무함마드 이르판(Muhammad Irfan)

음악과 저항은 하나다

역사적으로 음악과 저항은 저항 운동에서 한 몸처럼 서로 긴밀히 연결되어 있었다. 물론 음악은 다른 예술과 마찬가지로 저항 운동에 직접 영향을 주지는 않는다. 음악은 적을 제압하는 총알도 폭탄도 아니다. 그러나 음악은 횃불처럼 정신을 일깨우며, 사람들은 음악을 통해 저항 운동을 인식하고 더 많이 참여하게 된다. 로빈 발리저(Robin Balliger)는 1999년에 쓴 『대중 음악으로 본 사회(Understanding Society through Popular Music)』에서 음악과 정치는 분명하게 서로 얽혀 있다고 말했다. 음악은 국가나 경제 체제와 같은 지배 구조에 맞서 싸우는 수단이 되기도 하며, 민족 의식이나 애국심을 담은 노래는 이미 존재하는 가치를 더욱 강화하기도 한다(Kotarba·Vanini, 2008; 73에서 재인용). 이러한 경향은 팔레스타인 민중의 투쟁에서도 뚜렷이 찾아볼 수 있다.

1940년대 후반 이스라엘 시온주의자들의 지배 아래에 놓인 이래로 팔레스타인인들은 정치적, 외교적 수단과 물리적 수단 등 다양한 방식으로 저항했다. 다양한 저항 수단 가운데 예술이, 그중에서도 음악이 있었다.

팔레스타인 저항 음악은 한 장르에만 국한되지 않으며, 민요, 군사 행진곡, 고전 음악, 도시 힙합(McDonald, 2013, p. 6)을 포괄한다. 맥도널드(David A. McDonald)의 표현을 빌리자면 팔레스타인 저항 음악은 “어떤 장르든 의식적으로 음악을 팔레스타인 민족자결권 성취를 위해 이용하는 것”이라고 할 수 있다(McDonald, 2013: 5-6). 실제로 팔레스타인에서는 결혼식에서도 저항을 외치는 노래를 들을 수 있고, 사람들은 시위에서 결혼식 노래를 부르기도 한다(McDonald, 2013: 4).

이 글에서는 팔레스타인 힙합에 주목한다. 팔레스타인 힙합의 역사는 적어도 1998년까지 거슬러 올라간다. 바로 이 해에 이스라엘이 점령한 팔레스타인 지역에 있는 마을인 리드(Lyd) 출신의 아랍 청년 타메르 나파르(Tamer Nafar)가 “Untouchable”이라는 이름으로 데뷔했다(Batterridge-Moes, 2021). 1년 뒤인 1999년 나파르는 형제인 수헬 나파르(Suhell Nafar), 친구 마흐무드 즈레레(Mahmood Jrere)와 함께 팔레스타인 최초의 힙합 그룹을 결성했고, 그룹명을 아랍어로 피를 의미하는 ‘DAM’이라고 지었다. DAM은 창작 활동을 시작하며 노래를 녹음해 소셜미디어를 통해 음악을 배포했으며, 주로 마이스페이스(MySpace)에 음악을 올렸다. DAM의 싱글 “누가 테러리스트지?(Meen Erhabi?)”는 특히 폭발적인 인기를 끌었다(Batterridge-Moes, 2021). DAM이 유일한 팔레스타인 힙합 그룹이 아니다. 팔레스타인 점령지의 MWR, 서안지구의 라말라 언더그라운드(Ramallah Underground), 체크포인트 303(Checkpoint 303), 보이쿠트(Boikutt), 가자지구의 PR (Palestine Rapperz) 등이 대표적인 팔레스타인의 힙합 그룹이다.

출처: DAM Facebook 페이지

“누가 테러리스트지?(Meen Erhabi?)”

팔레스타인, 노래와 시로 이스라엘에 저항하다

음악과 시는 아랍인들, 특히 팔레스타인인들의 삶에서 떼어놓을 수 없는 요소로서 사람들의 전통 속에 살아 있으며 구어체 아랍어로 표현되고 즉흥적으로 나타난다. 음악과 시는 서로 밀접하게 연결되어 있다. 전문 시인들은 결혼식, 축제나 사람들이 즐겁게 모이는 행사에서 시를 낭송한다(Darweish·Robertson, 2021). 푸라니(2013)는 아랍인들 사이에서 시가 소설, 신문 기사, 연설, 연극과 같은 다른 장르보다 중요하게 여겨지는 이유는 고대부터 아랍인들이 시를 표현 수단으로 사용했기 때문이라고 설명한다(Furani, 2013: 81).

‘노래와 하나가 된 시’는 1948년 팔레스타인 지역에서 이스라엘의 군정이 시작된 이후 더욱 중요해졌다. 시는 주로 이스라엘 군정에 대한 저항, 자유, 1948년 1차 중동전쟁의 패배로 팔레스타인인들이 겪은 나크바(대재앙Nakba)에 대한 반응을 다루었다. 푸라니에 따르면 이 시기에 다른 대중매체가 이스라엘 법에 따라 검열을 받는 상황에서 시는 은밀한 저항을 위한 ‘언어의 지하조직’이었다. 상대적으로 쉽게 전달되고 낭송되고 암기되고 퍼져나갈 수 있었기 때문이다(Furani, 2013: 81). 마르완 다르위시(Marwan Darweish)와 크레이그 로버트슨(Craig Robertson)은 마하 나사르(Maha Nassar, 2017)를 인용해 이스라엘 군정 시기에 팔레스타인인들이 쓴 글, 특히 시에서 ‘이스라엘 정책과 그 기저에 놓인 시온주의 논리에 대한 저항을 팔레스타인과 아랍뿐만 아니라 전 세계적인 탈식민화 저항이라는 큰 맥락과 연결하는 경향이 나타난다’고 주장한다. 이러한 경향은 이 시기 팔레스타인 시인들이 쓴 작품에서 찾아볼 수 있다.

다르위시와 로버트슨이 제시하는 대표적인 예는 가수 겸 시인이었던 바드리야 유니스(Badriyya Younis, 1915년 출생, 2001년 사망)와 아우니 스바이트(Awni Sbait, 1929년 출생, 2008년 사망)다. 무슬림 여성이었던 바드리야는 사랑에 관한 노래인 “군대에서 멀리 도망쳐라(ḥayyid ʿan il-jhaishi yā ghbaishī’)”로 유명하다. 이 노래에서 바드리야는 절대로 항복하지 않고 용감히 싸웠던 연인을 자랑스러워는 여인의 감정을 들려준다. 한편 마론파 기독교도이자 아랍인인 아우니는 사회적, 정치적 문제와 고향에 대한 애착과 사랑을 노래했다. 아우니의 고향으로 1948년 이스라엘이 점령한 마을인 이그리스(Igrith)는 아우니의 시에서 중심적인 위치를 차지한다. 1976년에 지은 노래인 “복수”에서 아우니는 자존심과 존엄성을 지키며 살아남으려는 투쟁과 억압에 굴복하지 않으려는 의지를 노래한다. 이러한 메시지는 노래의 첫 가사에서부터 명백하게 나타난다. “나는 자유로운 이그리스에서 태어났다!”

