contemporary experiences of being a Koryo-saram. When Roma gets older, he is shown working at the factory within the urban scenery, while his grandparents are still residing in kolkhoz; this way the film illustrates the simultaneous coexistence of two Soviet Korean lifestyles – that of those who remained on Korean collective farms and that of those who moved to the city once the restriction on leaving the deportation area was lifted. Roma’s attire and haircuts also embody the essence of a certain decade, incorporating elements of Soviet fashion and lifestyle that differ from his initial ethnic heritage, but at the same time, his adherence to Korean traditions—through performing traditional bows at the cemetery or consuming Korean food—indicate his cultural linkage to the ancestral home.

The authors of When Poppies Bloom re-imagine the conception of identity by filming certain episodes entirely in Koryo-mal [2] – a language consistently spoken by older generations of ethnic Koreans, despite their proficiency in Russian. Larisa Ligay, who portrayed Roma’s grandmother, noted that during the 1970s, Koryo-saram experienced feelings of shame owing to their connection to collective farms and ability to speak Koryo-mal. On the contrary, When Poppies Bloom through the reenactment of several scenes in Koryo-mal—previously marginalized but currently being preserved—aimed to achieve a more authentic effect. In light of this, the shifting dynamic of Koryo-saram’s self-perception is interesting, as throughout the Perestroika period Soviet Koreans developed a strong sense of Korean identity and displayed a keen interest in embracing original Korean culture. However with time, they began to evaluate identity and belonging issues more critically; the feeling of inferiority that ethnic Koreans experienced in the 1970s and 1990s has since evolved into a sense of pride, while their “otherness” allowed Koryo-saram to identify themselves as a non-mononational group and part of the world’s global cultural tradition (Khan 2007).

The Choir (2019) and Pebbles (2023) by Larisa Ligay

The Choir was produced within the international laboratory of the documentary film “European Union Focus Cine Lab” and explores the theme of a “disappearing world.” According to director Larisa Ligay, “Both, The Choir and Pebbles, are focusing on the elderly generation of Koryo-saram. It is a particular group of individuals who once resided in collective farms and spoke koryo-mal, and to me, they represent the so-called disappearing world.”

The Choir seamlessly blends Korean, Russian, and Uzbek ethnic components, reflecting the diverse cultural identities of Koreans residing in a multi-ethnic setting. Ligay meditates on the experience of living between two or more cultures by documenting the choir members rehearsing Soviet songs or participating in a jovial feast featuring Russian and Uzbek meals, all the way conversing in both Russian and Koryo-mal. But following the rehearsal and feast sequences—filled with attributes of Uzbek and Russian cultures—the camera cuts to an image of women changing from their everyday clothes into traditional Korean hanboks, getting ready to take the stage. Choristers’ pre-performance preparations are accompanied by the soft humming of the Korean song that engulfs the space with a palpable ‘collective cultural memory.’ The documentary ends with close-ups of choir members and video footage of singing ensembles from different regions performing “Arirang” on a grand stage. Contrary to widespread opinion, “Arirang” in The Choir does not epitomize longing for an ancestral country but rather reflects the decline of the original Koryo-saram culture and its final remaining members.

Ligay expands upon the motif of the disappearing generation in her next work Pebbles. The plot delves into the slow tempo of an old man’s life (played by Vyacheslav Kim), who lives in kolkhoz and fancies a woman from a local Korean choir. Upon the unexpected death of the woman, the film not only depicts the unfortunate turn of events but introduces the funerary culture of Uzbekistani Koreans that has evolved over time as a fusion of different practices. In this instance, the Russian funeral orchestra, mourners wailing and bowing before the memorial table in the cemetery, and the ceremonial usage of white headscarves serve as visible signs of ethnic Koreans’ mixed identity. Through setting up cultural arrangements of Koryo-saram within the Uzbek landscape, Ligay not only builds a space of reminiscence and connection with ancestral land but also exhibits diasporic communities’ shared sense of identification with the country of their ethnic origin and the country they live in. After performing ritual bows, the protagonist picks a pebble from the grave and places it in a box, alongside other similar pebbles, as a tribute to the deceased people he used to know. At the end of the film, the director provides textual information on the historical background of Koryo-saram on-screen:

