Lucía Rud (University of Buenos Aires/SNUAC)

Cinema is widely considered a national industry. For example, when people talk about the success of “Korean cinema,” they are referring to productions by Korean companies, supported by Korean public institutions, with Korean directors and actors, usually filmed in Korea. There is another perspective that considers cinema to be regional. For example, “Asian cinema” became a well-circulated term at international film festivals, in academia, and among popular moviegoers in the late 1980s (Khoo, 2021). On occasion, the tag Asian cinema was confined to action, martial arts, or horror films. With these blurred boundaries, the field of film studies describes Asian cinema as a specific mode of production and representation. But is it possible for ethnicity in cinema to extend beyond regional and national borders?

Only in the last ten years has Asianness become an explicit part of Hollywood. After a strong movement against the racist jokes told at the Academy Awards ceremony in 2016, along with the whitewashing of Asian characters in the mainstream films Aloha (2015) and Doctor Strange (2016), Hollywood started to be more receptive to Asianness (Magnan-Park, 2018). A movement in favor of incorporating Asian American protagonists began with the films Columbus (Kogonada, 2017), Searching (Aneesh Chaganty, 2018), Crazy Rich Asians (Jon M. Chu, 2018; Zhao, 2020), Always Be My Maybe (Nahnatchka Khan, 2019), and The Farewell (Lulu Wang, 2019). Previously, few US commercial films featured East Asian protagonists.[1]

The success of Asianness in the United States was confirmed by the Academy Awards bestowed on Minari and Everything Everywhere All at Once. These films are American in every sense, produced by the American companies Plan B and A24, respectively. But they are also profoundly Asian. The dialogue is spoken largely in Korean in Minari and in Mandarin and Cantonese in Everything Everywhere All at Once. These films highlight something that has existed for decades: an accented, non-national cinema that, though made by production companies and filmmakers outside of Asia, is somehow Asian (Naficy, 2001). But we should not be naïve: If Hollywood is making this Asian pivot—such as recognizing Parasite (Bong Joon-ho, 2019), the first foreign-language film to win the Academy Award for Best Picture—it is not because of a sudden self-consciousness regarding its representation of Asians but to retain its dominance at the box office (Magnan-Park, 2018). Nevertheless, it led to these questions: Can there be Asianness in non-Asian films? Are films made by the Asian diaspora part of Asian cinema?

Far from Hollywood, Argentinian cinema has been portraying its Asian communities for almost twenty years. Despite its economic difficulties, Argentina has a strong film industry. It produces more than 200 films a year, participates in international film festivals, and is recognized for its cinematic creativity. Its East Asian migrant population is relatively large. The Japanese community in Argentina, consisting of nearly 11,000 Japanese-born and 23,000 descendants, has been present since 1908. It is the third largest Japanese community in South America, after Brazil and Peru. The Korean community in Argentina was established in the 1960s and was strengthened in 1985 with a bilateral agreement between the two countries; there are currently 7,000 Korean-born and 20,000 descendants in Argentina. The Chinese community (both mainland and Taiwanese) has had a greater presence in Argentina since the 1980s. At more than 100,000 people, it is the fifth largest migrant community in Argentina.[2] The ethnic composition of Argentina (which, like that of other Latin American countries, is very diverse) is only occasionally reflected on the screen, where white actors are strongly favored. Among Asian Argentinian actors, the filmographies and TV appearances of Chang Sung Kim and Ignacio Huang are particularly relevant.

