Mohammad Belayet Hossain (Chittagong Independent University, Bangladesh)

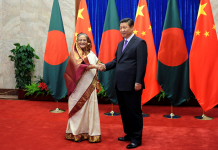

Bangladesh and ‘One Belt, One Road’ Project of China

To become a developed country and achieving sustainable development goals, the current government of Bangladesh became a signatory in order to obtain a better deal for the country. China’s “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) is a development strategy about building partnerships and infrastructure to boost trade among regional countries with the creation of infrastructure such as ports, railways and expressways including energy and information technology. The future investment will flow into the education, food and beverages, recreation, tourism, hotel and healthcare sectors. Bangladesh stands out as an attractive BRI destination due to an investment environment, which offers various opportunities and low levels of risk. In recent years, Bangladesh has seen remarkable progress in outward direct investments (ODIs) from China. It has been reported that the flow of investment from China to Bangladesh is expected to spread into more sectors; many Chinese firms are likely to invest in other promising sectors in Bangladesh.

The Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar economic corridor – multi-modal connection via combination of sea and land transport

ⓒ DIVERSE+ASIA

Sovereignty of Bangladesh and the Chinese Investments in BRI

There should be a raising concern of ‘Bangladesh’s Sovereignty’ about how China’s investments would influence the socio-cultural and demographic changes in Bangladesh. China’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative has definitely raised some political and economic concerns not just in Bangladesh but also throughout the coverage of the scheme globally. While it may not be clear at this point in time how and to what extent all these huge investment schemes will influence socio-cultural and demographic changes in Bangladesh; the impact of mega infrastructural projects on the dynamics of socio-cultural and demographic perspective is perhaps best reflected by the Chinese investments in Africa. As long as there is a credible Bangladeshi component in the participation or ownership of these huge development projects, I believe the ‘Bangladesh’s Sovereignty’ issue could be protected.

Even though the Government may be confident enough to assure that stronger Chinese investments will not taint Bangladesh’s sovereignty, but there is anxiety about how China’s investments would influence the wetlands; mangroves; ocean creatures that are heritage; damages to the long standing fishing business; and the effects on the domestic estate marketplace to meet the domestic demands. Critics have cautioned that over-concentration of Chinese investments in Bangladesh may turn wrong, given any probable disruptions in China’s domestic economy. Moreover, the OBOR has spurred much speculation among policy-makers and scholars around the globe. In fact, many have dubbed it as China’s own “Marshall Plan”.

Nonetheless, will Chinese investment actually affect the “national sovereignty” of Bangladesh or poses any threat to “Bangladesh’s Sovereignty”? The proponents of BRI argue that Chinese investments should not be viewed as a racial and international conflict; rather should be seen as a positive contribution to resolve the basic necessities. The Chinese investments raise aggregate investment demand and upon completion, the services or industrial output from the investment project will boost the economy’s production capacity and its growth potential. Bangladesh can also become a cosmopolitan country and the BRI will help to build up the country in this regard. However, since becoming a member of the BRI in 2016, both countries have signed twenty-seven agreements for investments and loans worth USD 24 billion; but to the best of the author’s knowledge, these agreements are not yet disclosed to the public. The agreements are not even available on the official Chinese Belt and Road Initiative website and Bangladesh government’s website. So right now, it is not possible to comment on the matter of Bangladesh’s sovereignty in relation to BRI i.e. whether there is any provision in those agreements, which could violate the sovereignty of Bangladesh.

In such a case, there should be emphasis that every infrastructure projects developed by Chinese investors in BRI should take Bangladesh’s socio-political culture into account and ensure that ‘Bangladesh’s sovereignty’ is protected. To protect the sovereignty, along with the local Chinese Chambers of Commerce, the Bangladesh Chambers of Commerce should also be involved in every China investment projects; so as to make certain that the Chinese government is more conscious about the local needs or development goals of Bangladesh.