“In 1937, about 75,000 Koreans were forcibly deported from the southern regions of the Far East to Uzbekistan. The resettled Korean people had the status of administratively expelled. They were limited in their rights and could not move outside of Central Asia. They were placed on the virgin lands of the Tashkent region, the hunger steppe in the lower reaches of the Amu Darya and on the shores of the Aral Sea. Settlers joined 222 collective farms, and additional 50 Korean collective farms were created. The rehabilitation of Koreans took place in 1953-1957 when all restrictions on rights were lifted. Today, about 200, 000 Koreans live in Uzbekistan. Each of them considers Uzbekistan their homeland.”

Thus, Ligay communicates her central premise regarding Uzbekistani Koreans as a distinct and unique group – although multiple sociological theories (primordialism, assimilation, integration, etc.) can be applied to Koryo-saram, they do not entirely fall into any of them. As specified by V. Khan, “Koreans of the CIS have lost much of the culture of their forbears. But, on the other hand, they have created their own unique culture, the Eurasian Korean culture” (Khan 2007).

Conclusion

‘Diaspora’ has become a prominent conceptual framework for generating understanding and knowledge concerning nationhood, migration, and displacement. Diaspora studies, as well as diasporic cinema, closely link the idea of homeland and identity issues. However, in recent times references to the myth of the homeland have been reduced in number. Certain minority communities, like Koryo-saram, fail to meet the strict criteria of the diaspora—particularly those centered around the concept of an ideal homeland—since diasporic identities are formed out of the experiences of displacement, settlement, and building a new “home” in their host country rather than having a fixation with their homeland (Soldavini 2010). Despite facing difficulties, Koryo-saram succeeded in integrating into Soviet society, placing a high value on their identity as Soviet citizens. In this case, diasporic cinema plays an important role in portraying the complexity of identity transformation, conveying the sense of (un)belonging, and increasing awareness about ethnic minorities. The idea of an ancestral homeland/historical motherland has the power to evoke memories and intense emotions, however, Uzbekistani Korean directors through the depiction of hybrid identities challenge the very nature of diasporic cinema tied to a sense of longing toward an idealized homeland.

Author Introduction

Olga Khan (helgafrey@naver.com) is

a visiting fellow at Seoul National University Asia Center. She obtained a PhD in Film Studies at Chung-Ang University. Her main research focus is modern Uzbek cinema, female images, and cultural anthropology. Since 2023, she has served as CESS (Central Eurasian Studies Society) board member.

Notes

[1] Until 1953, Koreans were prohibited from traveling outside the deportation regions, but the exemptions in the 1950s provided Koreans with the chance to relocate from the countryside to urban areas in pursuit of education and alternative professional development opportunities. Although some managed to return to the Far East, Soviet Koreans lost their connection with their land of origin – the deportation had a profound impact on their culture and way of life (Tayturova, 2023).

[2] Koryo-mal stems from the pre-altered language spoken during Joseon-era Korea – when Korea was united (Yoo 2022).

[i] 1953년까지 고려인들은 강제이주지 밖으로 나갈 수 없었다. 1950년대 금지가 해제된 이후 고려인들은 교육이나 다른 전문적 기술을 배울 기회를 얻기 위해 농촌에서 도시로 이주했다. 일부 고려인은 돌아갈 수 있었지만 대부분은 한국과 관계가 단절되었다. 강제이주는 고려인의 문화와 생활 방식에 큰 충격을 남겼다(Tayturova, 2023).

[ii] 고려말은 한반도가 분단되어 언어가 달라지기 전 조선시대에 쓰이던 한국어에서 갈라져 나온 언어다.