아우니는 또한 국제주의자로 알려져 있고 공산주의 사상과 가까웠으며, 일부 작품에서는 노동자와 농민, 국제적 연대에 관해 다루었다. 다르위시와 로버트슨은 “아우니는 팔레스타인의 무슬림, 기독교도, 유대인 관계의 미래에 관해 그려냈고, 노래를 통해 이스라엘 지도자들에게 ‘팽창 정책과 인종주의를 버리고 아흐마드와 하임과 한나가 평화롭게 살게 해라!’로 외쳤다(Sbait, 1976a, 1976b: 23).” 푸라니에 따르면 1967년 3차 중동전쟁이 끝난 후 문학평론가이자 소설가인 갓산 카나파니(Ghassan Kanafani)는 이러한 작품을 ‘저항 문학(adab al-muqawama)’으로 분류했다(Furani, 2013: 86).

“목소리를 내려면 용기가 필요할 때”

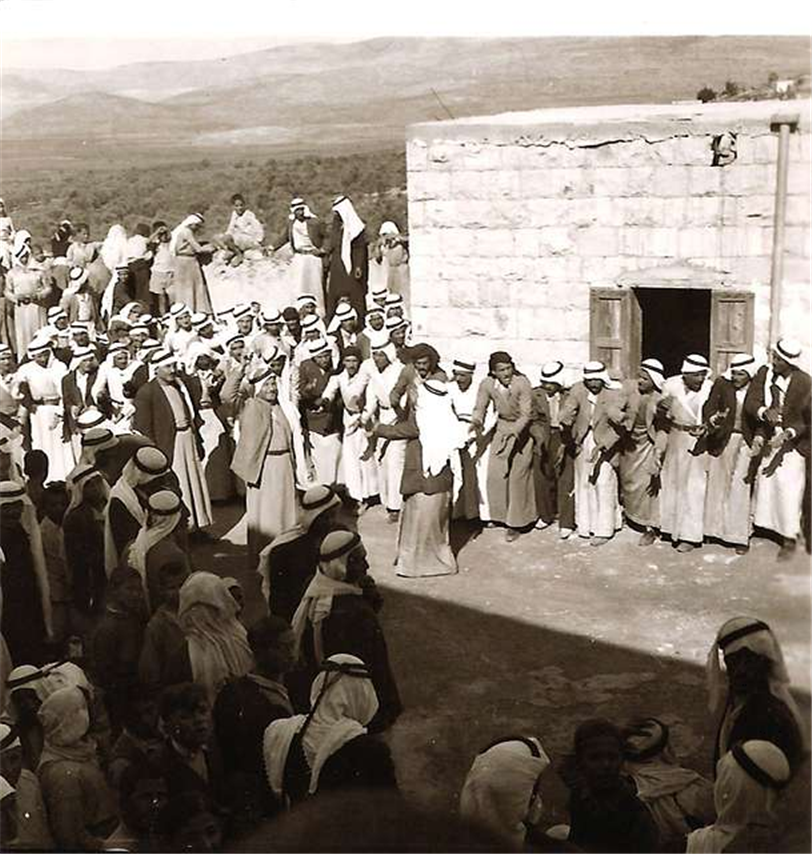

노래로 불리는 시는 또한 결혼식과도 떼어 놓을 수 없다. 위에서 언급되었듯이 맥도날드에 따르면 사람들은 결혼식에서 저항을 외치는 노래를, 시위 현장에서 결혼 노래를 부르기도 한다. 이러한 모습은 팔레스타인 아랍인 공동체에서 결혼식이 중요한 사회적 행사라는 점과 밀접하게 관련되어 있다. 결혼식, 특히 도시와 마을 주요 광장(바이다르, Bydar)에서 열리는 결혼식은 중요한 사회적 행사다. 많은 사람이 모이는 행사인 결혼식은 당연하게도 떠들썩하게 열리는 축제며, 시를 노래하는 가수들은 잔치 분위기를 띄우는 역할을 했다.

출처: https://www.pikiwiki.org.il/image/view/11009

팔레스타인에서 바드리야와 아우니와 같은 가수들은 결혼식을 땅에 대한 애착을 드러내고 이스라엘 군정에 대한 반감을 표현하는 자리로 삼았으며, 결혼식에서 아랍인의 민족적 연대와 팔레스타인 민족의식과 정체성을 고취하는 노래를 불렀다. 다른 평범한 가수들과 달리 이들은 이스라엘 정권과 공공연하게 협력하기를 거부했다(Darweish·Robertson, 2021). 푸라니는 다음과 같이 설명한다:

결혼식과 같이 전통적이고 익숙한 행사를 통해 사람들은 각자 가진 두려움과 나약함을 극복하고 함께 모일 수 있었으며 새로운 것이 세상에 등장할 수 있었다. 생존을 위한 집단적 투쟁에서 팔레스타인 시인들은 목소리를 내기를 갈망하고 언어만이 줄 수 있는 피난처를 찾는 사람들을 향해 노래했다. 시인 한나 이브라힘이 말한 대로 “목소리를 내려면 용기를 내야 할 때” 사람들이 두려움에 맞서 용기를 낼 수 있도록 했다. 팔레스타인 시인들은 저항적인 “노래”로 억압에 맞섰다. 아마 가장 유명한 사례는 1964년 젊은 마흐무드 다르위시(Mahmood Darwish)가 발표한 시일 것이다. 다르위시의 시는 이후 노래로 만들어지기도 했다(Furani, 2013: 89).

조셉 마사드(Massad, 2003)는 시온주의 식민화에 맞서는 팔레스타인 노래를 10년 단위로 구분한다. 형식, 장르, 주제는 시대에 따라 달라졌다. 1950년대에는 트랜지스터 라디오가 대중화된 덕분에 노래도 퍼져나갈 수 있었고, 1960년대에는 텔레비전을 통해 확산되었다. 이 시기 노래에는 이집트의 가말 압둘 나세르(Gamal Abdul Nasser) 대통령이 이끈 혁명에 대한 신뢰가 담겨 있다. 1952년 압둘 나세르가 혁명을 일으켰을 때 이집트인뿐만 아니라 다른 아랍 국가의 국민도 기뻐했고, 팔레스타인과 알제리를 해방할 것이라고 기대했졌다. 하지만 1970년대의 노래, 적어도 1967년 전쟁에서 패배한 직후의 노래는 과거와 달라졌다. 1970년대에 들어 카세트테이프를 통해 유통된 노래에서는 패배가 남긴 절망감이나 당시에 막 성장하기 시작한 팔레스타인 게릴라 운동에 거는 기대가 나타나기 시작했다(Massad, 2003: 21).

