Ji-in (Magdalena) Seol (SNUAC)

The changing climate is poised to create a wide array of economic and social risks over the next three decades. Climate science tells us that warming over the next decade is already locked in due to past emissions, suggesting that rising socioeconomic impacts are a virtual certainty around the world. Increased temperature, which may be welcomed in some places of the world, is only part of the consequences of climate change. More importantly, it affects rainfall patterns, droughts in mid to low-lying areas, decreased productivity of cereal crops, a rise in sea levels, the loss of islands and wetlands, more frequent and intense storms and flooding, the disappearance of species, the spread of infectious disease, and the more. In all, climate change poses systemic risks.

The nature of such systemic risks may be categorized into three types: physical risks (physical effects, damages and losses in hard infrastructure); transition risks (costs and changes in valuation arising from and during the transition to a low-carbon economy); and liability risks (arising from those seeking compensation for losses suffered from the physical or transition risks)1). Among these, physical risks, notably, are already present and growing around the world. Countries with lower per capita GDP levels are generally more exposed to these risks; its global socioeconomic impacts could be substantial.

From science to economics and politics

There lies complexity behind those risks. The science on climate change has been fairly clear – that the earth will eventually warm to what could be a catastrophic degree that many will come to regret. Scientists predict that severe consequences are more likely to occur when global average temperature increases by more than 2 degrees C, which equals approximately 450 parts per million (ppm) in CO2-equivalent terms. We are already on a path to more than double the greenhouse gas concentrations, approximately 1,000 ppm, by the end of this century. The anticipated damage is grave.

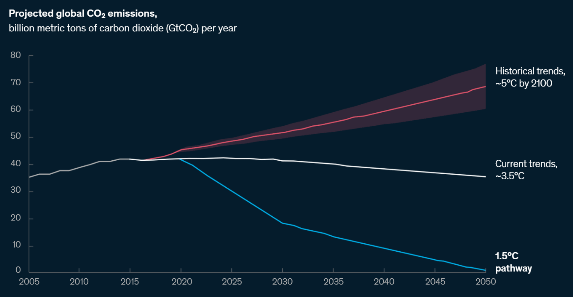

Avoiding the damage by cutting greenhouse gas emissions is neither cheap nor easy. From a purely economic perspective, the cost of achieving the 450ppm target will be significant, although it is not necessarily unwarranted. Economic analysis into the very target reveals that while it may be “very difficult” but “not impossible.” Holding warming to 1.5 degrees C above preindustrial levels could limit the most dangerous and irreversible effects of climate change. The next decade will be critical, and it will require major business, economic and societal shifts, each enormous in its own right with intricate interdependencies. This leads another layer to the complexity of the challenge: moving from economics to politics.

The two fundamentals of the spatial (the dilemma of the “global commons”) and temporal (the damages are linked with concentrations, not the emissions per se, and thus the accountability issue) of climate change present political challenges. Especially in the international, or global, scene, the fiendishly complicated politics of climate change have held back progress for long, in particular the once strict distinction between developed and developing countries. Now that this distinction has been removed in Paris, and with new leadership in the U.S. reclaiming its commitment, the chances of moving towards a meaningful global political coordination seem to be on a positive note; however, the politics of managing and orchestrating the adaptive challenge between the winner and losers, both in domestic and international settings, is not going to be an easy task.

Source: IPCC, MGI

Asia on the frontline

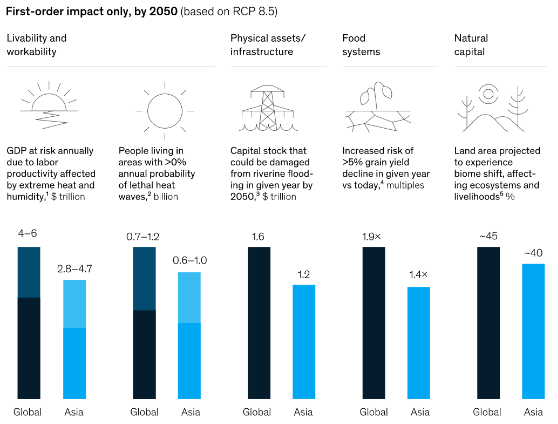

While the climate risks in food systems and natural capital in Asia are expected to increase at a relatively similar pace as the global average, in many ways, Asia stands out as being more exposed to physical climate risk than other parts of the world in the absence of adaptation and mitigation. Under the higher RCP (Representative Concentration Pathway) 8.5 CO2 concentrations, by 2050, between 600 million to one billion people in Asia will be living in areas with a nonzero annual probability of lethal heatwaves, while the global total is expected to be between 700 million to 1.2 billion – meaning that a substantial majority of these people will be in Asia. The Asian GDP at risk is expected to account for more than two-thirds of the total annual global GDP impact, and about $1.2 trillion in capital stock in Asia, equivalent to about 75 percent of the global impact, is expected to be damaged by riverine flooding by 2050. As the figure below shows, people, physical assets, and GDP impacted by rising heat and humidity may be more at risk in Asia than globally.

