지연정 (한국외국어대학교)

At present, India appears to be the most interesting de facto nuclear weapons state. India’s nuclear history evinces a highly convoluted trail that no other country has been able to emulate: the nation’s 1998 nuclear tests occurred after a long-time gap from the institution of the Atomic Energy Commission in 1946 and a peaceful nuclear explosion in 1974. The unconventional pattern of the schedule of India’s nuclear development in comparison to other nuclear weapons states has caused India’s nuclear program to often be encapsulated in numerous and varied connotations: deliberate ambiguity, strategic restraint, or the absence of a strategy. Among those denotations, India’s nuclear posture was generally defined as a reactionary posture due to the salience of strategic restraint; however, the current debates on India’s nuclear doctrine is more open to deduction as some of evolving signs have produced a diverse understanding of India’s future strategic and doctrinal choices.

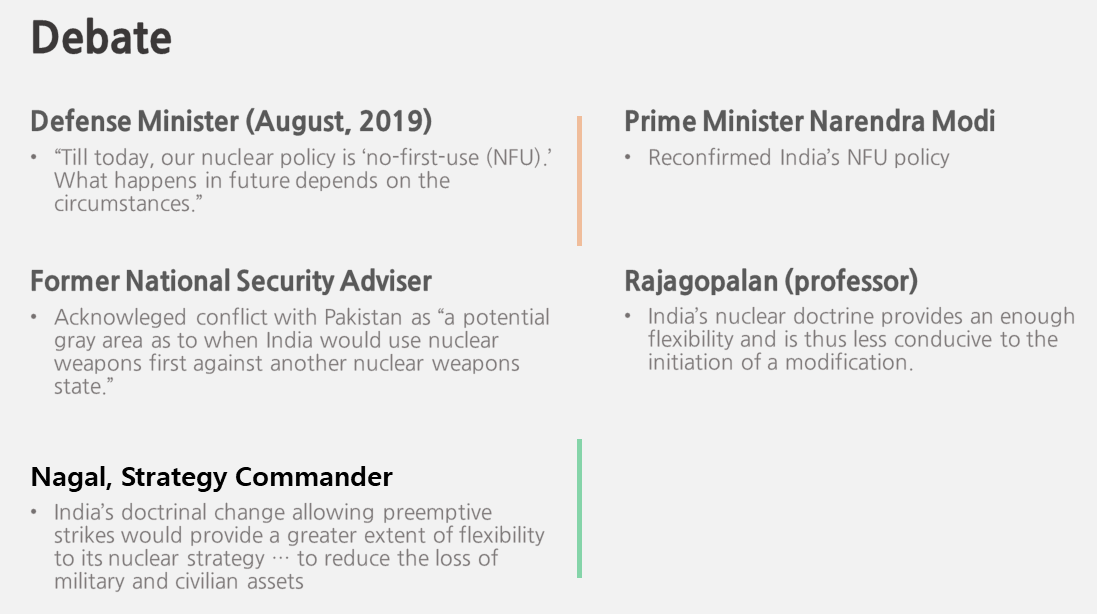

In an event to mark the 21st anniversary of India’s nuclear tests on August 16, 2019, India’s Defense Minister Rajnath Singh triggered a world-wide speculation on India’s nuclear policy when he stated “Till today, our nuclear policy is ‘no-first-use (NFU). What happens in future depends on the circumstances.”[1] This uncommon statement on the nuclear doctrine from India’s incumbent minister invited rigorous debates in many spheres, extending from regional nuclear rivals to India’s global reach. In fact, this statement was fairly streamlined with previous signals provided by other retired government officials and some believe that it apparently delivers a non-partisan call for policy change. Thus, fundamental questions arise: What strategic and doctrinal choices can India contemplate in order to review, modify, or alter its nuclear policies? How would the nuclear force posture that ensues from such a policy change be followed in the future? The current scholarly debates vary between two extrapolations of whether or not India could change its current policy position and recalibrate its strategic benefits. Thus, a developing deliberation is indispensable to the forecasting of India’s future strategic choices and to the tendering of a full account of the issue.

