Jörg Michael Dostal (Associate Professor, Graduate School of Public Administration, Seoul National University)

From today’s point of view, Korea’s national division has lasted for more than six decades. Many people have long stopped thinking about alternatives. Yet the Korean status quo currently appears to be challenged due to the dynamism of inter-Korean politics and larger geopolitical transformation in Asia. Geopolitics concerns the study of the influence of geographical factors on human history and policymaking. This type of political analysis should always be based on a ‘cybernetic’ way of reasoning, namely the changes in the behavior of one state actor influencing all others. It is difficult to consider the rise of China, the nuclear ambitions of North Korea (the DPRK), U.S. foreign policy, or the relationship between the three great powers (China, Russia and the U.S.) in isolation from each other. In the global context, the two Koreas or the unified Germany are at best middle powers. Their geopolitical autonomy is limited because they must always take the greater powers and their interests into consideration when thinking about policy choices.

Two Divided Countries, One Unification

Looking at the history of the divided Korea and the formerly divided Germany (two states, the Federal Republic of Germany, or West Germany, and the German Democratic Republic, or East Germany, existed between 1949 and 1990, and these two states were physically divided by a wall between 1961 and 1989), their division was the result of global geopolitical conflict. In the early Cold War context, the two Korean and two German states were made to accept the geopolitical patronage of larger external powers. This patronage was not for free. By obtaining economic and military assistance from their big brothers, the divided countries also had to offer their national territories as a potential (and, in the Korean case, actual) battle space. From the point of view of their geopolitical patrons (the U.S., Soviet Union, and also China in the Korean case), the divided countries were buffer states and their sovereignty was permanently suspended.