시온주의 식민 지배에 맞선 팔레스타인인의 투쟁은 국경을 초월해 노래로 만들어졌다. 1948년 나크바 이후 팔레스타인에 관한 노래는 아랍 각지로 퍼져나갔다. 레바논의 나자 살람(Najah Salam), 시리아의 파리드 알아트라슈(Farid al-Atrash), 이집트의 무함마드 압둘 와합(Muhammad Abd al-Wahhab) 모두 팔레스타인에 관한 노래를 불렀다. 1948년 작곡되고 1949년 공개된 압둘 와합의 노래 “필라스틴(Filastin)”은 큰 인기를 끌었다.

인티파다, 새로운 저항 음악의 출현

맥도날드에 따르면 많은 팔레스타인 뮤지션이 1987년 시작되어 1993년까지 이어진 팔레스타인 봉기, 즉 1차 인티파다(Intifada) 기간에 활동했다. 이 기간의 팔레스타인 음악은 두 부류로 나눌 수 있다. 바로 순교를 촉구하는 노래와 폭력과 이산(離散)의 경험과는 전혀 무관한 주제를 노래하는 초국적인 팝송이다(McDonald, 5). 1차 인티파다는 또한 1970년대 초반 서안지구의 민속유산축제가 부흥하는 계기가 되었고, 축제에서 민속 시인들을 팔레스타인 민족 문화와 관습의 상징으로 내세우던 방식도 다시 주목을 받았다(McDonald, 2013: 124)

이와 함께 언더그라운드 음악 문화도 팔레스타인 음악가들 사이에서 나타났다. 이들은 지하의 비밀 스튜디오에서 음악을 녹음해 인티파다 초반 몇 달 동안에 시위 현장에서 직접 음악을 배포했다. 이스라엘 식민정권의 탄압을 피하기 위해 팔레스타인 음악가들은 가명을 사용했다. 서안지구에서는 사바예 알인티파다(Sabaye al-Intifada, 인티파다의 청년들), 이브나 알빌라드(Ibna al-Bilad, 땅의 아들들), 알아말 알샤으비(al-‘Amal al-Sha’bi, 민족적 노력)과 같은 음악가나 그룹이 그 예다(McDonald, 2013: 125).

서안지구와 가자지구에서는 서로 다른 형태의 저항 음악이 등장했다. 서안지구에서 저항 음악은 세속적 민족주의나 마르크스주의에 따라 제국주의에 저항하는 제3세계 게릴라 운동의 영향을 받았다. 독립해서 활동하는 음악가뿐만 아니라 팔레스타인해방기구(PLO, Palestine Liberation Organization), 팔레스타인인민해방전선(PFLP, Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine) 등의 저항 조직과 관련된 음악가들도 새로운 형태의 음악을 선보였다. 서안지구의 저항 음악은 또한 전통적인 팔레스타인 민속 음악뿐만 아니라 서구 음악의 영향도 받았다.

한편 가자지구에서는 종교적으로 보수적인 수니파 이슬람주의 조직 하마스(Hamas)가 권력을 잡았고, 아나쉬드(anashid)라고 불리는 음악 장르가 서구식 음악보다 인기를 얻었다. 아나쉬드의 가사는 주로 쿠란이나 순나(예언자 무함마드의 언행을 기록한 책)에서 따왔다. 맥도날드에 따르면 하마스는 쿠란과 순나의 표현을 토대로 팔레스타인 해방에 대한 인식을 구성했고 신실한 무슬림들로 구성된 공동체인 움마(umma)가 팔레스타인 민족 공동체가 지향할 목적지가 되었다. 이를 위해 민족 공동체의 개념이 종교와 신앙의 테두리 안에서 다시 정의되었고 아나쉬드를 통해 표현되었다(McDonald, 2013: 128). 서안지구와 가자지구의 음악은 또한 표현 방식에서도 서로 다르다. 서안지구에서는 팔레스타인 민속 무용인 다브케(dabke)를 공연이나 행사에서 쉽게 볼 수 있는 반면, 가자지구의 하마스는 다브케를 종교적 율법에 위배되고 정숙하지 않은 것으로 보았다. 공공장소에서 춤을 추는 것은 남녀 모두가 있는 상황에 적합하지 않은 행위로 여겨졌다. 악기에 대한 관점도 달랐다. 하마스는 악기를 사용해 연주하는 것을 금지했다. 아나쉬드를 부를 때는 박자가 없는 리듬에 맞춰 불렀다. 다만 넓적한 북인 다파트(daffāt) 한두 개를 치면서 부르는 모습은 어렵지 않게 볼 수 있다(McDonald, 2013: 129).

출처: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Palestinian_Dabkeh.jpg

인티파다 시기의 음악은 최근 다시 인기를 끌기 시작했다. 2022년 영국에서 활동하는 팔레스타인 영화감독이자 배우인 모으민 스와이타트(Mo’min Swaitat)는 리아드 아와드(Riad Awwad)가 1987년 발매한 뒤 판매금지된 앨범인 “인티파다”를 발견했다. 스와이타트는 서안지구 제닌(Jenin)의 낡은 카세트테이프 가게에서 리아드의 앨범을 찾아내 다른 테이프 1만 개와 함께 사서 짐꾸러미 5개에 담아 런던으로 가지고 왔다. 가디언지와의 인터뷰에서 스와이타트는 리아드의 앨범을 발견한 것이 가장 특별한 경험이었다고 말했다. 밝은 노란색 테이프에는 아무런 설명도 없었고, ‘인티파다’라는 단어가 쓰인 스티커만 붙어 있었다(McKernan, 2022).

리아드 아와드, “인티파다”

스와이타트는 앨범을 여러 번 들으며 잃어버린 고향과 자유를 위한 투쟁을 그려내는 시적인 가사에 사로잡혔다. 곡 중간에 작곡가가 자기 이름을 리아드 아와드라고 말하기 전까지는 누가 앨범을 만들었는지도 몰랐다. 스와이타트는 팔레스타인에서 리아드의 가족을 찾아나선 뒤에야 리아드에 대해 더 많이 알 수 있었고, 유명한 작가이자 운동가이며 리아드의 누이인 하난도 만났다. 이미 70대에 접어든 하난에 따르면 리아드는 전기 기술자였으며 음악에 열정을 가지고 있었다. 인티파다가 시작된 첫 주에 리아드는 가족들을 모아 앨범 제작을 도와달라고 부탁했고, 당시 팔레스타인인의 노래를 앨범에 수록했다.