India’s Nuclear Doctrine

The Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) election manifesto for the Indian general elections of 2014 have elicited heated discussions over the last five years on the country’s prospective nuclear doctrine. Debates continue on India’s possible doctrinal changes, strategic calculations, military preparedness, future costs, and the rebounding ramifications from its nuclear rivals. Unlike some provisional demands for a review of the doctrine in the early 2010s (including a trial investigation conducted by the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies in 2012) the arguments following the 2014 elections have been instigated by scattered revelations offered by formal or incumbent government officials and military heads. These disclosures concern the possibility of a serious governmental review and modification of India’s nuclear doctrine in the future. The time-threshold that would ultimately make the government publicly announce the launch of such a review process or its potential outcome is uncertain. However, it is probable that a review discussion is already contemplated, or that a revision might have been considered.

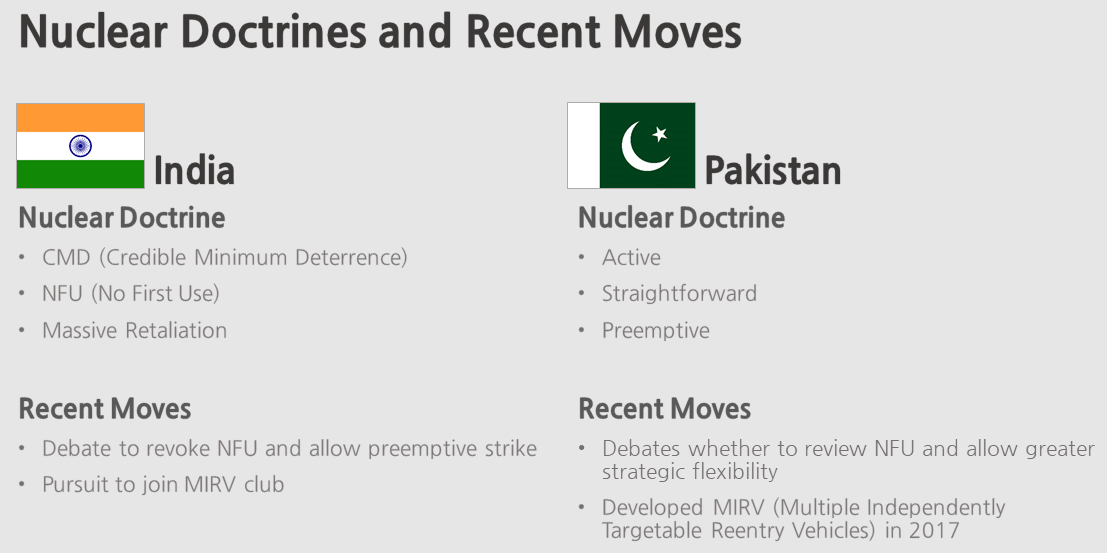

Notably, a series of hints have been dropped over the last five years. In its election manifesto, the BJP promised to “study in detail India’s nuclear doctrine, and revise and update it, to make it relevant to challenges of current times” and to “maintain a credible minimum deterrent” while not promising NFU.[2] NFU comprises the core tenet of India’s nuclear doctrine and this policy sustains the significance of India’s nuclear posture. The nuclear doctrine approved by India’s Cabinet Committee on Security in January 2003 contains three significant features: the self-identification of India’s nuclear posture as “credible minimum deterrence (CMD),” a central strategic consideration based on “NFU,” and the military assurance of a “massive retaliation”.[3] In the absence of a white paper, India’s voluntary imposition of strict guidelines for itself with regard to its nuclear posture is uniquely valuable to the understanding of the core precepts of its nuclear policy direction.[4] Thus, any changes in the doctrine or even a modicum of review would invite a rippling effect to the interpretations of the multi-layered changes occurring in India’s larger strategic calculations and its military strategy.