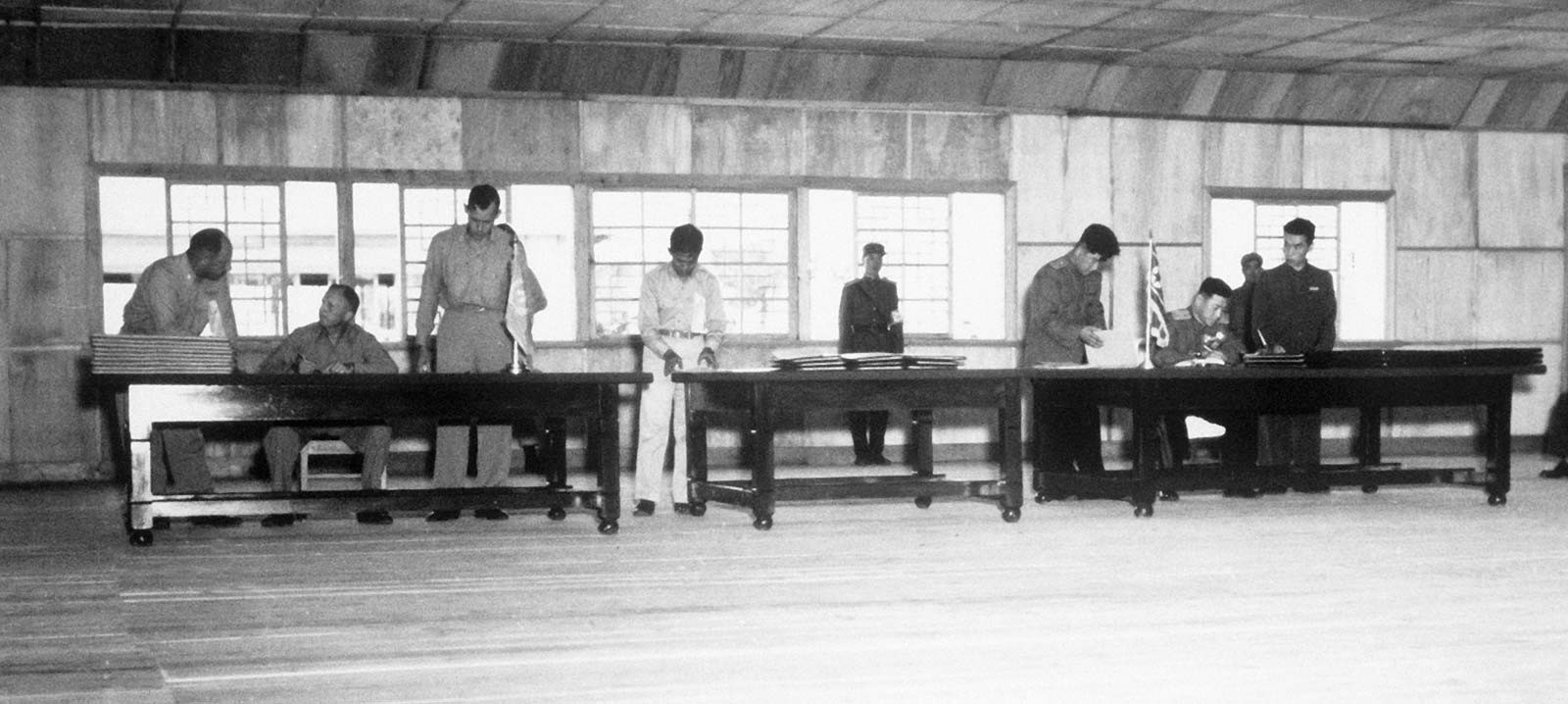

Source: Picture by U.S. Navy, F. Kazukaitis, U.S. Department of Defense

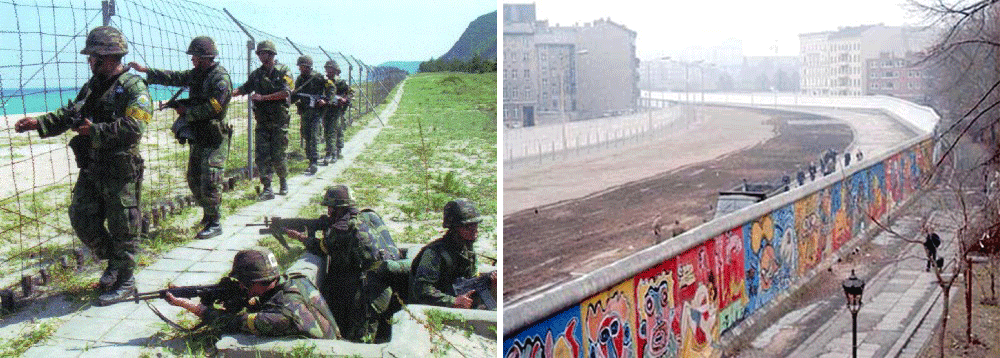

Geopolitical similarity aside, the Korean and German cases differ in other respects. Korea’s national division has been much more severely enforced. While the wall between the two Germanies was mostly open in one direction (West Germans were for most of the period of national division between 1961 and 1989 able to visit East Germany, and East German pensioners were normally allowed to visit West Germany), this has not been the case in Korea. During the German division, most East Germans could watch West German TV while citizens of the DPRK do not have any direct and legal access to South Korean media.

Nevertheless, the severity of Korea’s division has not changed the fact that both Korean states belong to a single nation based on shared language and – at least historically – shared culture. Thus, there exists a ‘Korean national question’ that demands some political answer. Since the end of the Korean War in 1953, the status-quo has been the fallback option, although changes in the geopolitical environment of the two Koreas might question its future viability. Moving to a closer form of political and economic cooperation such as confederation or, perhaps, reuniting at some future point would also be conceivable. Theoretically, an expedited national unification of the two Koreas as part of some large geopolitical agreement could be considered, although in reality it would be very difficult.

Source: Picture by French street artist Thierry Noir (1986) taken at the Bethaniendamm in Berlin-Kreuzberg

After all, German unification ultimately came about as a surprise – due to the willingness of the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, to accept Soviet withdrawal from Eastern European countries that had fallen to the Red Army during the final phase of the Second World War as part of the Soviet Union’s defeat of Nazi Germany. Nobody seriously expected such voluntary withdrawal from the Soviet Union, least of all West German politicians or academic experts in the field of international relations!

German and Korean Experiences Compared

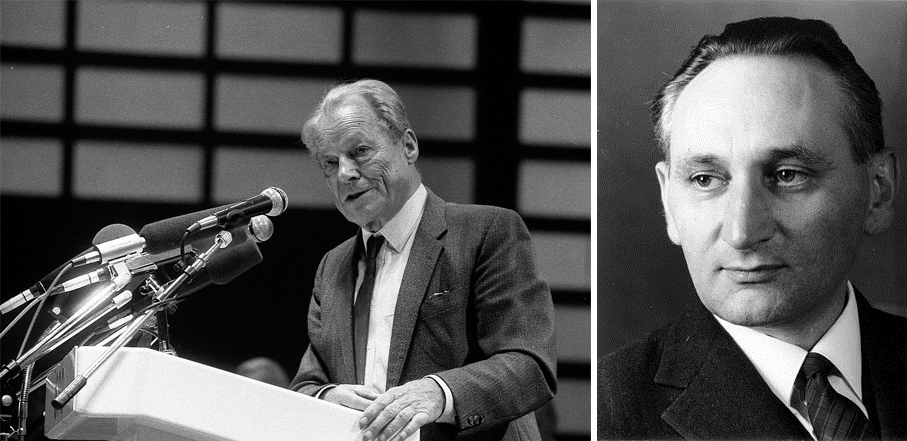

The objective of this short article is to extract some relevant lessons from the German experience pre-unification for the two Korea’s current situation. This concerns in particular what has been referred to in German debates between the early 1960s and 1990 as ‘New Eastern Policy’, based on the political efforts of Wily Brandt, the first Social Democratic Chancellor of West Germany from 1969 to 1974, and his main strategic advisor Egon Bahr. Before explaining what is still – or perhaps once again – relevant about the German case in the Korean context, the next section very briefly outlines some geopolitical theory relevant to understand the situation of the divided Korea. It then explains the German ‘New Eastern Policy’ and how some of its contents might be applicable in the current Korean context.