Several films link Argentina with East Asia. Probably the most well known is Wong Kar Wai’s Happy Together (1997). Also worth mentioning is the documentary Good Light, Good Air (Im Heung-soon, 2021), about the parallel between the Gwangju massacre and the mothers of Plaza de Mayo in Argentina, as well as the romantic comedies New Year Blues (Hong Ji-Young, 2021) and the fantasy drama If Cats Disappeared from the World (Akira Nagai, 2016). Among the Argentinian productions about the Asian-Argentine connection are La chica del Sur (José Luis García, 2013), De acá a la China (Federico Marcello, 2017), and Shalom Taiwan (Walter Tejblum, 2019); films about the East Asian migration in Argentina such as Una canción coreana (Gustavo Tarrío and Yael Tujsnaider, 2014), Nueva de Fujian (Analía Orfila, 2013), El futuro perfecto (Nele Wohlatz, 2016), Samurai (Gaspar Scheuer, 2013), Arribeños (Marcos Rodríguez, 2015), and 50 Chuseok (Tamae Garateguy, 2018); and even a sci-fi-thriller, Mujer Conejo (Verónica Chen, 2013). In addition, Argentina has participated in the Looking China Youth Film Project, an initiative of the Huilin Foundation and the Academy for International Communication of Chinese Culture of Beijing Normal University.

This article addresses the trajectory of four Argentine Asian filmmakers: Juan Martín Hsu, Cecilia Kang, Daniel Kim, and Esteban Bae (Youn-suk Bae), who can be considered not only part of Argentine cinema but also part of Asian cinema.[3] Although these filmmakers’ work is Argentinian in the sense that their production companies are Argentine and some of their films were produced with the support of Argentina’s National Institute of Cinema and Audiovisual Arts (INCAA), they can be considered examples of an accented cinema, a cinema with transnational aspects. Hamid Naficy defines “accented cinemas” as those of exile and diaspora, as opposed to the nonaccented “universal” dominant cinema. Naficy states that the accent emanates not from the accented speech of the diegetic characters but from the displacement of the filmmakers and their artisanal modes of production (Naficy, 2001).