The evolving debates on the doctrine appeared to maintain bipartisan indications of possible changes, yet, the accounts are often conflicted and are imbued with various degrees of ambiguity. The former National Security Adviser Shivshankar Menon’s point of view posited in his book Choices was one of the most-cited references after the BJP’s 2014 election manifesto was revealed. He said, “India’s nuclear doctrine has far greater flexibility than it gets credit for.” Some of his views elucidate even more specific counterforce strategic circumstances against its regional nuclear rival, Pakistan. For instance, his acknowledgement of “a potential gray area as to when India would use nuclear weapons first against another nuclear weapons state” appeared to insinuate that India could be contemplating wider options than the conventional wisdom of the NFU policy. [5] His revelation of India’s more active counterforce tactics prior or in response to Pakistan’s (probable) use of tactical nuclear weapons (TNW) implies a window of opportunity for the launch of “a massive Indian first strike” or a “comprehensive first strike” against Pakistan. Given that Menon’s position was pivotal to India’s nuclear strategy between 2011 and 2014, the three points of thought posited above are sufficient in instilling doubts about the conventional wisdom of India’s nuclear posture of CMD, counterforce retaliatory strategy, and NFU. Such assertions augment speculations about India’s first strike scenario on its Western front.[6]

The heated discussions on the revocation of NFU are further heightened by other central figures in India’s nuclear strategy loop. A former Strategic Force Commander, Lt. Gen. BS Nagal, has argued that the NFU stand lowers India’s credibility for nuclear deterrence. A similar idea has been made public by the former Defense Minister Manohar Parrikar, remarks also opened new ground for discussions and caused the explosion of arguments regarding the sub-field elements of war scenarios. The most recent statement may be attributed to the current Defense Minister Rajnath Singh, as mentioned above. According to some researchers, this comment extends a pellucid sign of the erosion of India’s NFU principle.[7]

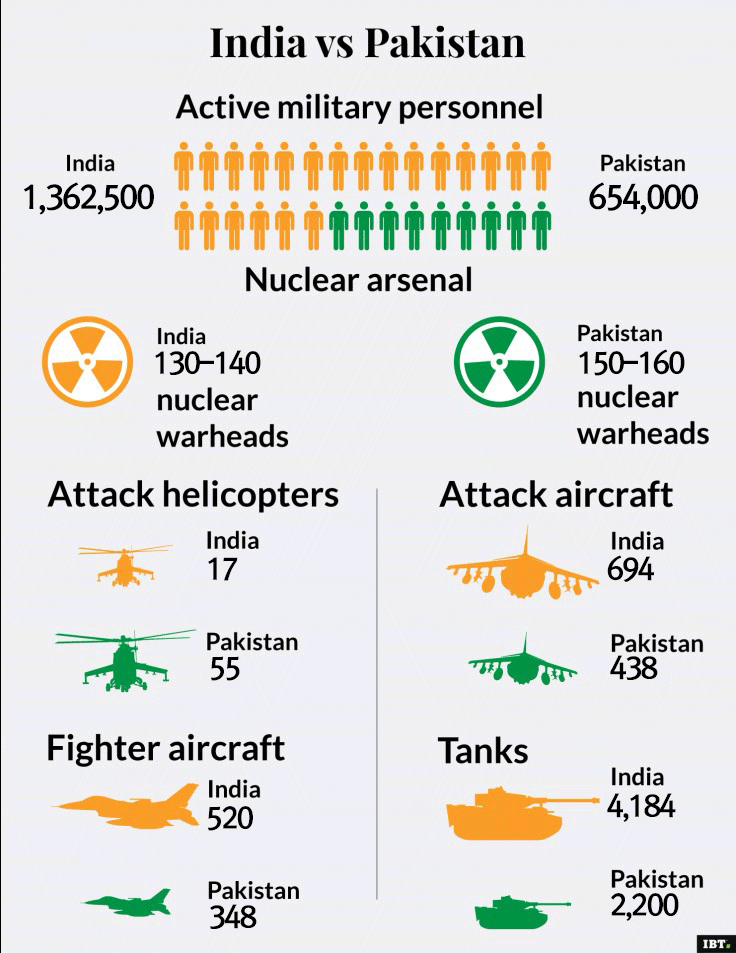

However, India’s reconsideration of the NFU policy is not new. It probably began when Pakistan’s TNW and its strategic plan were visualized in 2011. Oppressed by the asymmetric conventional force posture vis-à-vis India, Pakistan’s nuclear strategy involves more active, straightforward, and preemptive-conducive rationale to counterweigh India’s superior military presence. Pakistan’s flight-test of a short-range, nuclear capable ballistic missile named Nasr in April 2011 is believed to echo Islamabad’s all options open choice covering the full spectrum of deterrence against India. The battlefield scenarios have become more complex with the development of the TNW, inviting questions about Pakistan’s strategies of winning a potential war with India. Pakistan’s growing nuclear stockpiles and fast-moving strategic applications of nuclear weapons indicates that Islamabad would not take a passive approach in the event of a crisis approximating nuclear levels of warfare. Pakistan’s India-specific military strategy seeks maximum flexibility in the notion of broad deterrence, and it added a strategic layer with Nasr.