팔레스타인의 힙합 가수들은 무엇을 노래하는가?

힙합은 1990년대 중반 이전에는 팔레스타인에 존재하지 않았다. 팔레스타인 힙합은 아랍 전통 음악과 미국의 힙합 비트가 혼합되며 하위 음악 장르로서 등장했고 가수들은 아랍어, 영어, 심지어 히브리어로 가사를 썼다. 히브리어 가사로 쓰인 팔레스타인 노래는 팔레스타인인과 그들의 자손들이 리드나 하이파처럼 이스라엘이 점령한 땅에 살고 있는 상황과 결코 무관하지 않다. 리드의 DAM, 이그리스에서 태어나 하이파에서 자란 작곡가이자 활동가인 왈라 스바이트(Walaa Sbait)가 대표적인 예다. 영국에서 자란 여성 래퍼 샤디아 만수르(Shadia Mansour)처럼 힙합은 서구권에 살고 있는 팔레스타인 이민자와 이민 2세대도 즐기는 장르다. 수나이나 마이라(Sunaina Maira, 2008)는 이러한 모습을 팔레스타인 힙합에 대한 초국적(transnational) 관점이라고 정의한다. 정치 운동과 청년 문화는 국경을 넘어 서구권과 팔레스타인을 연결하며, 팔레스타인 힙합은 바로 이러한 배경 속에서 등장했다.

팔레스타인 힙합은 MTV를 통해 투팍 샤커(Tupac Shakur)와 같은 미국 힙합 아티스트들을 접하고 영향을 받았다. DAM의 마흐무드 즈레레에 따르면 투팍의 노래 “Holla if Ya Hear Me”는 거리에서 살아간다는 것이 무엇인지를 그려내 리드의 아랍 청년들 사이에서 인기를 끌었다. 청년들이 노래를 마치 자신들의 이야기처럼 느꼈기 때문이다. 마흐무드는 이렇게 말했다:

“우리는 주택단지에서 가난하게 살았다. 매일 범죄가 발생했고 경찰들은 우리를 쫓았다. 뮤직비디오에서도 똑같은 모습을 봤다. 가사 전체를 이해할 수는 없었지만, 그 고통과 투쟁이 무엇인지는 알 수 있었다.”

DAM은 초기 발표곡에서 자신들의 상황을 숨기지 않고 밝힌다. “여기서 태어났다(hwn ‘anuldt)”라는 곡에서 마흐무드는 이렇게 노래한다.

“내 소개를 하지, 나는 리드라는 곳에서 왔어

세상 범죄란 범죄는 다 거기에 있지

거기 사람들이 한 잘못이라고는 그 땅에 살고 있다는 것밖에 없는데”

과거 노래로 불린 시가 그러했듯이 힙합도 팔레스타인인으로서 뿌리와 정체성과 밀접하게 관련되어 있으며 팔레스타인의 투쟁과 역사를 말한다. 팔레스타인 힙합 음악가나 DJ가 다브케 민요나 우드 연주, 팔레스타인 시인들의 시, 정치인과 활동가들의 연설을 섞어 샘플을 만드는 것은 흔한 일이다.

DAM은 2006년 발매한 데뷔 앨범인 “헌사(Ihda)” 가장 앞부분에 가말 압둘 나세르의 연설을 실어 압둘 나세르의 혁명에 신뢰를 걸었던 1950년대 팔레스타인 음악가들을 떠올리게 한다. 오르(2011)가 보기에 이는 압둘 나세르의 연설에서 가져온 도입부에 여러 의미를 결합해 독특한 민족주의적 수사를 드러내기 위한 목적이다. 이스라엘에 사는 팔레스타인인으로서 DAM 멤버들은 압둘 나세르의 연설을 통해 팔레스타인인과 아랍의 연대를 표명하고 이스라엘을 당황하고 두렵게 만들었던 과거의 기억을 다시 일깨우는 것이다(Orr, 2011: 8).

힙합/일렉트로닉 뮤지션들로 구성된 체크포인트303 또한 “가자 해안 – 단조(Gaza Sea Minor)”라는 곡에서 갓산 카나파니와 호주 언론인 리처드 칼튼(Richard Carleton)의 인터뷰 음성을 사용했다. 인터뷰 음성은 잔잔한 우드 가락과 팔레스타인에 대한 이미지를 전달하기 위해 가자 해안가에서 녹음한 소리와 오버랩된다. 노래에는 1972년 카나파니가 모사드의 차량 폭탄 공격으로 사망했다는 뉴스 보도도 삽입되어 있으며, “죽을 때까지 싸운다!”라는 문장도 반복해서 들린다.

체크포인트303, “가자 해안 – 단조(Gaza Sea Minor)”

런던의 팔레스타인 힙합 뮤지션인 샤디아 만수르는 팔레스타인 매체인 사마르 미디어(SAMAR Media)와의 인터뷰에서 힙합을 통해 점령된 삶을 살아가는 경험을 이야기하고 저항 정신을 일깨우는 것 외에도 팔레스타인인이자 아랍인으로서 정체성을 일깨우는 것도 중요하다고 이야기했다. 샤디아는 자신을 “망명지의 팔레스타인인”으로 소개하고 자신의 노래에 삶의 경험이 반영되어 있다고 이야기한다. 샤디아는 누군가가 노래를 쓰거나 대의나 조국과 관련된 프로젝트를 할 때마다 항상 아랍 정체성 또는 팔레스타인 정체성으로 이어지는 다른 길이 나타났다고 말한다. 그리고 그녀가 믿기에 어디에든 팔레스타인인들이 존재하는 것 자체가 저항이다.

“미디어는 우리 민족을 왜곡하고 있습니다. 팔레스타인인만이 아니라 아랍인들 전체를요. 그렇기에 우리가 모든 것을 보존해야 합니다. 이것은 존재의 문제입니다.”

샤디아 만수르, “아랍 쿠피야”

따라서 샤디아는 노래를 통해 팔레스타인의 문화 유산에 다시 주목하고자 한다. “아랍 쿠피야(El-Kofeyye Arabeyye)”라는 노래에서 샤디아는 이렇게 썼다:

“나는 샤디아 만수르

쿠피야는 나의 정체성

내가 태어난 날부터

나는 이 사람들을 책임졌지

봐, 나는 동방과 서방 사이에서

두 언어 사이에서, 가난한 자와 부자들 사이에서 자랐고

양쪽 모두에도 살아봤어

나는 쿠피야

네가 어떻게 입든, 어디에 나를 버리든

나는 내 뿌리를 잃지 않지, 팔레스타인이라는 뿌리를

샤디아는 옷차림을 통해서도 자신의 정체성을 드러낸다. 항상 팔레스타인 전통 의복을 입고 공연해 자신이 팔레스타인이라는 정체성을 선언한다.

