Hyun Jeong Ha (Duke Kunshan University)

The Lebanese film Where do we go now (2011) begins with a procession of dozens of women to a cemetery in a secluded village. The women in black slowly march as a group, each one beating their chest with their hands out of deep sorrow at losing their loved ones. Upon arrival at the cemetery they separate. The Muslim women on the right mourn as they kiss tombstones and the Christians on the left kiss the crosses laid on the graves. The sectarian clashes that killed mostly male villagers is now history, but their grief still remains.

The faces of the village women overlapped with Egyptian Christians grieving the deaths of Christian worshippers caught in a suicide bombing at the Botroseya church (St. Peter and St. Paul’s churches) in December 2016. The film featured clashes between the villagers, while in reality, Christians were attacked by armed militants. This pre-planned attack has become a more frequent type of sectarian violence in recent Egypt with ISIS’s gaining of international prominence in 2014. This bombing was particularly surprising to many Cairenes because attacks on church buildings were something they believed to only take place in other parts of the country – places like Upper Egypt or the city of Alexandria where more radicalized militants or Islamists are based. As one of my interview participants, who lost her old church friend from the aforementioned bombing, said, this event made Christians living in the center of the country more concerned about their safety.

Who are Egyptian Christians, and how would political changes in the post-Arab Uprisings, particularly under Sisi’s rule, affect Christian-Muslim relations? To answer these questions, this essay will start with a discussion of what constitutes Egyptian Christian identities, followed by a discussion of the political and social circumstances that the resurrection of the authoritarian regime has brought about since 2014. It has been almost ten years since the Arab Uprisings overthrew several long-term authoritarian regimes in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), including Tunisia’s Ben Ali, Egypt’s Mubarak, Libya’s Gaddafi, and Yemen’s Saleh. Myriad studies have examined how protestors were mobilized and what their demands were with an analysis of socioeconomic conditions under which people lived and sometimes had to endure. With politics in transition, studies on the post-Arab Uprisings predominantly focused on major political actors and changes in politics, which left religious minorities largely absent from the political arena. This essay focuses on unfolding sectarianism, or Christian-Muslim relations. It draws on ethnographic data collected in Cairo, supplemented by secondary literature, to understand where Egyptian Christians stand with the current political changes. Some of the quotes from in-depth interviews with Egyptians appeared in this essay are from the data I collected through multiple field research trips to Cairo between 2014 and 2018.

Coptic Orthodox Christians: “Original” Egyptians and Coptic pride

“Do you know what Coptic means? (ta‘rifī el-ma‘nā qibtī?)