In addition, Pakistan’s claim of having achieved the multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRV) technology in 2017 extends the intricate security calculations for India. On January 24, 2017, Pakistan announced its first testing of a nuclear-capable MIRV named Ababeel, which is estimated to encompass a maximum range of 2,200 km. This medium-range ballistic missile is designed to increase Pakistan’s sustainability against India’s ballistic missile defense (BMD) system. Some doubts still remain about Pakistan’s success in developing a miniaturized nuclear warhead suited to MIRV-based military operations. However, Pakistan’s growing land-based missile capability led by MIRV certainly prods India to reinspect its development of a two-layered BMD system along with its MIRV program. Unlike the rivalry of the superpowers during the Cold War, the nuclear weapons states of South Asia require more effective military strategies vis-à-vis an immediate neighbor with smaller number of nuclear warheads and delivery vehicles. Therefore, the vigorous demands to discuss India’s nuclear doctrine are not incongruous in response to changing South Asian security dynamics.

With regard to the South Asian crisis escalation scenario, some conventional deterrence optimists believe, however, that bilateral nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan is unlikely.[8] It is likely that the nuclear adversaries in South Asia would foster escalation control measures that would bind them to a lower-level conflict. Optimists regard the Kargil conflict of 1999 or India’s surgical strike of 2016 as examples of escalation control exercised in practice; nevertheless, it brushes aside far more circumstantial, accidental, and inadvertent scenarios as nuclear pessimists observe. Hence, many experts apprehend the escalation matrix differently, thereby offering differing views on India’s NFU and non-NFU scenarios.

The Debates

The ongoing debates on India’s nuclear doctrine incorporate two categories. First, those who question the NFU policy believe that India’s internal review may have been contemplated as an attempt to switch from the side of equating the CMD and the NFU to the other aspect of gravitating toward CMD rather than the NFU diktat. A few extreme voices further speculate that India may weigh credible deterrence over CMD, referring to the Indian Armed Forces’ Joint Doctrine in 2017.[9] However, the focal point of the debates vests in the possibility of India revoking the NFU policy; and this conjecture is thus far strictly confined to India’s Western front nuclear war scenario.