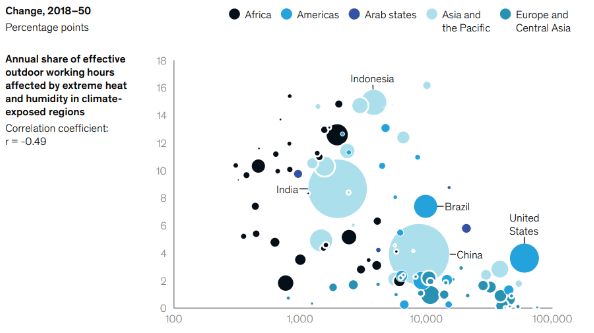

With a varying degree of climate profile, exposure, and response to climate risks, different groups of Asian countries could see different types of extreme cases. Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan could face much higher probabilities of lethal heat waves, extreme precipitation events more frequent than in the second half of the 20th century, with climate change having the biggest negative impact on their crop yield. Emerging countries such as the major Southeast Asian countries (Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam) are also projected to see extreme increases in heat and humidity, which the impact on workability will be significant as the economies have a high percentage of outdoor and labor-intensive sectors.

Countries like Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea, on the other hand, are expected to be an agricultural net beneficiary of climate change in the near term, although drought, typhoon, and extreme precipitation risks are likely to increase in some part of these countries which are also likely to see biome shift and the change of climate classification. China, in an aggregated sense, is predicted to become hotter. The country is also expected to be an agricultural net beneficiary of climate change in the near term; however, risks in infrastructure and supply chains will increase due to more frequent extreme precipitation events and typhoons – this is a particularly important point to note, given the country’s role in regional and global supply chains.

Just as in the global analysis, countries with lower levels of per capita GDP are most at risk from the impacts of climate change. Those economies are subject to climates closer to physical thresholds that affect human being’s ability to work outdoors as they rely more on outdoor work or natural capital. They have less financial means to adapt as well.

Challenges are mounting in the region; however, there seems to be fairly reasonable evidence to remain optimistic that Asia is positioned to address the risks and capture the opportunities. Infrastructure and urban areas are still being built out in many parts of Asia, which gives the region a chance to ensure that what goes up is more resilient and better able to withstand heightened risk. At the same time, key economies in the region are leading the world in technologies, from electric vehicles to renewable energy, that are necessary to adapt to and mitigate climate change.

How capital markets and banking can move the needle forward

Until more recent years, the energy and automotive sectors were ahead in terms of thinking about climate risks. That has changed dramatically over the past one or two years; the banking sector is taking the lead in the capital markets now, initially driven by regulation coming out of Europe with a recognition that climate change can present an existential threat to the financial system. The private equity capital is taking a stance around opportunity into the new green economy, and we see such interest starting to be reflected in valuations.

A greater understanding of climate risk could make financial markets bring forward risk recognition, especially in affected regions, with consequences for capital allocation and insurance – make long-duration borrowing unavailable, impact insurance cost and availability and reduce terminal values. While policymakers and businesses will need to respond, financial institutions that directly handle risks can potentially play a significant role. Much as the consideration about information and cyber-risks have become integrated into corporate decision making, climate considerations will also need to be featured as a major factor in decisions, given its short and long-term consequences. The right tools, analytics, processes, and governance need to be put to properly assess climate risk and find ways to decarbonize to reduce the further buildup of risk as well.

Banking

As intermediaries and providers of capital, banks play a crucial role in socio-economic development that includes managing the physical and transition risks of climate change. While the regulatory pressure is driving banks at the moment – some have already made a start, and many are formulating strategies, building capabilities, and creating risk-management frameworks – there is also a commercial imperative in financing the green. While this will require specialized skills to protect balance sheets and manage the risk, oftentimes, banks lack the technical skills required to manage climate risk and the quants required to build counterparty or portfolio level models in certain locations or industry sectors. While focusing on enablers, banks will need to budget for increased inputs of resources in data, technology, talent, etc., as they make pragmatic, adequate, and comprehensive preparation to reach for risk maturity. Hasty actions can only increase the risk of missteps.