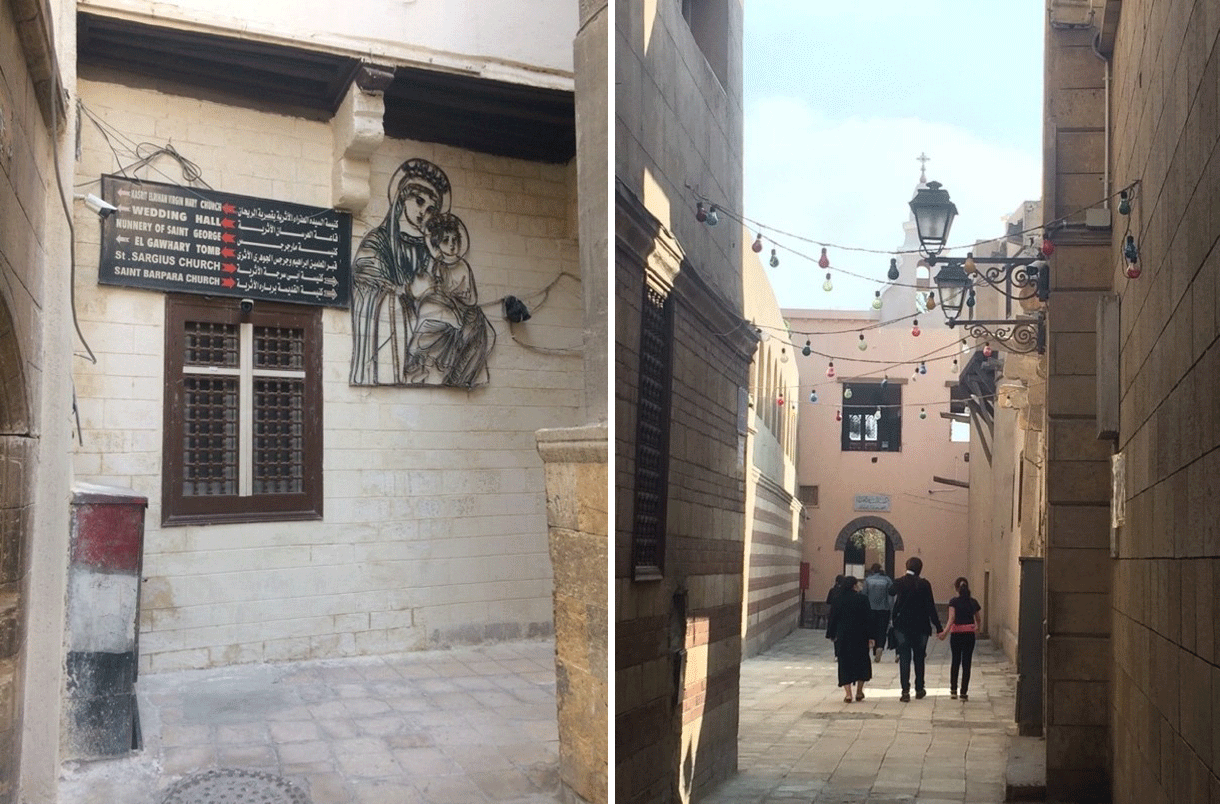

Most Coptic Orthodox Christians I met for the first time in Cairo in 2014 asked me this question. I first thought that they would just want to test how much I, as a foreign researcher, knew about them. Later I realized, however, that this was one of the ways that they start conversations with foreigners in order to emphasize their “originality” as Egyptians. Younger or older and regardless of gender, they were very interested in talking about their historical roots and that Christians resided in Egypt before Islam entered the country in the seventh century. The word “Coptic” derives from a Greek word Aigyptos, meaning Egyptian. In the past the word “Coptic” used to denote who or what is Egyptian; however, in contemporary Egypt its meaning has been narrowed down to indicate Christians only. Christians I met bragged about how they are “original” and are “lucky” to be Christians. They spoke of their perseverant ancestors who determinedly remained Christians, despite a number of legal restrictions. Old Cairo is one of the areas of Egypt with a high concentration of Christian residents and heritage sites, such as old church buildings and the Coptic Museum (see Figures 1 and 2).

© Hyun Jeong Ha

The history of Coptic Orthodox Christianity dates back to AD 42, when St. Mark established the first church in Alexandria. With the expansion of Islam, Egypt has become Arabized and Islamized, both ethnically and religiously. Christians lived under rule of the Islamic Empire for about 600 years and then the Ottoman Empire for a further seven centuries. Over these time periods, Christianity was recognized by the state but Christians lived under legal restrictions that consequently put them in position of second-class citizens. The Coptic language was banned in the tenth century, and since then it has no longer been used in daily conversations. Christians have spoken Arabic since then, and transliterated Coptic language in Arabic is used during Coptic Mass. Some churches offer Coptic language courses, but generally, only a limited number of Christians can speak the language.

The majority of the population in Egypt is Sunni Muslims with a small number of Shiis. Although the numbers are controversial, Egyptian Christians take up approximately ten percent of the entire population, equivalent to about nine million people. This makes Egyptian Christians the largest Christian minority in the MENA. Among the Christian population, Orthodox Christians are the majority, but Egypt is home to more than ten Christian denominations, including Catholics and Protestants. Besides Muslims and Christians, Egypt has a diverse composition of ethnic and religious communities, such as Bahais, Jews, and Nubians.