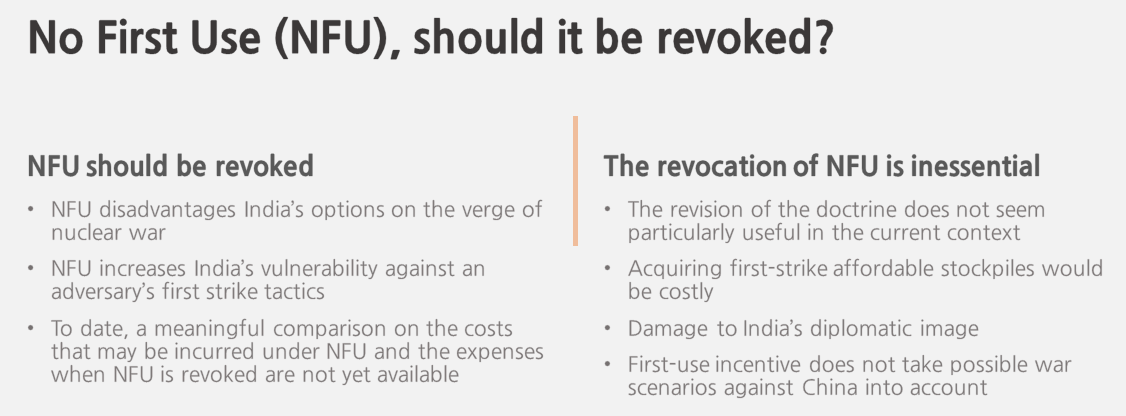

Those who advocate the revoking of the NFU policy posit an obvious reason: the NFU rule disadvantages India’s options in the event of crisis escalation and on the verge of nuclear war. India’s NFU bears a clear-cut defensive nuclear posture, and pledges India to a nuclear response only when an attack is equivalent to the use of weapons of mass destruction attack. This retaliatory stance increases India’s vulnerability against an adversary’s first strike tactics and could favor an inestimable scale of attack against India. India’s nuclear doctrine is designed to respond and its reactive restrictions narrow India’s maneuvering options if the country faces an impending nuclear threat. The NFU policy also imposes the heavy burden of survival on the first-strike recipient for it to exercise effective second-strike nuclear capability. If India’s nuclear adversary engages in all-out war without following a gradual escalation pattern, the guaranteed retaliatory mechanisms, and successful nuclear operation would be limited in leadership, command, and control paralysis under the existing NFU. The operational-level responses would have to challenge an enormously cumbersome circumstance in crisis according to some in the military community who express concerns in India’s NFU. Further, it would be inconceivable to expect an automatic de-escalation process to play out in favor of India’s NFU during a war, as Nagal argues, “no adversary will initiate a nuclear war only to de-escalate a conventional war in a very limited battle area.”[10]

This logic appears to be streamlined with policy circles in India. Menon articulates, “If Pakistan were to use tactical nuclear weapons against India, even against Indian forces in Pakistan, it would effectively be opening the door to a massive Indian first strike, having crossed India’s declared red lines. … There would be little incentive, …, for India to limit its response, since that would only invite further escalation by Pakistan.”[11] India would gain the strategic incentive with a first strike option to protect the credibility of India’s nuclear force against Pakistan’s nuclear attack. As Nagal argued in his 2015 article, one of the primary goals of an (impending) nuclear exchange is “to terminate the war at the earliest.” India’s doctrinal change allowing preemptive strikes would provide a greater extent of flexibility to its nuclear strategy in its search for a feasible option to negate an enemy’s nuclear retaliation and to reduce the loss of military and civilian assets.

On the other hand, India’s nuclear doctrine somewhat already endows a strategic flexibility through a deliberate ambiguity. The doctrine does not restrain India’s second-strike principle only to a post-attack scenario; rather, it offers a prerogative interpretation for India’s political leadership to initiate a preemptive attack against a detected threat, launch on warning, or launch on launch pledging mutually assured destruction. Instead, India’s moral values may play a larger role in helping India to maintain its strategic restraint even in the event of a crisis while the ambiguity embedded in the doctrine provides a somewhat flexible response against the adversary. In the opinion of NFU skeptics, the political leadership’s reactive policy line or hesitance potentially qualifies India’s proactive strategic implementation. This reluctance may be more troublesome in dealing with an unpredictable and unstable adversary. The argument of NFU skeptics may anticipate the changes in doctrine and in particular, the revocation of the NFU, probably incorporates the necessity to eliminate domestic hurdles at a time of crisis. In terms of the nuclear weapons program, the revocation of the NFU policy is expected to galvanize the political and military leadership to be more active and alert in checking its profile of nuclear competition.

Second, others argue that the revocation of NFU is inessential. Rajagopalan and Sethi’s interview with the Hindu on August 23, 2019 calls for a prudent approach to the prevailing argument about the nuclear doctrine.[12] In Rajagopalan’s view, the arguments favoring the likelihood of changes ignore the government’s reiteration of conformity with the NFU policy “would possibly be an exaggerated reading of the statement [of officials].”[13] Moreover, In his view, India’s nuclear doctrine provides an enough flexibility and is thus less conducive to the initiation of a modification. While India’s partial or entire revision of the doctrine is a possibility under conditions of demand, it does not seem particularly useful in the current context. Sethi’s understanding is in the same vein but uses a different analysis. In her criticism on the exaggeration of interpretation by the “Nuclearazzi,” many seems to miss Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s reconfirmation of India’s NFU policy while extending congratulatory remarks on India’s first nuclear submarine INS Arihant’s first patrol in November 5, 2018.[14] In this view, the restructuring of the nuclear capability-building process adjusted to the first strike policy would call for a considerable financial and technological resources. Increasing current levels of inventory to first-strike affordable stockpiles, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities would be an onerous proposition for present India. Further, the damages incurred to India’s diplomatic efforts to join the nuclear nonproliferation regime including membership of the Nuclear Suppliers Group and the acquisition of a seat as a permanent member at UN Security Council would also be inevitably affected at the expense of altering the doctrine.