팔레스타인 청년들, 돌 대신 마이크를 들다

팔레스타인 힙합에는 팔레스타인인들의 저항을 이끈 음악의 역사가 응축되어 있다. 1950년대 시와 음악이 혼합된 형태로 나타난 저항 음악은 1980년대 후반부터 1990년대 초반 1차 인티파다 기간에 애국적 노래로 변화했다. 1970년대 미국 흑인 청년 문화에서 시작된 힙합은 팔레스타인 힙합 음악가들에게 영향을 주었고, 팔레스타인인들은 힙합을 통해 이스라엘의 지배 아래에 사는 자신들의 경험을 표현하기 시작했다.

미국 힙합은 인종주의와 흑인에 대한 차별을 비판했고, 팔레스타인 청년들은 미국의 힙합 문화를 이스라엘의 지배를 받으며 겪는 경험과 아랍인 소수자로 살며 마주하는 차별과 비슷하다고 여기고 받아들였다. 무엇보다도 시를 노래로 바꾸는 것은 팔레스타인의 오랜 전통이기도 했다.

힙합 DJ는 다양한 종류의 음악을 믹스해 비트를 만들고, 비트를 통해 다양한 음악을 한 곡이나 한 비트에 담아 아우른다. 이 덕분에 팔레스타인 힙합 그룹들은 다브케나 우드 연주와 같은 팔레스타인 민속 전통을 작곡에 활용할 수 있었다. DAM이나 체크포인트 303과 같은 힙합 뮤지션들은 시나 연설을 힙합 음악의 구조와 결합하기도 한다.

팔레스타인 힙합은 계속해서 발전하고 새롭게 탄생할 것이다. 최근에는 MC 압둘(본명은 압둘 라흐만 알샨티Abdul Rahman al-Shantti)이 두각을 드러냈다. 2008년 가자지구에서 태어난 이 소년은 2020년 가자의 학교에서 친구들과 랩을 하는 모습으로 센세이션을 일으켰다. MC 압둘은 아직 어리지만, 1990년대 후반 DAM이 했던 것처럼 랩을 부르는 뛰어난 능력을 갖춘 채 조상들로부터 시를 쓰는 능력을 이어받고자 한다. 다른 모든 팔레스타인 힙합 뮤지션과 마찬가지로 MC 압둘이 나중에 작곡한 노래에도 이스라엘의 맹렬한 공격 속에서 살아온 경험이 드러난다. 2021년에는 한 인터뷰에서 ”글을 쓸 때 내 펜에는 힘이 깃든다. 그럴 때는 멈출 수가 없다. 마이크는 내게 유일한 탈출구다“라고 말하기도 했다.

출처: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCDqQ8S7zCgraYPxCCkGO8KA

MC 압둘, “벽을 향해 외치다(Shouting At The Wall)”

서안지구 베들레헴의 힙합 그룹인 팔레스타인 스트리트(Palestine Street)는 청년들, 특히 난민캠프에 사는 청년들이 힙합을 통해 절망과 불안에 맞선다고 말한다. 청년들은 힙합으로 일상에 관해 솔직히 말하는 법을 배운다. 멤버인 헤파위(Hefawi)는 알자지라와 한 인터뷰에서 ”군인에게 돌을 던져 자신을 표현하고 절망을 드러낸다. 군인에게 돌을 던질 때 더 나은 삶을 요구하는 것이다. 힙합을 발견한 뒤에는 거리로 나와 돌을 던지는 에너지를 힙합에 쏟고 있다.“

팔레스타인 스트리트는 2013년부터 서안지구와 동예루살렘의 난민캠프에 사는 아이들에게 힙합을 가르치고 있다. 힙합의 힘을 믿기 때문에 아이들에게 분노와 좌절을 랩으로 표현하는 동시에 팔레스타인의 권리를 지키는 방법을 전하고자 한다. 팔레스타인에서 음악과 저항은 떼어놓을 수 없다. 지난 10년간 팔레스타인 저항 음악의 중심에는 힙합이 있었다.

저자소개

무함마드 이르판(Muhammad Irfan, irfanism90@gmail.com)은

국립양밍자오퉁대학교 석사과정생으로 독립음악과 하위문화와 관련된 청년 문화를 연구하고 있다. 저서 Bandung Pop Darlings: Catatan Dua Dekade Skena Indie Pop Bandung 1995-2015“(2019)에서 인도네시아 반둥 지역의 인디 음악을 다루었으며 영상 에세이로는 ”Numpang Gandeng: A Video Essay Explores The Indonesian Underground Music Scene in Taiwan” (2022)이 있다. 2023~2024년 개최된 타이페이 비엔날레에서 “Have You Ever Met Dao Ming Tse”라는 주제로 전시회에 참여했으며, 2024년 8월부터 10월에는 대만 타이페이에서 “Have You Ever Met Dao Ming Tse” for Taipei Biennial 2023-2024 in January and “Rocking Indonesia: A Cultural Legacy of The Rolling Stones in Bandung”라는 주제로 전시회를 개최했다.

참고문헌

- Abou-Chakra, Razan. 2021. “MC Abdul: Young Palestinian Rapper Drops His First Song.” CQ Middle East. https://www.gqmiddleeast.com/culture/young-palestinian-rapper-mc-abdul-drops-his-first-official-song (검색일: 2024. 9. 9).

- Ashly, Jaclynn. 2017. “Palestinian hip-hop group uses music as a weapon.” Al-Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2017/1/20/palestinian-hip-hop-group-uses-music-as-a-weapon (검색일: 2024. 9. 9).

- Darwiesh, Marwan and Craig Robertson. 2021. “Palestinian Poet-Singers: Celebration Under Israel’s Military Rule 1948–1966.” Alternatives 46(2): 27-46.

- El Roubi, Nadine. 2022. “Music of the First Palestinian Intifada Re-Discovered & Restored.” Scene Noise. https://scenenoise.com/News/Music-of-the-First-Palestinian-Intifada-Re-Discovered-Restored (검색일: 2024. 9. 9).

- Furani, K. 2022. “Dangerous Weddings: Palestinia Poetry Festivals During Israel’s First Military Rule”. The Arab Studies Journal 21(1): 79-100.

- Kotarba, J., & Vannini, P. (eds) 2008. Understanding Society through Popular Music. London and New York: Routledge.

- Massad, J. 2003. “Liberating Songs: Palestine Put to Music”. Journal of Palestine Studies, 32(3): 21–38.

- Maira, Sunaina. 2008. ““We Ain’t Missing”: Palestinian Hip Hop—A Transnational Youth Movement.” CR: The New Centennial Review 8(2): 161–192.