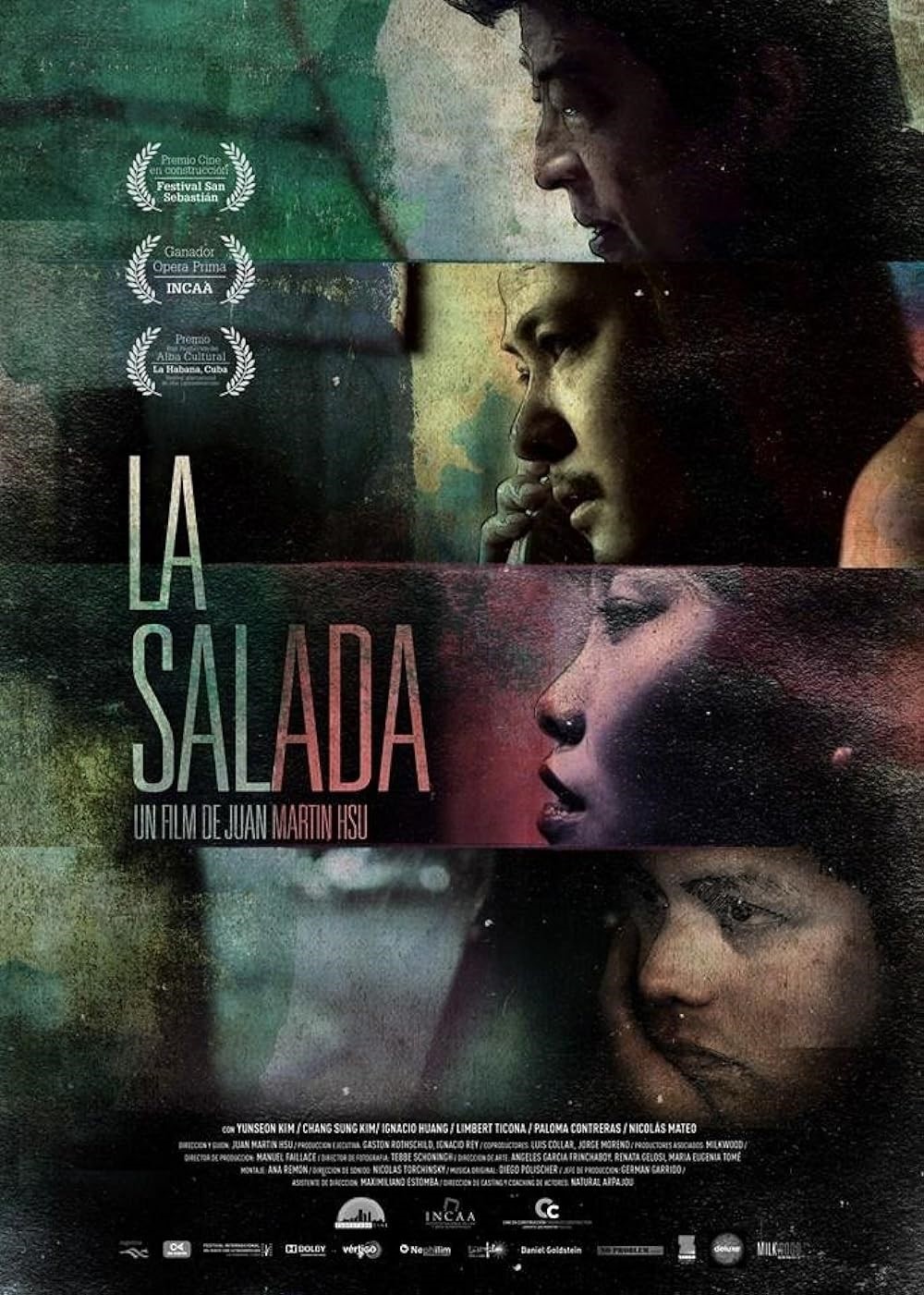

Juan Martín Hsu, the son of a Taiwanese mother and a Chinese father based in Buenos Aires, was born in Argentina in 1979. He studied image and sound design at the University of Buenos Aires. His first feature film, La salada (2014), won the Film in Progress Prize at the San Sebastián Film Festival (2013) and was shown at numerous other festivals, including the 39th Toronto Film Festival and Latin Horizons of San Sebastián. In 2015 he directed Diamante Mandarín, the short film version of the feature Historias Breves X, with support from Muralla Dorada International Media Company (chaired by Ana Chen) and produced by Meahogo, Zebra films, and Puente. In 2021 his hybrid documentary (which includes short fiction within the main documentary) La luna representa mi corazón premiered at the Visions du Réel International Competition.

Despite being Argentine productions, Hsu’s three films contain mostly non-Spanish dialogue. La salada, which takes place in a well-known clothing market, tells the stories of Chinese and Korean migrants and Bolivians, so the dialogue consists of Mandarin, Korean, and Quechua. Three intertwined stories are told: that of Korean merchant Kim and his daughter Yunjin; that of Huang, a lonely young Taiwanese insomniac and movie buff; and that of two Bolivians, Bruno and his uncle, who have recently arrived in Buenos Aires. Casting is a key aspect of Hsu’s films, and he states that the actors must speak the language of their characters (however, in the case of La salada, Chang Sung Kim’s Korean language skills were criticized by the local Korean community, which didn’t consider the accent credible) (Lee, 2016).

Diamante Mandarín depicts events inside a Chinese supermarket in Buenos Aires in December 2001. That was a time of deep political, economic, social, and institutional crisis, fueled by a popular revolt that led to the resignation of Argentina’s president, Fernando de la Rúa. This movement included the looting of supermarkets, often owned by Chinese and Korean immigrants. In the Argentine collective memory, the events of December 2001 took place in the streets, but Diamante Mandarín takes another point of view and shows the confinement of those seeking refuge inside a store. Eight Chinese individuals (a couple and their two young children, the wife’s father, the husband’s younger sister, another relative, and a family friend) barricade themselves in the store after watching the looting on the TV news. During the nights of uncertainty, conflicts among these characters are glimpsed: the couple discusses the possibility of sending their daughter to China; the head of the family exerts pressure on his sister (the flip side of respect for elders); relatives in China worry about what is happening on the other side of the world; they play a game of mahjong to pass the time. These conflicts and customs typical of the lives of Chinese immigrants in Argentina are not shown with a didactic intention; there are no overexplanations.