Unlike other ethnic and religious minorities in the MENA, Egyptian Christians have a strong territory-based nationalism (Baram 1990). Whilst some minorities struggle for national independence in the region, Egyptian Christians have a unified Egyptian identity. In this context, the Coptic Church has long refused to be referred to as minorities, despite their under-representation in the political arena and ongoing attacks on Christian communities. Pope Shenouda III (in Papacy from 1971-2012) in particular argued that Christians are as equal as Muslims, and the long history of Coptic Christianity cannot be reconciled with a minority status (Galal 2012).

Egypt after the Arab Uprisings: The rise of Islamist politics

The consecutive 18 days of protests, or the Egyptian Arab Uprisings, terminated the 30-year authoritarian rule of Hosni Mubarak. On the night of February 11, 2011, Taḥrir square, one of the major protest sites in Cairo, was full of Egyptians celebrating the Mubarak’s resignation. Those who chanted “bread, freedom, social justice (‘aīsh, ḥurīya, ‘adāla igtimā‘iya) throughout the protests finally cheered for victory and dreamed of a better future to come.

It was, however, not long after that Egyptians started to witness the rise of Islamist politics with the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) and Salafi politicians.[i] To gain as many seats as possible in the 2011-2012 Parliamentary election, the religious leaders and politicians worked hard to spread their political ideas across the country through online and offline platforms. Many of these messages were hateful, particularly to Christians: Salafis argued that Egypt should purify the national identity, making it wholly Islamic, and referred Christians to “kafir” (meaning pagan). They also campaigned to both revive jizya, an additional tax imposed on non-Muslims (Jews and Christians) under the Islamic Empires, and to remove Christians from mandatory military service on the grounds that they are not full members of society (Lacroix 2012).

It was not just Christians who felt fearful and threatened (Ha 2017); Muslims also expressed concerns about the radicalization of Islamist politics. When a series of Salafi protests were ongoing in Alexandria, a professional Muslim woman interviewed by Reuters said: “Alexandria isn’t the same any more … It’s losing its character and it will be unfeasible for it to return as the center for political and cultural freedoms” (Elyan and Youssef 2011). Although Alexandria has been a hub for arts and liberals, the city has long been a base for Salafi movements, particularly since 1926 with the start of Salafi Dawa‘.

The 2011-2012 Parliamentary election led to a success for MB’s Freedom and Justice Party and the Salafi coalition. Together, they secured 65.3% of the popular vote in total, gaining 358 of 508 seats (Sellam 2013).[ii] The increased support for these parties culminated in the election of the former MB member Muhammad Morsi as Egypt’s president in June 2012 (in office: June 2012- July 2013). His presidency, however, ended after a year by a military coup and mass protests from a population who were deeply unsatisfied with Morsi.

Egypt under Sisi and Christians in a predicament

The end of the Morsi government did not mean a peaceful, non-sectarian future for Egyptians. After Morsi was ousted, in August 2013, MB members and Morsi supporters gathered to proclaim the reinstatement of Morsi in Raba‘ and al-Nahda squares in Cairo. The then General, Abdel Fatah el-Sisi, violently dispersed protesters, which killed at least 817 protestors and 87 Morsi supporters in each square. Egyptian and international human rights organization strongly condemned the act as a “crime against humanity” (Human Rights Watch 2013).

In the following year, Sisi was inaugurated as president. Nothing would explain better than his visit to St. Mark’s Cathedral on the Christmas Eve on January 6, 2015 his efforts to recover relationships with the Church and Christian communities (see Figure 3). This was the first visit ever made by an Egyptian president in the country’s entire history (Volokh 2015). It was such a great relief for many Christians, whose life under Islamist and Salafi politics had put them on pins and needles throughout the past few years. Starting from 2016, he has also started to share congratulatory messages on Coptic Easter with Coptic Christian communities in and outside of Egypt (Egypt Today 2020).