- McDonald, D. A. 2013. My Voice is My Weapon: Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics of Palestinian Resistance. Durham: Duke University Press.

- McKernan, B. 2022. “‘A journey through the past’: Lost music of the Palestinian uprising is restored.” The Guardian.

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jan/12/a-journey-through-the-past-lost-music-of-the-palestinian-uprising-is-restored (검색일: 2024. 9. 9).

- Orr, Y. 2011. “Legitimating Narratives in Rhyme: Hip-Hop and National Identity in Israel and Palestine.” M. A. Thesis., The University of Pennsylvania

Hip Hop and People’s Resistance in Palesitne: From Sung Poetry to the Spirit of Intifada

<Abstract>

This article explores the hip-hop music scene in Palestine and its effect on the consciousness of the people’s struggle there, especially among the youth. Hip-hop in Palestine was started by DAM, a Lyd-based hip-hop trio founded in 1999. They often express their feelings as Palestinian Arabs living under the Israeli occupation regime through their lyrics and rhymes. However, Palestinian hip-hop is not only about DAM. The scene appeared and developed gradually, becoming a torch that ignited youth awareness of the Palestinian struggle. It has spread the movement on the cultural scene not only in Palestine but also globally. Moreover, Palestinian hip-hop is not limited to musicians based in Palestine or occupied Palestine; it is also represented by the Palestinian diaspora.

Music and resistance in several historical struggles have become two sides of the same coin, deeply interconnected. Music, like any other art form, does not directly influence resistance movements. It is not a bullet that can immediately paralyze the enemy, nor is it a bomb. However, music can be a torch that ignites the spirit and inspires people to become conscious of or get involved in struggle movements.

As Balliger (1999) is quoted by Kotarba and Vannini in Understanding Society through Popular Music, “music and politics are explicitly mixed.” Music can be a form of resistance against dominant institutions such as the state or the economic system, or it can support existing values, such as in national or patriotic songs (Kotarba & Vannini, 2008, p. 73). This tendency is also evident in the Palestinian people’s struggle.

Since the late 1940s, when the area was occupied by Israeli Zionists, Palestinians have employed various forms of resistance: political, diplomatic, and physical. Among these forms, the arts, including music, have also played a role.

Music defined as resistance music in Palestine is not confined to a single genre. It can be found in rural folk songs, militarized marches, classical art music, and urban hip-hop (McDonald, 2013, p. 6). Quoting McDonald in My Voice is My Weapon: Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics of Palestinian Resistance, the best way to define music and resistance in Palestine is as “the conscious use of any music in the service of the larger project of Palestinian self-determination” (McDonald, 2013, pp. 5-6). In fact, in Palestine, protest music can even be found at wedding parties, or conversely, Palestinians may sing wedding songs as a form of protest (McDonald, 2013, p. 4).

In this paper, I will focus my research on hip-hop music in Palestine. Hip-hop in Palestine can be traced back to at least 1998, when Tamer Nafar, a young Arab living in the Lyd area of occupied Palestine, made his debut as a hip-hop musician under the moniker “Untouchable” (Batterridge-Moes, 2021). A year after adopting the name Untouchable, he invited his friend Mahmood Jrere and his brother Suhell Nafar to join him. In 1999, the first hip-hop group in Palestine was formed, and the trio named themselves DAM (Blood).

Gradually, the group began their creative process by recording a few songs. They independently distributed their music via social media, primarily through MySpace, where they uploaded their songs. An Arabic song titled “Meen Erhabi” (Who’s the Terrorist?) later became their breakthrough single (Batterridge-Moes, 2021). Hip-hop in Palestine is not dominated solely by DAM. Other groups include MWR, also based in the occupied Palestinian territories; Ramallah Underground, Checkpoint 303, and Boikutt in the West Bank; and PR (Palestine Rapperz) in Gaza.

Poems, Music, and Palestinian Struggle

Music and poems had close relations with Arabs, especially in this paper, Palestinian society. These things live in people’s traditions and are expressed in colloquial Arabic and characterized by their spontaneity. Music and poems are interconnected. The poems are often sung by professional poets at weddings, public festivals, and other joyous social events. (Darweish & Robertson, 2021). Furani (2013) stated the primacy of poetry over other genres, including novels, newspaper articles, speeches, and plays stemmed from more than this connection to an ancient form of Arab expressive life (81).

This ‘sung poetry’ became more important after Palestine was ruled by the first Israeli military regime (1948-1966). Most of the content tells the story of the resistance under military rule, freedom, and responding to the nakba (Palestinian catastrophe in 1948). According to Furani, those poems in this era functioned as an underground railroad of words among Israeli law subjected various media to official censorship. Poetry is easy to transmit, recite, memorize, and disseminate with relative freedom (81). Darweish and Robertson cited Nassar (2017), pointed out, the writings of the Palestinians during the Israeli military rule period, especially poetry and the role of culture, locate ‘their resistance against the state policies and the Zionist logic that underpinned them, within the larger context of Palestinian, Arab and international struggles for decolonization’. We can trace these tendencies from several works made by Palestinian poets in that era.

Darweish and Robertson, for example, documented some works sung by two Palestinian poetry-singer, Badriyya Younis (1915-2001) and Awni Sbait (1929-2008). Badriyya, a female Muslim poetry-singer widely known for her love song ‘ḥayyid ʿan il-jhaishi yā ghbaishī’ (‘Keep Away from the Army’). This song talks about the pride of a woman in her boyfriend who is known as a courageous fighter that always refused to surrender. Meanwhile, Awni was the male poetry-singer from Arab Christian Maronite community. His works focused on social and political issues and connection to and love for the homeland. Iqrith, his village that occupied by Israel in 1948 was central topic of Awni’s poems. His song, “Revenge” (1976) for example, describes his struggle to survive with pride and respect, and his refusal to bow to oppression. This poetry-song started with the explicit lyrics: I was born in Free Iqrith!

Awni is also known as an internationalist and close to the communist idea. Some of his works related to the workers and peasants or international solidarity. Darweish and Robertson wrote: “He articulated the future relationship between Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Palestine, using song to urge Israeli leaders to ‘leave your expansion policy and racism, and let Ahmad, Haim and Hanna live in peace’ (Sbait, 1976a, 1976b, p. 23)”. According to Furani, after the 1967 war, literary critic and novelist Ghassan Kanafani started to promote these kinds of works as adab al-muqawama (resistance literature) (86).

Sung poetry was also not divided from the wedding party. As I mentioned above, according to McDonald, we can find protest songs at the wedding party, or vice versa, wedding songs at the protest. This phenomenon is related to the wedding party that consider a significant social occasion for the Arabs/Palestinian community. Wedding parties, especially those held in the main square (Bydar) would become an important event for the community. As the prominent event for the community, which many people invited, no wonder, the celebration would be held with great fanfare. Poet singers as entertainers performed to make the party more rousing.