Hsu’s 2021 documentary La luna representa mi corazón shows his relationship with his mother, who lives in Taiwan and whom the director hadn’t seen in ten years. It is a family journey that unravels the most difficult parts of the family’s history: the father’s murder, the grandfather’s torture, the mother’s hard life. It is a documentary of permanent search. In some cases, the director filmed fixed shots for hours until he found some minimal fragments that he considered significant. The documentary frames the family’s story within the history of the two countries, showing a continuity between Argentina’s military governments (in the 1970s) and Taiwan’s dictatorship and the idea of migration as a way to escape. It is a very personal film, yet it also tells a larger story of migration and connections (and disconnections) between Taiwan and Argentina.

Cecilia Kang was born in Buenos Aires in 1985 to a Korean family that had migrated shortly before her birth. She studied film directing at the National School of Cinematographic Experimentation and Production (ENERC). Her first feature film, Mi último fracaso (2016), is a documentary about the various modalities of the feminine among different generations of the Korean community in Argentina, the sentimental relationships they establish, the cultural duality, and their affective and loving bonds. It was made with only a small technical team and with the support of ENERC in post-production; the Korean Women’s International Network (KOWIN) Argentina financed the director’s filming in Korea. The film was presented at the 18th BAFICI 2016 (in competition) and at the Mar del Plata International Film Festival 2016 (Panorama section), among other national festivals, and it was shown at the Argentine embassy in the Republic of Korea. Kang currently has two works in production: her second documentary, Partió de mí un barco llevándome, is a feature about comfort women. And in pre-production is Hijo mayor, a feature film about her family’s migration to Argentina during the 1980s.