Source: AP Photo

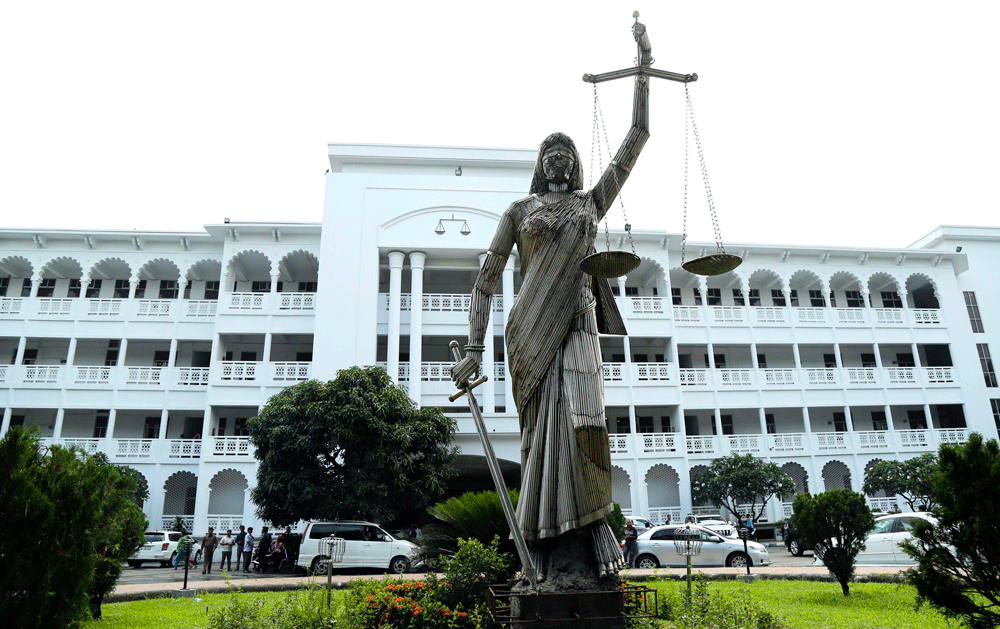

The Constitution of Bangladesh and Protecting Sovereignty from Chinese Investments

Furthermore, as Bangladesh is already a signatory of the BRI, already signed agreements between parties and/or there will be various agreements or treaties that shall be signed between two countries. In this connection, it is necessary to look into the Constitution of Bangladesh, whether there is any provision exists to protect the sovereignty of the country from foreign investments or BRI. Article 145A of the Constitution states as follows:

“All treaties with foreign countries shall be submitted to the President, who shall cause them to be laid before Parliament:

Provided that any such treaty connected with national security shall be laid in a secret session of Parliament.”

As it appears from the above, Article 145A requires all international treaties should be presented before the parliament. What lacks this article 145A is the uncertainty as to the function of the parliament. It seems that parliament cannot do more than discussing the international treaty. The wording of Article 145A also suggest that the parliamentary members have authority to consider all kind of investment treaties; however, it lacks to provide any guidance on what set of issues or factors need to be considered to protect the sovereignty and national security of Bangladesh. For instance, in Australia Section 22(2) of the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Regulation 2015 empowers the Treasurer with broad discretion to apply ‘national-interest test’ to block any FDI proposal, which goes against the national interest and security. The Treasure considers sovereignty, national security, competition, Australian Government Policies, impact on the Australian economy and community and investor character. Therefore, such a complete rejection of parliamentary control over international treaty is not justifiable on any ground at all. Thus, by amending this Article, the Parliament should be given authority to approve or refuse any international treaty considering sovereignty, national interest and security.

Moreover, the Article also states that “if an international treaty relates to the question of national security, that treaty will be discussed in the secret session of the parliament”. So far, only one treaty titled ‘The Ganga Water Sharing Treaty’, 1966 placed before the parliament in 1997 for discussion and debates by the members of the parliament. However, this Article does not define the phrase ‘secret session’ anywhere in the constitution. In such a case, it appears to be an incomplete provision of the Constitution, raising new issues and creating further difficulty than it solves.

Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) between Bangladesh and China

The People’s Republic of Bangladesh signed the BIT with the Government of the People’s Republic of China in 1996, which is still in force. Surprisingly, the text of this BIT has not yet been made public due to unknown reason. Therefore, it is not possible to scrutinize the legal obligations of both countries, especially Bangladesh. It could be questionable about the non-availability of this BIT, even it is not available on the UNCTAD website.

Cases Regarding Protecting Sovereignty of Bangladesh

In Chaudhury and Kendra v Bangladesh and BNWLA v Government of Bangladesh and others, the Supreme Court held that “the courts in Bangladesh cannot enforce treaties, even if ratified by the state, unless these were incorporated in the municipal laws”. Regarding the application of international instruments, in the case of BNWLA v Government of Bangladesh and others, the Supreme Court declared that “when there is a gap in municipal law in addressing any issue, the court may take recourse to the international conventions and protocols until the national legislature enacts laws in this regard”. However, in the case of Bangladesh and others v Hasina, the Supreme Court further strengthened by saying that “the courts would not enforce international human rights treaties, even if ratified by Bangladesh, unless these are incorporated into municipal laws”.

Source: AP Photo

Sovereign Right of Bangladesh Through International Instruments to Regulate Chinese Investments in BRI

After the end of the colonial era, when states began to function as politically independent and sovereign entities, they realised that one of the most important attributes of state sovereignty was economic sovereignty. Without this, political sovereignty was not complete. Asserting economic sovereignty meant having control over the economic activities of both juridical and natural persons conducting business within the country, whether nationals of that country or foreigners. When the country concerned wished to embark on a policy of economic development, one of the first initiatives it had to take was to consider harnessing its natural resources in accordance with its economic policies. It therefore became necessary for these states to assert sovereignty over the natural resources of the country and require that foreign individuals and companies comply with the new policy adopted by the state. However, developed countries whose nationals had gone overseas to invest and do business, resisted attempts to impose national law on foreigners. They argued that existing concessions and contracts had to be honoured under international law. It was at this juncture that the concept of permanent sovereignty over natural resources was introduced in international law.

Consequently, a resolution was introduced in the UN General Assembly to this effect and was passed by an overwhelming majority of states. Paragraphs 1 and 2 of the famous 1962 UN General Assembly Resolution on the Permanent Sovereignty over Natural Resources state:

The right of peoples and nations to permanent sovereignty over their natural wealth and resources must be exercised in the interest of their national development and of the well-being of the people of the state concerned.

Moreover, the UN General Assembly adopted the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States of 1974, which outlines the sovereign right of the host state to control FDI in a more concrete manner. Article 2 states:

Every state has the right to exercise full permanent sovereignty, including possession, use and disposal, over all its wealth, natural resources and economic activities; as well as to regulate and exercise authority over foreign investment within its national jurisdiction in accordance with its laws and regulations and in conformity with its national objectives and priorities.

The above-mentioned right was reinforced and strengthened through a 1986 resolution of the UN General Assembly on the right to economic development of states. It recognises the inalienable right of the host state to full sovereignty over all their natural wealth and resources; and also have the right to formulate appropriate national development policies. Moreover, according to customary law the entry of foreign capital in the form of FDI is always subject to state sovereignty. It recognizes that entry of FDI is entirely a sovereign prerogative of the state and this is a right, which is unlikely to be given up.

Source: UN Photo

It can be drawn from the above discussion that the host state, such as Bangladesh has complete right to impose conditions on FDI (including Chinese investments in BRI) through legal means and ways according to which the investment should be made; the planning and environmental controls; the manufacturing plant should be subject to; the nature of the capital resources brought in from outside the state should be; the circumstances of the termination of the foreign investment should be and so on. Moreover, this sovereign right is unlimited, which is also established by the Privy Council in the following words:

One of the rights possessed by the supreme power in every state is the right to refuse the alien to enter that state, to annex what conditions it pleases to the permission to enter it and to expel and deport from the state, at pleasure, even a friendly alien, especially if it considers his presence in the state opposed to its peace, order and good government, or to its social and material interests.