Geopolitical Ideas in the Asian Context

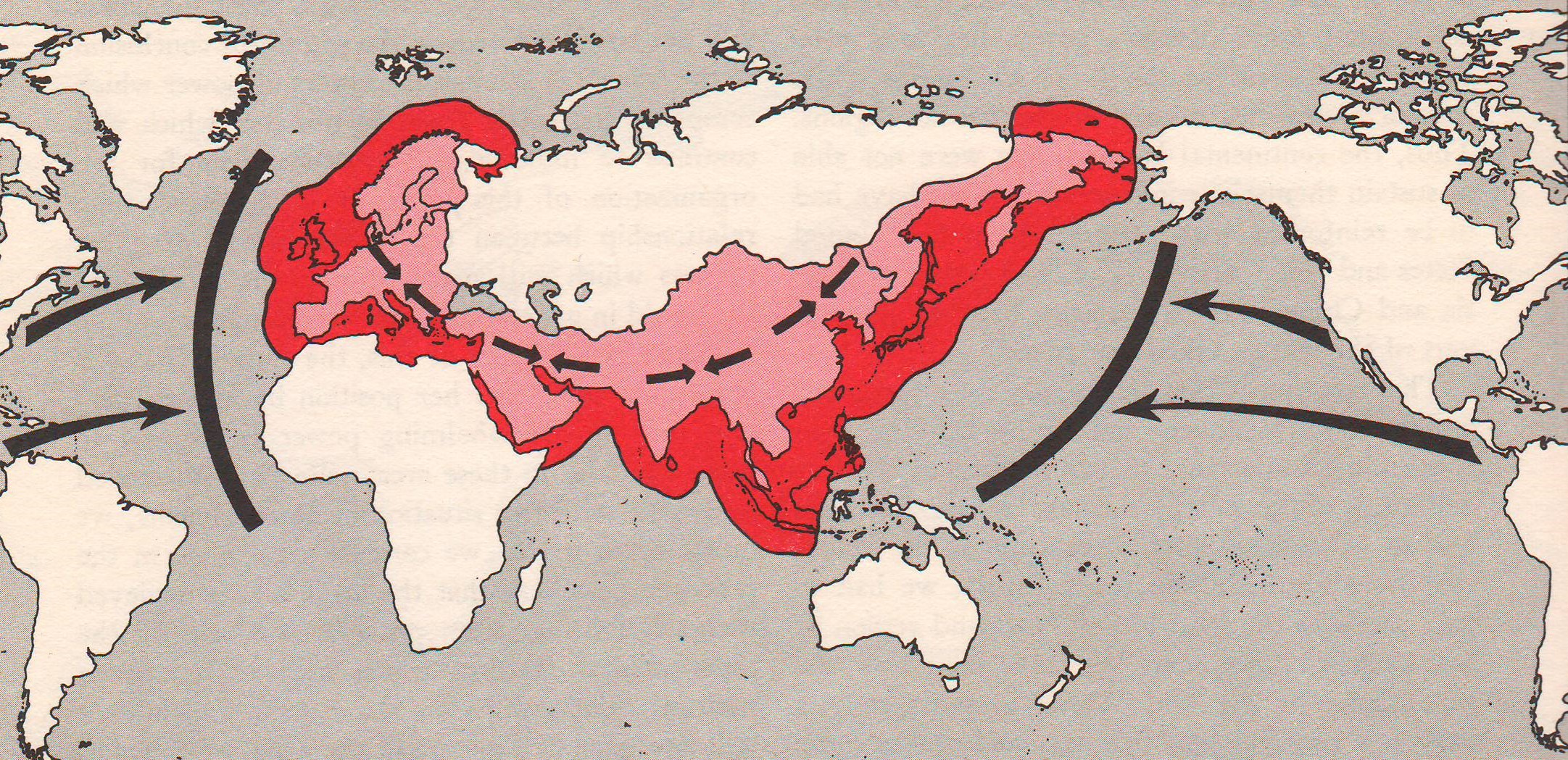

Modern geopolitical thinkers have notoriously disagreed about the relationship between geographical factors and political and economic power. An American scholar in classical international relations theory suggested that control of global trade routes, strategic harbors, and maritime choke points would deliver superiority to naval powers over land powers (Mahan, 1900). Meanwhile, a British author suggested the contrary, namely that land powers could successfully resist naval powers. He located what he termed the geopolitical ‘pivot’ or ‘heartland’ of world politics in the center of the Asian continent at some point in Siberia, which he considered as a natural fortress totally inaccessible to sea powers (Mackinder, 1904). He further expected the development of land-based transportation such as railroads as a way for land powers to better coordinate their efficiency as states and to further develop their economic and political power vis-à-vis the sea powers.