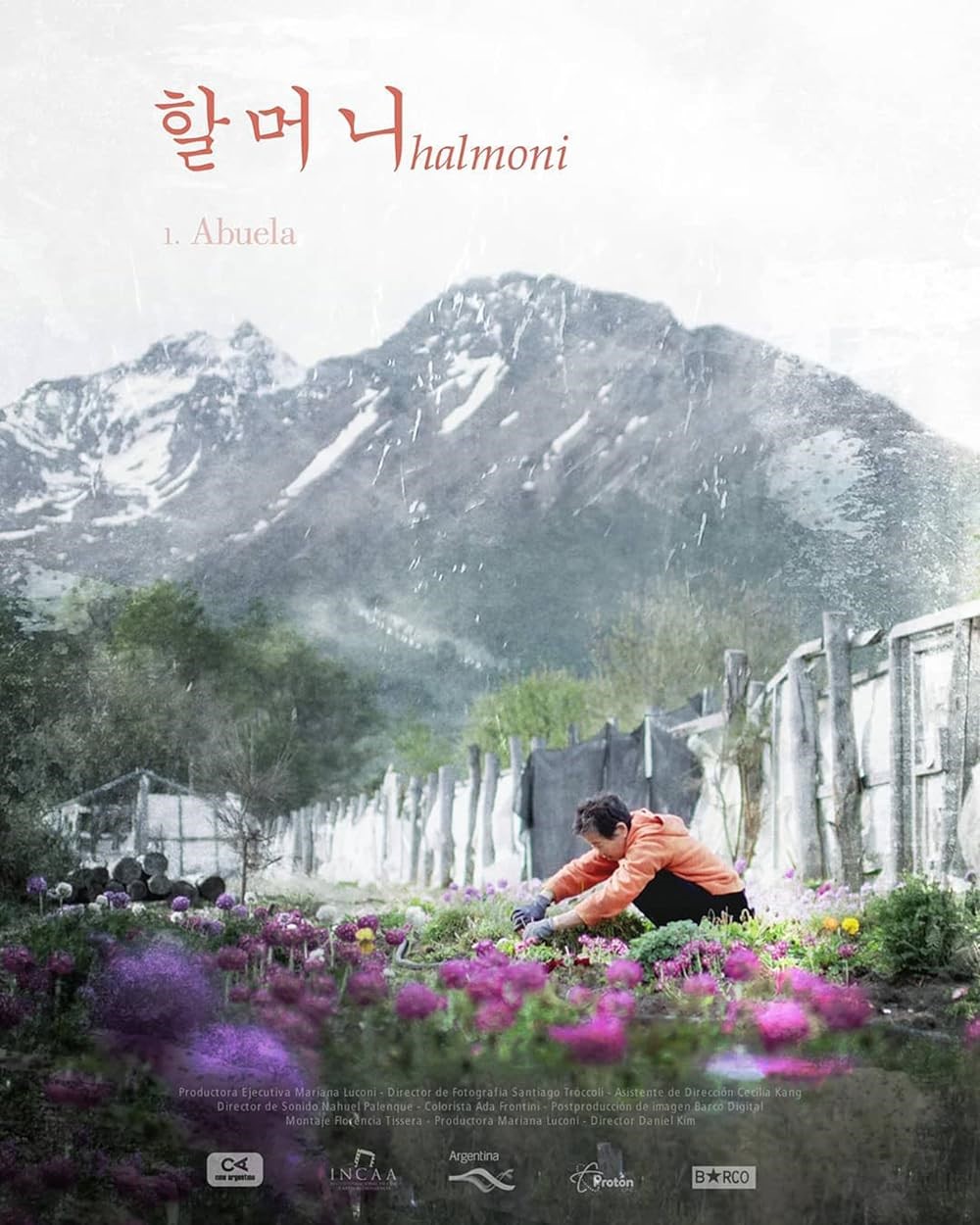

Daniel Kim was born in 1990 in Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego (an almost mythical place that also appears in Happy Together and La chica del sur), and studied film editing at ENERC. His documentary Halmoni tells the story of his family, who arrived in Ushuaia in 1974, and is mainly about his grandmother, Jo Ok Sim. It is a story of roots and uprooting, and the land plays a major role. Kim’s grandfather intends to plant lettuce in the hostile land, and one theme is repeated throughout the film: “the place where you can eat and live, that will be your home.” There is a heavy use of personal documents and home movies, following a style similar to that of Tarnation (Jonathan Caouette, 2003) or As I Was Moving Ahead, Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty (Jonas Mekas, 2001). The filmmaking process was a long one: Kim started in 2013, and the film premiered in 2019.

The dialogue of Halmoni is spoken mostly in a variant of Korean that marks the diaspora by incorporating Spanish words. In particular, the names of plants are in Spanish—achicoria, lechuga, amapola, orquídea, potus, suculenta, ciboulette, araucaria, lazo de amor: “This is a trébol rojo, red color. I do not remember what they are called in our country. The name was different.”