The unlimited right of Bangladesh to regulate Chinese FDI in BRI is also established by the decisions of various cases. In Schmidt v Secretary of State for Home Affaires, Lord Denning observed that in common law, an alien has no right to enter into the country except by leave of the Crown; and the Crown can refuse leave without giving any reason. Also in Electronica Sicula S.p.A (ELSI) Case, Judge Oda held a proposition that

When businesses being incorporated in one country undertake commercial transaction through local companies of another country, they be treated as legal entities of that country and would be subject to local laws and regulations. Thus foreigners may have to accept a number of restrictions in order to gain the advantages of doing business through local companies.

Moreover, Ralston observed similarly that “a nation may by general provisions exclude a certain class of individuals entirely or place limitations upon their admission subject to the duty to inform them of the special conditions of entry when they seek admission”.

Therefore, from the above discussion it can be concluded that Bangladesh has the sovereign right of regulating or control Chinese FDI in BRI, which can be exercised by introducing specific provision in general; or in particular in the legal and policy regime for FDI; or any other related law having a linkage to the investment operation.

What the Government of Bangladesh Should Do?

As it appears from the above discussion that there is no statutory provision as regards the ratification of treaties, nor has the Constitution mentioned any clear provision for treaty implementation. Therefore, the international treaties signed and ratified by the Government of Bangladesh would require implementing legislation or constitutional amendment to apply them within its domestic jurisdiction, if:

(a) it involves alteration of the existing law;

(b) confers new powers to the executive;

(c) imposes financial obligation to the citizens;

(d) affects the right of citizens; and

(e) involves alienation or cession of any part of the territory of Bangladesh.

How smoothly international instruments would be applied in the legal system, is a question of utmost national interest. The policymaker needs to realise that the government institutions and individuals have both rights and obligations under international law. Consequently, it is necessary to draw a comprehensible picture for regulatory regime in relation to the application of international law in Bangladesh.

The Government of Bangladesh must have national policies for safeguarding its sovereignty, national interest, and internal security in BRI. Relevant factors for consideration should be whether the text of a treaty undermines its sovereignty, complies with its national policies pertaining to defence, security, the environment, heritage, revenue, and so on.

Author Introduction

Mohammad Belayet Hossain (galib@ciu.edu.bd) is

currently working as Assistant Professor in School of Law, CIU. Mr Hossain is a Ph.D. (candidate) at Universiti Utara Malaysia and his thesis is on FDI laws of Bangladesh and Malaysia. He completed LLM in Commercial and Corporate Law from University of London, UK; LLB (Hons.) from University of Northumbria, UK and Diploma in Law from University of London, UK. Before joining CIU he was working as Legal Advisor at Roots 99 Limited and New Horizons CLC of Bangladesh in Dhaka. He also worked as a Lecturer at City University, Bangladesh and St. Georges College, UK. His work experience includes working as a Project Manager for Diwan Amiri (Govt of Qatar), Qatar and was in charge of a research team based in UK. He was employed for more than eight years as a Leading Library Assistant (LLA) at the British Library, UK while pursuing Law degrees. He worked as a Research Assistant at Leonard & Co. Solicitors, UK. Mr Hossain is a notable author with a number of publications nationally and internationally. He has also published articles in various national and international journals. Mr Hossain is a reviewer in Beijing Law Review. Mr Hossain is a member in the Bangladesh Bar Council, the British Library (UK), the National Archive (UK), Cambridge University Library (UK), Library of the British Parliament (UK), Natural History Museum Library (UK).

References

Books

- Bath, Vivienne and Nottage, Luke. Foreign investment and dispute resolution law and practice in Asia, (Routledge, 2011).

- Sherif, Seid H. Global regulation of foreign direct investment, (Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2002).

- Sornarajah, Muthucumaraswamy. The international law on foreign investment. (Cambridge University Press, 3rd ed., 2010, 55).

- Subedi, Surya P. International Investment Law: Reconciling Policy and Practice, (Hart Publishing, 2008).

Articles

- Abdin, Joynal, ‘Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Bangladesh: Trends, Challenges, and Recommendations’, International Journal of Sustainable Economies Management (IJSEM) 4, no. 2 (2015), 36-45.