This view of political costs is also shared by others, and it is even partially acknowledged by first-strike advocates who desire India to revoke its NFU policy.[15] As a de facto nuclear weapon state, India’s self-regulatory nuclear doctrine has facilitated the establishment of an image of a responsible nuclear power. India’s post-2001 diplomacy has blossomed through its defined responsibility and has accommodated a cogent logic through which to distinguish between India and other nuclear pariahs. NFU has aided India in being viewed as a responsible nuclear power. This image plays out well in diplomatic realms; it also prevents political leaderships and military planners from taking offensive action. Therefore, concerns about the damage to India’s diplomatic image by revoking the NFU are valid; however, it is uncertain if India’s move toward first-use option would determinatively impair its diplomatic missions in practice. In Sethi’s candid assessment, the skeptical analysis of India’s nuclear diplomacy is secondary to the outlay of financial investments by India.

자료: 연합뉴스

Moreover, the first-use incentives in India’s nuclear scenario rule out a war with China. As neither India nor China’s nuclear doctrines include a first use plan, the threat from China is comparatively mitigated and vice versa. A few likely scenarios are possible where either Beijing or New Delhi would mull over a strategic nuclear first use against each other. Yet, the historical bilateral disputes between these countries do not invite any nuclear escalations. China’s well-dispersed strategic nuclear assets are not primarily aimed at India; neither gives China a clear sign to challenge India’s nuclear assets nor does it want to invite the country to enter into a dyadic arms race. In turn, India’s strategic goals encompassing CMD and NFU are enough to deter China’s limited nuclear use against India. In addition, New Delhi’s position of countering criticism on its growing nuclear capabilities such as BMD remains intact under its NFU policy. As the BMD prioritizes the protection of India’s strategic assets under a defensive nuclear posture, their reverse use is not contemplated in this proposition.

However, this argument also has some flaws. The broader consideration for India to comply with the NFU clause is cogent; however, discussions on the costs of increasing offensive capabilities under the first use policy vis-à-vis augmenting its defense abilities under the NFU are more or less conjectural. For instance, NFU advocates simply surmise that a pure retaliatory capability is less expensive than an expansive nuclear weapons program, which requires a more advanced intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) investment. However, pure retaliatory capability includes survival costs as part of the credible punitive nuclear capability. In a retaliatory scenario against Pakistan, India has to keep some of surviving counterforce capability including operational command and control. Its retaliatory nuclear launch capability has to be enough to deter Pakistan’s next move which would include conventional warfare. Some residual nuclear forces would also need to be maintained to exert credible deterrence against the nuclear rival on the Eastern frontier.

Furthermore, as massive retaliatory capability is written into India’s nuclear doctrine, and as the notion of credible nuclear deterrence requires a competent military capability, it is premature to conclude that retaliatory capability is less expensive than offensive capability-building in South Asia. For instance, India’s pursuit to join the MIRV club is inevitable under CMD, regardless of its adherence to the NFU policy, due to its rivals’ advancement. As long as India’s nuclear doctrine presents a CMD, India has to technologically master what other nuclear weapons states own, which includes Pakistan’s MIRV. The investment for competitive real-time ISR infrastructure also follows the same pattern. To date, a meaningful comparative study on the costs that may be incurred under NFU and the expenses that would be necessary in the instance of a shift in the policy are not yet available. While the NFU provides certain advantages to India’s nuclear posture, it is dangerous to determine that the price of conformity to retaliatory nuclear capability is inarguably less.

Conclusion

The current debates about India’s nuclear doctrine involves more complex war scenarios than ever before. India’s concerns about Pakistan offer the primary reason for demands to review its nuclear doctrine and to opt for a more flexible route of military action. Remarks made by some retired and incumbent government officials have added to the speculation that India may seriously consider revoking its NFU policy. Two contradictory signals are projected by experts on the possibility of such a measure. From the purely military point of view regarding India’s Western nuclear rival, the revocation of the NFU delivers a strategic flexibility to India in a possible war scenario. On the other hand, a doctrinal change would subsequently cost India’s nuclear program and the war scenario including the other nuclear rival in the East. While undetermined, the present debates certainly mirror India’s unending strategic calculations.