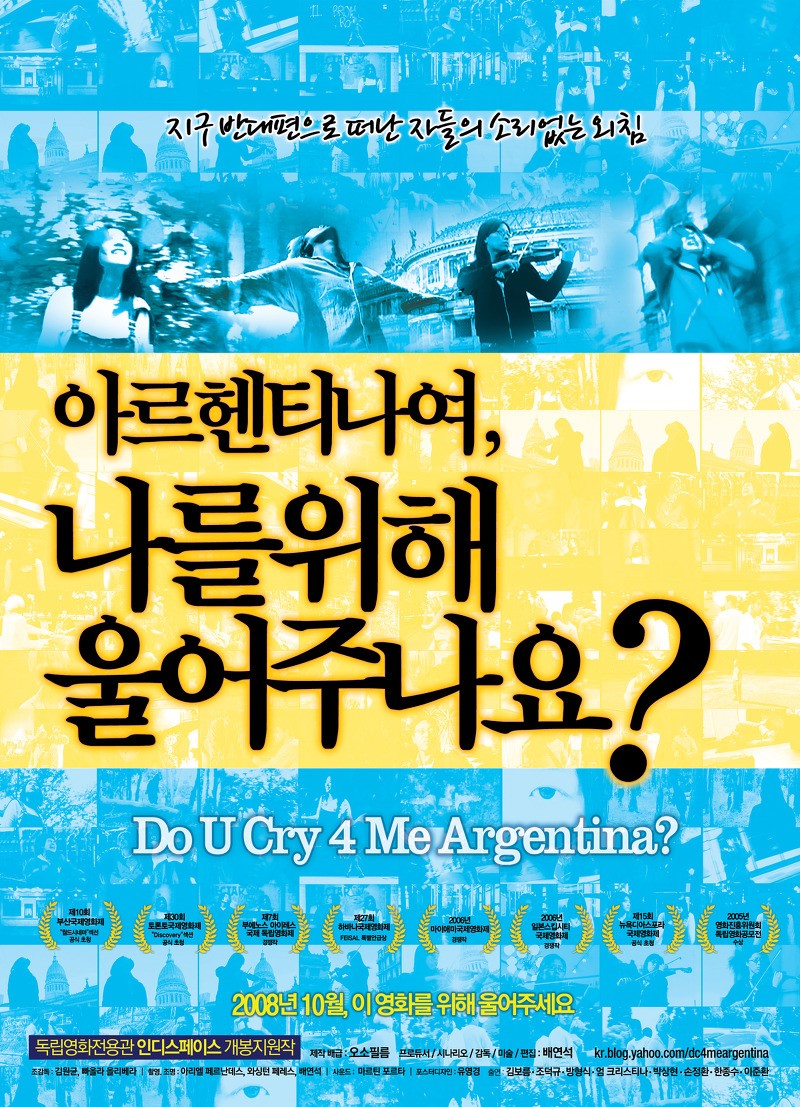

One film that stands out for anticipating the topic of this paper and as a historical document of an era is Do u cry 4 me Argentina? (2005). It was scripted, directed, produced, and edited by Bae Esteban Youn-suk (born in Seoul in 1973), who lived in Argentina from 1986 to 2006. He studied marketing at the University of Palermo and studied film and TV at Taller Imagen y Sonido School. The film depicts the cultural and national mismatches experienced by the 1.5 generation—an in-between generation consisting of children who migrated to Argentina at school age, without the usual assimilation of the second generation or the rootedness of the first generation. Although the film refers marginally to relations with Argentines (and other Latin Americans), the focus is on links within the community: generational tensions, the obsession with work and money, and the conflicts between those who have become rich (often by exploiting their compatriots, like Orange and his father, who press for rent payments and merchandise controls) and those who have not (who turn to crime as a form of revenge). Far from being satisfied with documenting a community and a particular generation, the film undertakes a stylistic search, with aesthetic allusions to contemporary Hollywood (American Beauty, Sam Mendes, 2000; The Mask of Scream, Wes Craven, 1996), the crossing of genres (typical of Korean cinema, with characters who offer comic relief, musical fragments, and aspects of the gangster genre), and a certain social realism typical of Argentine cinema.

The fiction is framed with information about the community. At the beginning, a plaque informs the audience that, between 1986 and 1991, more than 20,000 Koreans arrived in Argentina. Toward the end of the film, Argentine newspaper headlines in the Korean language are displayed: “The assaults by hooded thieves on Koreans continue”; “Again, 3 assailants in Koreans’ house. It is assumed that they knew well the movements of the interior”; “Armed Argentine robbers act at any time of the day”; “There was a kidnapping and the victim was beaten. The perpetrators were Koreans”; “A young Korean man was murdered in his apartment.” Beyond being a fiction framed in genre cinema, there is an explicit intention to function as a record of reality.

These films have the simultaneous capacity to say something about Asia and something about Argentina. What does it mean to be Asian in Argentina? In films about the 1.5 generation and the second generation, the relationship with the parents’ country of origin is in tension, and there is a strong quest for identity. Unlike films made in the United States or Europe, these films contain a hint of failure associated with migration: China, Taiwan, and South Korea are currently much richer than Latin America. This is explicitly stated in Halmoni, where the family members who stayed in Korea say to Grandmother Ok:

- People who went to the United States suffered and suffered but made good money.