- Ahmed, Nazneen, and Nathan, Dev, ‘Improving wages and working conditions in the Bangladeshi garment sector: The role of horizontal and vertical relations’, Capturing the Gains (2014).

- Ang, James B, ‘Do public investment and FDI crowd in or crowd out private domestic investment in Malaysia?’, Applied Economics 41, no. 7 (2009), 913-919.

- Bengoa, Marta and Sanchez-Robles, Blanca, ‘Foreign direct investment, economic freedom and growth: new evidence from Latin America’, European journal of political economy 19, no. 3 (2003), 529-545.

- Chowdhury, M, Ahmed, Razu and Yasmin, Masuma, ‘Prospects and Problems of RMG Industry: A study on Bangladesh’, Prospects 5, no. 7 (2014), 103-118.

- Clark, C. and Kanter, S, ‘Violence in the Readymade Garments (RMG) industry in Bangladesh’, Center for international and comparative studies. University of Michigan 3, no. 1 (2010), 6-12.

- Duasa, Jarita, ‘Malaysian foreign direct investment and growth: does stability matter?’, Journal of Economic Cooperation Among Islamic Countries 28, no. 2 (2007).

- Hossain, Mohammad Belayet and Rahi, Saida Talukder, ‘International Economic Law and Policy: A Comprehensive and Critical Analysis of the Historical Development’, Beijing Law Review 9, no. 04 (2018), 524.

- Hossain, Mohammad Belayet, ‘Evolution of the law of foreign investment on expropriation of foreign property’, International Journal of Entrepreneurship & Development Studies (IJEDS), vol 5, no-1, Jan 2017, pp 53-66.

- Hossain, Mohammad Belayet, ‘The notion of corporate responsibility of the multinational enterprises (MNEs)’, Lex-Warrier: Online Law Journal, vol 8, issue 5, 2018, 228-235.

- Hossain, Mohammad Belayet, ‘Fleshing out the provisions for protecting foreign investment’, Yustisia Jurnal Hukum, vol 7, no. 3, Sep-Dec, 2018, 406-427.

- Hossain, Mohammad Belayet, ‘International efforts to regulate foreign investment and Multinational Enterprises (MNEs),’ Lex-Warrier: Online Law Journal, vol 9, issue 9, 2018, 401- 414.

- Hussain, Abdullah Al-Manzur and Mohammad Belayet Hossain, “Commercial Dispute Settlement in Bangladesh: Practice, Challenges and Way Forward,” Bangladesh Research Foundation Journal, vol 7, no 2.

- Hussain, Mohammed Ershad and Haque, Mahfuzul, ‘Foreign direct investment, trade, and economic growth: An empirical analysis of Bangladesh’, Economies 4, no. 2 (2016), 7.

- Kishoiyian, Bernard, ‘The utility of bilateral investment treaties in the formulation of customary international law’, Nw. J. Int’l L. & Bus. 14 (1993), 327.

- Salem-Haghighi, S, ‘MAI and BITs: A Comparative Study’, Research Paper, Institute of Comparative Law Montreal (1998).

- Soloman, Lewis D., and David H. Mirsky, ‘Direct Foreign Investment in the Caribbean: A Legal and Policy Analysis’, Nw. J. Int’l L. & Bus. 11 (1990), 257.

- Uddin, M. and Chowdhury, S, ‘The impact of public investment and economic growth in Bangladesh’, International Journal of Development and Emerging Economies, 3(2): (2015), 72-97.

- UNCTAD, Foreign Direct Investment and Performance Requirements: New Evidence from Selected Countries (2003).

Cases

- Schmidt v Secretary of State for Home Affaires [1969] 2 Ch 149, 168.

- Electronica Sicula S.p.A (ELSI) [1989] ICJ Reports 15, 90.

- Chaudhury and Kendra v Bangladesh [2008] 29 BLD (HCD) 2009, ILDC 1515.

- BNWLA v Government of Bangladesh and others [2009] 14 BLC (HCD) 703.

- Bangladesh and others v Hasina [2008] 60 DLR (AD) 90.