Ji Yeon-jung (yjji@hufs.ac.kr)

is a visiting fellow at Institute of Indian Studies, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Seoul.

She received a Ph.D. from Jawaharlal Nehru University and was affiliated with Harvard’s Belfer Center, and Centre for Air Power Studies in New Delhi.

Her research is primarily on nuclear strategy, nuclear arms race in South Asia, and grand strategy.

[1] Elizabeth Roche, “Rajnath Singh Sparks Debate on No-First-Use Nuclear Doctrine,” https://www.livemint.com, August 16, 2019, https://www.livemint.com/news/india/rajnath-singh-sparks-debate-on-no-first-use-nuclear-doctrine-1565978545173.html.

[2] “Full Text: BJP Manifesto for 2014 Lok Sabha Elections,” News18, accessed October 31, 2019, https://www.news18.com/news/politics/full-text-bjp-manifesto-for-2014-lok-sabha-elections-679304.html.

[3] India’s nuclear doctrine has eight main points; first, attaining a credible minimum deterrent; posturing No-First Use and the retaliation only to nuclear attack to Indian territory and forces; promising massive retaliation to inflict unacceptable damage; controlling retaliatory attack under civilian political leadership through Nuclear Command Authority; eliminating nuclear attack against non-nuclear weapon states; retaining an option to incur nuclear attack against WMDs; pertaining a strict control of nuclear and delivery vehicle related materials and technologies and self-moratorium of nuclear testing; continuing effort for nuclear free world. “The Cabinet Committee on Security Reviews Perationalization of India’s Nuclear Doctrine,” accessed October 31, 2019, https://www.mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/20131/The+Cabinet+Committee+on+Security+Reviews+perationalization+of+Indias+Nuclear+Doctrine.

[4] “The Cabinet Committee on Security Reviews Perationalization of India’s Nuclear Doctrine.”

[5] Christopher Clary and Vipin Narang, “India’s Counterforce Temptations: Strategic Dilemmas, Doctrine, and Capabilities,” International Security 43, no. 3 (Winter2018 2019): 17.

[6] Shivshankar Menon, Choices: Inside the Making of India’s Foreign Policy (Washington D.C., U.S.A: Brookings Institution Press, 2016).

[7] Christopher Clary and Vipin Narang, “India’s Counterforce Temptations: Strategic Dilemmas, Doctrine, and Capabilities,” International Security 43, no. 3 (WInter /2019 2018): 7–52.

[8] Michael Krepon, Rodney W. Jones, and Ziad Haider, “The Stability-Instability Paradox, Misperception, and Escalation Control in South Asia,” in Escalation Control and the Nuclear Option in South Asia (Washington D.C.: THe HEnry L. Stimson Center, 2003), 1–24.

[9] Vipin Narang, “India’s Nuclear Strategy Twenty Years Later: From Reluctance to Maturation,” India Review 17, no. 1 (2018): 161.

[10] “Guest Column | Nuclear No First Use Policy -,” accessed October 31, 2019, http://forceindia.net/guest-column/guest-column-b-s-nagal/nuclear-no-first-use-policy/.

[11] Shivshankar Menon, “Choices: Inside the Making of India’s Foreign Policy” (Washington D.C., U.S.A: Brookings Institution Press, 2016), 117.

[12] Dinakar Peri, “Should India Tinker with Its ‘No First Use’ Policy?,” The Hindu, August 23, 2019, sec. Comment, https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/should-india-tinker-with-its-no-first-use-policy/article29224507.ece.

[13] Peri.

[14] Franz-Stefan Gady, “Indian Navy Boomer Completes ‘First Deterrent Patrol,’” The Diplomat, accessed October 31, 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2018/11/indian-navy-boomer-completes-first-deterrent-patrol/.

[15] Harsh V. Pant and Yogesh Joshi, “Nuclear Rethink: A Change in India’s Nuclear Doctrine Has Implications on Cost & War Strategy,” The Economic TImes, August 17, 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/nuclear-rethink-a-change-in-indias-nuclear-doctrine-has-implications-on-cost-war-strategy/articleshow/70718646.cms; BS Nagal, “India’s Nuclear Strategy to Deter,” n.d.

*본 기고문은 전문가 개인의 의견으로, 서울대 아시아연구소와 의견이 다를 수 있음을 밝힙니다.