In the Palestinian context, poet singers as Younis and Sbait utilised wedding parties to express connection to the land and opposition to military rule. Their songs promoted Pan-Arab national solidarity and Palestinian nationalism and identity, and, unlike many poet-singers, they rejected overt cooperation with the new regime ((Darweish & Robertson, 2021). Furani wrote:

Moreover, like weddings, in their familiar use of traditional forms, these events enabled people to come together, despite their individual fears and frailties, so that something new could begin in the world. In a collective struggle for survival, Palestinian poets sang to a public thirsty for their words, a public in need of a refuge that language was best left to provide. Poets helped their public confront fear and mobilize courage at a time when, as the poet Hanna Ibrahim puts it, “Simply raising your voice was an act of courage.” Palestinian poets countered repression with defiant “songs,”41 perhaps most famously exemplified by the 1964 poem-turned-song, by a young Mahmoud Darwish. (89)

Joseph Massad (2003) categorizes Palestinian songs against zionist colonization into several decades. Every decade had a different format, genre, and topic. During the 1950s, these songs spread through the mass availability of transistor radios, and in the 1960s through television sets. In these decades Palestinian songs tend to express the confidence of the Nasirist Revolution in Egypt. This revolution explodes in 1952 and celebrated not only by Egyptians but also Arabs. Its hopes of liberating Palestine and Algeria. It’s different from the music that emerged in the 1970s or at least after the 1967 war. In this decade, the songs spread by the cassette players and expressed the despair of defeat or hope in the Palestinian guerrilla movement then emerging (21).

The song about the Palestinian struggle against zionist colonization also cannot be limited by the territory. Since the Nakba in 1948, songs about Palestine spread over the Arab world. Popular singers such as Najah Salam from Lebanon, Farid al-Atrash in Syria, and Muhammad Abd al-Wahhab in Egypt have a song about Palestine. Abd al-Wahhab’s song, called “Filastin” (released in 1949, but written and composed in 1948 by Ali Mahmud Taha) even became the famous one.

McDonald stated many Palestinian musicians active during the first intifada (1987-1993). In this period, Palestinian music tended to fall into two categories: propagandist calls for martyrdom or transnational pop songs with little relevance to contemporary Palestinian experiences of violence and exile (5). In music, the first Palestinian intifada also marked the revival of the early 1970s popular heritage festivals in the West Bank featuring folk poets as representatives of national culture and practice (124). Besides that, it also emerged the underground music culture among Palestinian musicians. Some of them recorded their songs underground, in secret studios, and distributed their music hand by hand in the demonstrations that took place during the first few months of the intifada.

To avoid persecution from the colonial regime, they used pseudonyms to identify themselves. For example, In West Bank, there are Sabaye al-Intifada (Youth of the Intifada), Ibna al-Bilad (Son of the Nation), and al-ʿAmal al-Shaʿbi (The People’s Work). They’re the underground names of important artists and ensembles working in the resistance movement (125).

There is a different type of protest music that emerged in the West Bank and Hamas’s Gaza. In West Bank, many protest music oriented by the secular nationalist or even Marxist third-world guerillas against imperialism. It showed not only by independent musicians but also composers affiliated with parties like the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization) and PFLP (Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine). The music tends to be influenced by folk, traditional Palestinian music, or even Western music.

Meanwhile, in Gaza, that led by the Sunni conservative group HAMAS, the music that is more famous is anashid. In Gaza, anashid was derived in large part from the language of the Qur’an (references to Qur’anic scripture) and the sunna (the recorded deeds of the Prophet). According to McDonald, it formed the core vocabulary for imagining Palestinian liberation. The nation itself was envisioned as a pious community of believers, or umma. To this end, Anashid presents a reconceptualized vision of the nation framed within the discourses of religion and faith (128). This different influence also affected the musical expression in those two parties. For people in West Bank, dabke (traditional Palestinian dance) is common in musical attractions. But for HAMAS in Gaza, this dance is not suitable in terms of religious jurisprudence and modesty. Public dancing was not considered an appropriate activity in mixed (male/female) contexts. Also, for musical instruments. For HAMAS’s anashid, melodic instrumentations are forbidden. Many of these texts were sung in an unmetered free rhythm. However, it was not uncommon for vocalists to be accompanied by modest percussion, perhaps one or two daffāt (frame drums) (129).

Recently, the music of this era was found and popularized again. In 2022, London-Palestinian filmmaker and actor, Mo’min Swaitat, for example, uncovers banned revolutionary album ‘The Intifada’ by Riad Awwad, released in 1987(Music of the First Palestinian Intifada Re-Discovered & Restored, n.d.). This Riad’s record, he found in the old cassette store in the West Bank city of Jenin. He bought it together with 10.000 other tapes that he brought in five pieces of luggage to London. To Guardian, Swaaitat said, Riad Awwad’s record is one of the most special finds. It was only bright yellow tape with no information on it except a sticker with the hand-written word ‘intifada’ (McKernan, 2022).

Swaitat listened to the album several times, captivated by the poetic lyrics describing a lost homeland and the struggle for freedom. He never even knew the composer, until the composer called himself in the part of the tape, Riad Awwad. Swaaitat then knows more about Riad after he explores and traces Riad’s family in Palestine. He then met with Riad sister, Hanan, a famous writer and activist now in her 70s. According to Hanan, Riad is a Palestinian electrical engineer with a passion for music. During the first week of the Intifada, Awwad gathered his family to call upon their assistance in creating an album that would sing the song of the Palestinians at that time.

Hip-hop in Palestine never came until the mid of 1990s. This music emerged as a new Palestinian musical subgenre that mixes Arabic traditional music and melodies, American Hip Hop beats, with Arabic, English, or even Hebrew lyrics. The use of Hebrew lyrics can’t be separated from the condition that situated some Palestinian or their descendants living in Israeli-occupied territories, such as Lyd and Haifa. Some Palestinian Hip Hop groups are based in these areas like DAM from Lyd, or Walaa Sbait, an Iqrith-born music-composer, and activist that raise in Haifa. Palestinian Hip Hop also consider by the Palestinian diaspora or their descendants in the western world. It’s like Palestinian female rapper, Shadia Mansour who raise in London, United Kingdom. Maira (2008) called this a transnational perspective on Palestinian hip-hop. It’s situated in the context of a political movement and youth culture that spans national borders and that links the Western world with Palestine.