The Egyptian government’s endeavor to address religious unity does not seem to help Christians improve relations with the Muslim majority. Unlike the friendly gestures to the Church, Sisi has implemented draconian measures that have widely limited political freedom since 2014. Upon his presidency, he initiated several processes, including legal reforms, to repress dissidents and to limit freedom of speech. The Sisi government adopted a new law in 2019, for example, that significantly restricts non-governmental organizations (NGO)’ movements. It confines the types of work that NGOs can do to developmental and social work in defense of national security (Aboulenein 2017). Upon the inscription of the law, civil rights organizations have widely criticized it for being the most restrictive regulation on civil society. Cabinet ministers first rejected for it being too restrictive. Over 46,000 organizations were affected by the law, and some activists were charged with taking foreign funds to create disorder in the country (Aboulenein 2017).

Furthermore, the government kidnapped and arrested anti-Sisi activists and researchers, not to mention reinforced monitoring and surveillance of anti-government social activists, especially liberals and leftists. State regulations on sexualities have also become intensive, with several crackdowns and sudden raids in places where LGBTQs frequent. Sarah Hegazi, a prominent queer feminist, died in exile after being tortured and sexually assaulted while imprisoned for three months on charges of raising the Pride flag at a concert in 2017 (Hird 2020). Additionally, a self-proclaimed atheist blogger was detained for promoting his anti-Islam views on social media and sentenced to three years in prison for insulting the judiciary during his trial (The New Arab 2018).

In these pressing political and social circumstances, the government’s friendly gestures towards the Church rather seem to harm Christians. Some Muslims blame Christians for political repression because they believe Christians widely voted for Sisi in the 2014 presidential election. A Muslim woman in her late 60s who I was talking with in April 2018 blamed Christians for Sisi’s election. Although she understood that Christians want the state to protect them because they are fearful of violent Islamists, she attributed the return of the authoritarian leader to Christians. The Church has been standing behind the authoritarian regime from the 1980s, after the then Coptic Pope Shenouda III returned from house arrest for openly criticizing Anwar Sadat (in presidency from 1970-1981)’s rule in 1981. Hosni Mubarak (in office from 1981-2011) reinstated him in 1985, and from then on the Pope was compliant with the regime until he passed away in 2012 (Hasan 2003).

Sisi thus far has embedded an authoritarian regime and laid the groundwork for long-term rule. His reelection in 2018 carries some doubts in terms of transparency as other candidates were arrested, imprisoned, or disappeared, before the election. He revised the Constitution in 2019 to extend the period of reelected presidency from four to six years, which would lead Sisi to be in office until 2030 if he gets reelected in 2024. In July 2020, he banned retired army officers from seeking for candidacy for election, and this is likely to remove the potential for future competition (Reuters 2020).

Where do Christians go now?

The village in the Lebanese film has no name, and villagers live in an uneasy peace. One of the messages to take away from this essay related to this point would be that sectarian relations in Egypt hold lessons applicable to other cases, as this is also conveyed in the aforementioned film. Women try their best to curb any violent incidents. They collect and bury guns and draw men’s attention to something else when they think sectarian tensions are heightened. But it did not seem to be enough to prevent the violence. The sectarian clash at the end of the film suggests that sectarianism does not easily fade once it has become rooted. Emotions run deep between Egyptian Christians and Muslims, with the strong presence of the current regime shaping how and when they might emerge.

This essay discussed how the state’s friendly gestures towards the Christian community seem promote religious unity at the surface level. Underlying consequences, however, may exist. Some Muslims have become unhappy with the state-Church coalitions as the government has reinforced control over civil society, thus repressing the spirit of the Arab Uprisings. Behind the coalition between Muslims and Christians lies a layer of sectarian tension that Sisi’s authoritarian regime risks bringing to the surface.