- There are people who went and succeeded. There are people who did not. It all depends on what is the parameter to measure success.

- It’s no use, you have to earn money.

At the same time, there is a sort of vindication. The Asian Argentine population was highly stigmatized in the 1980s and 1990s, but today, with the rise of Asia, Asians are experiencing a growing popularity in Latin America. At the same time, in Asia there is often a lack of interest in the lives of Asians in Latin America. Most of the films mentioned were neither co-produced with Asian counterparts nor exhibited in Asia; the exceptions are Do u cry 4 me Argentina? which can be found in many of the Korean over-the-top (OTT) services, and La luna representa mi corazón, co-produced by the Taiwanese production company Moolin Films (木林 !映画) and with the support of the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute.[4]

It is worth noting that if these art house projects are possible, it is due to the existence of broad audiovisual activity in Argentina, where there are film studies programs (such as at the University of Buenos Aires and ENERC) and financial support for audiovisual production from the INCAA—in the case of Halmoni and the three films made by Hsu.

Currently, there is a profound crisis in Hollywood’s global audiovisual sector. The existence of cinema as we have known it for more than a century is in jeopardy, while the audiovisual sector is growing exponentially. Film in celluloid no longer exists, and the current strike by screenwriters and actors in the United States has led to fears that, in the near future, there will be no need for screenwriters, directors, or actors, as their contributions will all be generated by computers. I believe that part of the answer to this crisis in cinema is to pay attention to what is happening in the world outside of Hollywood, in small films without artifice, with few digital resources, and with very limited budgets but with a strong storytelling drive.

About the Author

Lucía Rud (lrud@filo.uba.ar, luciarud@gmail.com) is

a film researcher from the University of Buenos Aires/National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET). She studied arts, film, and theater at the University of Buenos Aires and cinema direction and production at Buenos Aires Comunicación College. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Buenos Aires and holds an M.A. in cultural diversity from Tres de Febrero University. She has been researching the transnational cultural ties between Argentina and South Korea for the past seven years. Lucía was a visiting scholar at the SNUAC-SNU (spring 2023).

References

- Fuller, Karla Rae. 1997. Hollywood goes Oriental: CaucAsian performance in American cinema. Evanstone: Northwestern University Press.

- Khoo, Olivia. 2021. Asian cinema: A regional view. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Lee, Ana Paulina, and Anna Kazumi Stahl. 2016. “Memory and migration.” Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas 2, no. 1–2, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1163/23523085-00202002.

- Magnan-Park, Aaron Han Joon. 2018. “Leukocentric Hollywood: Whitewashing, Alohagate and the dawn of Hollywood with Chinese characteristics.” Asian Cinema 29, no. 1, 133–162.

- Naficy, Hamid. 2001. An accented cinema: Exilic and diasporic filmmaking. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sakai, Naoki, and Ge Sun. 2019. Universality and particularity: What is Asianness? Berlin: Archive Books.

- Zhao, Yikun. 2020. “Crazy Rich Asians: When representation becomes controversial.” Markets, Globalization & Development Review 4, no. 3.

[1] One of the few exceptions is The Joy Luck Club (Wayne Wang, 1993). On Asian representation in Hollywood, see Park, Jane Chi Hyun. Yellow future: Oriental style in Hollywood cinema. University of Minnesota Press, 2010; Lee, Robert G. Orientals: Asian Americans in popular culture. Temple University Press, 1999; King, Homay. Lost in translation: Orientalism, cinema, and the enigmatic signifier. Duke University Press, 2010.

[2] There is no official information about the number of Asian citizens in Argentina (there is no “Asian” category in the national census). Therefore, the numbers provided here are estimates.

[3] Other Argentine Asian filmmakers include Verónica Chen and Tamae Garateguy, among others.

[4] These films were exhibited at Asian film festivals: Do u cry 4 me Argentina? in 2005 at the Busan IFF and the Dongpo Film Festival in Seoul, and La luna representa mi corazón at the 2022 Taiwan International Documentary Film Festival.