Hip Hop in Palestine was influenced by American hip-hop artists like Tupac Shakur and its spread by MTV. Mahmood Jrere one of DAM’s member said to SOAS, Tupac’s song “Holla if Ya Hear Me” which share the experience of living in the street became popular for the Arab teenagers in Lyd because it considers representing their live. To SOAS, Mahmood said:

“We lived in a project, in poverty, there was crime and police chasing us … It was the same thing I was seeing in the video. I didn’t understand every word, but I understood the pain and the struggle.“

No wonder in their earliest record, they explain that situation explicitly. Like in “hwn ‘anuldt” (Born Here) song, Mahmood takes this verse on his rhyme:

Let me introduce to ya’ll myself, I’m from a town called Lyd

You can find here all kind of unlocked criminals

The only thing people here did wrong was living on their land

As the poetry-song movement in Palestinian on the past, this hip-hop scene also related to the roots and identity as Palestinian and portrays their struggle and history. Its common for Palestinian Hip Hop musicians or DJ taking a music sample from traditional dabke songs, oud guitar sound, poems from Palestinians poets, or speech from the politicians/activists.

In their debut album, “Ihda” (Dedication) released in 2006, for example, DAM started the album with the speech of Gammal Abdel Nasser. If we refer Massad (2003) it’s like the 1950s Palestinian music that tend to express the confidence of the Nasirist Revolution. Orr (2011) stated: The opening lines from Nasser are charged with layers of meaning that display DAM’s unique nationalist rhetoric. As Palestinians living within Israel, the members of DAM are channeling Nasser’s words not only for the historical memory of their power to unite, but also for the memory of their power to confound and frighten the Israeli public (8).

Palestinian Hip Hop/Electronic music collective, Checkpoint 303 also put Ghassan Kanafani interview with Australian TV Journalist. Richard Carleton on their song entitled “Gaza Sea Minor”. This is intertwined with the serene oud sound and the recorded sound of the Gaza Sea which conveys the listener’s imagination of Palestine. The song includes an obituary of Ghassan, which was blown up by Mossad in his car in 1972. Checkpoint 303 is also repeating part “will continue fighting till death!”.

Besides the story of living under occupation and transferring the spirit of struggles, London-Palestinian rapper, Shadia Mansour to SAMAR media mentioned the important to promote Palestinian/Arabs identity through hip hop. Shadia who considers herself as “Palestinians of exile” said her songs inspired by her life experiences. Shadia said, when someone writes a song or works on a project involving the cause or the country, there’s always another path that comes afterwards that leads to the Arab of Palestinian identity.

And she believes Palestinians existence today, outside or inside Palestine, are resistance.

“We’re facing media that misrepresent our people. Not just Palestinian but also Arab people. That’s why we have to preserve everything, it’s a matter of existence,” Shadia said.

No wonder if Shadia lyrics tend to be re-emerging Palestinian heritage. In their song “El-Kofeyye Arabeyye” (Arabic Kufiyeh), she wrote:

I’m Shadia Mansour

And the keffiyeh is my identity

From the day I was born

The people have been my responsibility

Look, I was raised between the West and the East

Between two languages, between the rich and the poor

I’ve been life both sides

I’m like the keffiyeh

No matter how you wear me, wherever you leave me,

I stay true to my origins: Palestinian

She also shows that in her appearance. Shadia always performs in traditional Palestinian dress. For her, this dress is her statement to emphasize her identity as Palestinian.

Conclusion

Referring to the facts above, I assumed Hip Hop music in Palestine encapsulates much of the resistance music that has been the trigger and encouragement for the resistance of the Palestinian people. Those emerged since the era of poetry-song of the 1950s into patriotic songs throughout the first intifada in the late 1980s to the early 1990s. Hip hop which originated from the Black youth culture in America in the 1970s also inspired a lot of space for Palestinian Hip Hop artists to express their experience living under Israeli occupation.

Hip Hop lyrics in America, for example, that criticize racism and discrimination against black people are interpreted and compared by Palestinian youths with their condition against Israel (for Hip Hop activists who live in Palestine) or the discrimination they encounter as an Arab minority in the occupied Palestinian territories. Moreover, turning poetry into song lyrics is a Palestinian tradition from ancient times.

The wide range of Hip Hop music, because it relies on beats from DJs who can mix a lot of kinds of music, also allows Hip Hop to cover many types of music in one song or beat. No wonder, much of the Palestinian Hip Hop group’s material can include elements of traditional Palestinian music such as dabke and oud guitar. Also, as DAM and Checkpoint 303 do, Hip Hop also allows DJs to incorporate poetry or speeches into the structure of their music.

Hip Hop in Palestine is also seen to continue to develop and regenerate. Recently, for example, there was MC Abdul (Abdel-Rahman Al-Shantti), a Gaza kid born in 2008 who made a sensation in 2020 by rapping with his schoolmates at a school in Gaza. Even though he is still relatively young, Al-Shantti looks to inherit the ability to compose poems from his Palestinian ancestors with his expertise in singing rap verses as was done in the late 1990s by DAM. Like almost all Palestinian hip-hop artist, the songs that Al-Shantti later composed are also not far from his experiences living amid the onslaught of Israeli attacks. In an interview, he stated “The power that I have in my pen when I’m writing, I am unstoppable. The microphone is the only escape possible”(MC Abdul, 2021).

Palestine Street, a hip-hop group from Bethlehem, said that hip-hop helps young Palestinians, especially those living in refugee camps, face frustration and anxiety. Hip-hop teaches them to talk honestly about everyday life. To Aljazeera, Hefawi, one of the group members said, “Throwing stones at soldiers is a way of expressing yourself, a way of releasing your frustrations. When you throw a stone at a soldier, you are demanding a better life. And when we discovered hip-hop, we used that same energy that used to draw us to the streets to throw stones” (Palestinian Hip-Hop Group Uses Music as a Weapon | Occupied West Bank | Al Jazeera, n.d.).

Palestine Street since 2013 organized the hip-hop workshop for the kids in refugee camps across the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem. As they believe in Hip Hop, they teach rapping to Palestinian youths to channel their anger and frustrations into rap music, while still standing up for Palestinian rights. These efforts, once again, emphasize the relationship between music in Palestine and people’s resistance. And for a decade, Hip Hop played a key role.

Muhammad Irfan (irfanism90@gmail.com) is

a master’s student at Inter-Asia Cultural Studies National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taiwan. His research focuses on the youth movement related to the independent music and subculture. His works included a book “Bandung Pop Darlings: Catatan Dua Dekade Skena Indie Pop Bandung 1995-2015” (2019) about the indie pop music scene in Bandung, Indonesia and a video essay entitled “Numpang Gandeng: A Video Essay Explores The Indonesian Underground Music Scene in Taiwan” (2022). In 2024, he also hold two exhibition in Taiwan, “Have You Ever Met Dao Ming Tse” for Taipei Biennial 2023-2024 in January and “Rocking Indonesia: A Cultural Legacy of The Rolling Stones in Bandung” at TheCube Project Space, Taipei from August to October.