About the author

Hyun Jeong Ha (hyunjeong.ha@dukekunshan.edu.cn)

is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Duke Kunshan University located on the outskirts of Shanghai in China. Ha received her Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Texas at Austin in 2017 and was a Global Religion Research Initiative postdoctoral fellow in the Center for the Study of Religion and Society at the University of Notre Dame. Her research interests lie at the intersection of religion, power, and gender in the Middle East. At Duke Kunshan, she teaches courses on social theories, social problems, and the ethnography of the Middle East.

[*] I wrote this essay with support of 2020 Visiting Scholar Fellowship at Seoul National University Asia Center.

[ii] See Toft (2013) on religious outbidding in political transition. She argues that religious outbidding takes place when political elites in transition reframe secular movements as religious in order to disband and weaken political opposition.

[iii] Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party gained 37.5% support and the Salafi coalition gained 27.8% (Sellam 2013).

[iv] The image is available at https://www.flickr.com/photos/coptic-treasures/27863450507/in/photolist-2jbZPvH-Jsct66

References

- Aboulenein, Ahmed. 2017. “Egypt issues NGO law, cracking down on dissent.” May 30. Reuters.

(https://www.reuters.com/article/us-egypt-rights/egypt-issues-ngo-law-cracking-down-on-dissent-idUSKBN18P1OL) - Baram, Amatzia. 1990. “Territorial Nationalism in the Middle East.” Middle Eastern Studies 26(4): 425–48.

- Egypt Today. 2020. “Sisi Congratulates Egyptian Christians Abroad on Easter Sunday.” April 16. Egypt Today. (https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/1/84793/Sisi-congratulates-Egyptian-Christians-abroad-on-Easter-Sunday).

- Elyan, Tamim, and Abdel Rahman Youssef. 2011. “Stric Muslims Stake Claim on Egypt’s Political Scene.” Reuters, 2011. (https://www.reuters.com/article/us-egypt-election-salafis/strict-muslims-stake-claim-on-egypts-political-scene-idUSTRE7AK0OF20111121).

- Galal, Lise P. 2012. “Coptic Christian Practices: Formations of Sameness and Difference.” Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 23(1): 45–58.

- Ha, Hyun Jeong. 2017. “Emotions of the Weak: Violence and Ethnic Boundaries among Coptic Christians in Egypt.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40(1):133–51.

- Hasan, S S. 2003. Christians versus Muslims in Modern Egypt: The Century-Long Struggle for Coptic Equality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hird, Alison. 2020. “Egyptian LGBTQ activist, who dared to raise the Pride flag, takes her own life aged 30.” Radio France Internationale. June 18. (https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20200618-egypt-lgbtq-activist-sarah-hegazi-suicide-gay-rights-repression-al-sissi)

- Human Rights Watch. 2013. “Egypt: Rab’a Killings Likely Crimes against Humanity.” August 12. https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/08/12/egypt-raba-killings-likely-crimes-against-humanity

- Lacroix, Stéphane. 2012. “Sheikhs and Politicians: Inside the New Egyptian Salafism.” Doha Brookings Center. June.

- Reuters 2020. “Egypt’s Sisi approves ban on retired army officers standing for election.” July 30. Egypt Independent. (https://egyptindependent.com/egypts-sisi-approves-ban-on-retired-army-officers-standing-for-election/)

- Sellam, Hesham. 2013. Egypt’s Parliamentary Elections 2011-2012: A critical guide to a changing political arena. Washington DC: Tadween Publishing.

- The New Arab. 2018. “Atheist blogger arrested in Egypt for anti-Islam criticism.” May 5. The New Arab. (https://english.alaraby.co.uk/english/news/2018/5/5/atheist-blogger-arrested-in-egypt-for-anti-islam-criticism)

- Toft, Monica D. 2013. “The Politics of Religious Outbidding.” Review of Faith and International Affairs 11(3):10–19.

- Volokh, Eugene. 2015. “El-Sisi Becomes First Egyptian President to Visit Coptic Christmas Mass.” The Washington Post, January 8, 2015. (https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2015/01/07/el-sisi-becomes-first-egyptian-president-to-attend-coptic-christmas-mass/.)