Corporations will increasingly become more vulnerable to value erosions due to climate risks that could undermine their credit status, such as the risks from coastal real-estate losses, land redundancy and forced adaptation of sites, etc. These, in turn, can have negative consequences on banks due to increases in stranded assets, uncertain residual values, potential harm in market reputation if banks are not perceived to support their customers effectively enough. In a new competitive environment in which banks are often judged on their green credentials, e.g., rating agencies such as S&P’s are also incorporating climate factors into their assessments, it makes sense for the banks to develop sustainable-finance offerings and to incorporate climate factors into capital allocations, loan approvals, portfolio monitoring, and reporting. Not simply because of the market pressure, but the climate-risk timelines closely align with bank risk profiles. With the material risks on a ten(or longer)-year horizon, which is not far beyond the average maturity of loans, banks are forced to write off stranded assets. Some banks have already made a move, ramping up sustainable finance, including discounts for green lending, and mobilizing new capital for environmental initiatives.

Insurance

It is estimated that only around 50 percent of losses today are insured, a condition known as underinsurance, which may grow even worse as extreme events unfold more frequently. While insurance cannot eliminate risk from a changing climate, it is a crucial shock absorber to help manage the risks. Thus, underinsurance reduces resilience. Appropriate insurance can also encourage behavioral changes by sending the right risk signals.

Instruments such as parametrized insurance and catastrophe bonds could provide protection against climate events, minimizing financial damage and allowing speedy recovery after disasters. These products may help; however, climate change means that many of the technical insurance capabilities will need to evolve. Some insurers have started moving into the direction, for instance, working with customers to increase resilience of their infrastructures, facilities, and supply chains, but more can be done. The traditional models or past loss experience will not be predictive of the future. Underwriting space will have to come up with new solutions based on new portfolio management techniques that can embrace emerging hazards.

Insurance will also need to overcome a duration mismatch, e.g., asset owners or physical supply chains in place may expect long-term stability for their insurance premiums, whereas insurers may look to reprice annually in the event of growing climate hazards.

Given the global spatial nature of climate risk, mobilizing finance to fund adaptation initiatives, particularly in developing countries, is also crucial. This will require public-private partnerships by multilateral institutions to prevent capital flight once climate risks are recognized in such countries. While innovative products and ventures have been developed to broaden the reach and effectiveness of these measures, governments of developing countries are increasingly looking to insurance and reinsurance carriers, as well as other capital markets, to improve their resiliency to climate impacts and to give assurances to the institutions and investors considering putting money in the particular region.

source: McKinsey Global Institute

Concluding remark: towards decarbonization investments

Climate science shows that the risk from further global warming can only be stopped by zero net greenhouse gas emissions, meaning that decarbonization investments, in particular the transition to renewable energy, need to be considered in parallel with adaptation measures discussed above. Prudent risk management would suggest limiting future cumulative emissions to minimize the risk of activating negative feedback loops.

There will be an ever-increasing drive and push toward transparency and disclosure. Some of the regulators are already asking for disclosure of physical and transition risks. At a macro level, the risk is increasing day by day, meaning that simply transferring those risks will not solve the problem. Insurers are particularly familiar with natural events and physical risks, but transition risks may be a blind area. Building capabilities in understanding the implications of transition risks – about how to transition the high-carbon economy in an orderly manner to a greener or green one – may open up new opportunities. Now is the time that stakeholders consider assessing their decarbonization potential and opportunities arising from it.

About the author

Ji-in (Magdalena) Seol is

a Visiting Fellow at SNU AC. She has extensive experience in multilateral institutions, having worked with various DFIs and IOs, where she collaborated in major policy-makings such as the G20 Inclusive Business Framework and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Most recently, she led a major renewable energy initiative in Africa at the African Development Bank, and prior to this, she served as an Assistant Secretary to the President for Climate and Environment in the Office of the President of South Korea, managing key globalization agenda related to climate change and national competitiveness. She was in the Geopolitics of Renewable Energy Project and the Environment and Natural Resources Program at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs and the Government Innovation Program at Harvard’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation.

This analysis has been prepared with the grant support of the Visiting Scholar Fellowship at Seoul National University Asia Center.

1) Bank of England, Climate change: What are the risks to financial stability? https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/knowledgebank/climate-change-what-are-the-risks-to-financial-stability (accessed on Feb. 3, 2021)

References

- Buchner, et al., Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2019, Climate Policy Initiative, November 2019

- Eceiza J., et al., Banking imperatives for managing climate risk, McKinsey&Company, May 2020

- Global Green Growth Institute, Mind the Gap: Bridging the Climate Financing Gap with Innovative Financial Mechanisms, Insight Brief 1, November 2016

- McKinsey Global Institute, Climate math: What a 1.5-degree pathway would take, April 30, 2020

- Stavins, R., “From the Science to the economics and politics of climate change: An introduction,” Chapter 1 in Our World and Us: How Our Environment and Our Societies Will Change, ed. Katinka Barysch, Allianz SE, 2015.