A German geopolitical thinker argued before and after World War 1 that land powers should resist the dominant naval powers of his time – Britain and the U.S. (Haushofer, 1926). He advocated for the geopolitical alliance of Germany, the Soviet Union and possibly China to form an ‘East Eurasian Continental Bloc’ in order to exclude the western sea powers from access to Asia. This was rhetorically presented as assisting in efforts to advance the continent’s liberation from colonialism.

In fact, authors such as Mahan, Mackinder and Haushofer, despite their political differences, all aspired to explain conflicts between the great powers over supremacy in Asia. The main contenders in this conflict until 1945, namely the U.S. and Japan as well as Britain and Germany, had all made efforts to become hegemons in the Asia-Pacific region. The main loser had been China, which suffered from the external meddling of the outside powers based on foreign sponsorship of Chinese warlords fighting each other, especially since the collapse of the central government authority in the mid-1920s and until 1949.

During World War 2, Nicholas Spykman, a strategic thinker at Yale University, developed what is in some respect still the present day U.S.-American geopolitical doctrine of global hegemony. He thought that the US as a major combined land and sea power was set to overcome the limitations of earlier imperial powers – by constructing a global system of military bases and, as a consequence, was set to emerge as the dominant political player in each region of the world (Spykman, 1944). He further suggested that geopolitical power was neither primarily naval- nor land-based but located in what he termed ‘rimlands’, namely coastal areas of the world in which most of the population and economic activity is concentrated.

Source: Spykman, Nicholas J. The Geography of the Peace.Edited by Helen R. Nicoll. Yale, NJ: Yale University Press, 1944.

However, the Chinese Revolution of 1949 unexpectedly forced the U.S.-backed Chinese political actors to flee from the mainland to Taiwan. This raised the question of how to construct a new U.S.-led front against communism. The political combination of China and Russia, apart from representing ‘communism,’ also geopolitically stood for the alliance between the two major land powers in Eurasia. As a result, the significance of Korea as part of the rimland zone grew in U.S. strategic thinking.

Korea and Geopolitics

During the Korean War from 1950 to 1953, inter-Korean clashes quickly turned into a global conflict. The U.S.-led military intervention combined naval and air power with ground troops using superior technology and strategic bombing. After its counter-intervention, Mao’s China relied on the more traditional advantage of close proximity to the physical battleground and larger number of ground troops. In turn, the Soviet Union intervened in a limited manner by inserting its then cutting-edge MiG 15 jet fighters into the top left-hand corner of North Korean airspace, hinting that it would be able to match the U.S. in terms of military technology. The Soviet Union also provided weapons to the North Koreans. This all showed that the U.S. could only ‘win’ the Korean War by also attacking China (the source of many troops) and the Soviet Union (the source of many weapons). This would have meant nuclear war. Fortunately, the checks and balances of the U.S. political system allowed ending the Korean War before it escalated regionally or globally.

The events confirmed that the two Koreas act as buffer states of the great powers. Ever since 1953, South Korea has remained the only continental bridge head of the U.S. in East Asia. In turn, North Korea’s existence was useful from the point of view of China and the Soviet Union. From today’s point of view, it is therefore important to understand how classical geopolitical ideas continue to influence the behavior of the major relevant powers in the region, namely China, Russia, the US, Japan and, much less significantly, some European and Asian middle powers.

China’s geopolitical doctrine of ‘peaceful rise’ and its geopolitical project of the ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI) are informed by classical geopolitical thought briefly sketched above. In particular, China aspires to match the US in becoming a major naval and land power at the same time. Subject to maintaining its domestic stability, China will likely expand its influence in Eurasia and globally. The US will in turn undertake efforts to contain China. All three powers – including Russia – also compete in terms of political, military, and economic institutions. In particular, Russia and China have invested significant political capital founding the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, headquartered in Beijing, to function as a multilateral Asian security body without the inclusion of the U.S.

South Korea’s position as a middle power in Asia means that the preferences of the larger powers – China as main economic partner, the U.S. as security provider, and Russia as a potential major source of energy resources – all need to be considered in future decision-making.

West German ‘New Eastern Policy’: Willy Brandt and Egon Bahr

Since the founding of West Germany in 1949, its conservative leaders had rejected any serious negotiations with the East Germans. Instead, they insisted that West Germany was the sole legitimate German actor in international affairs. East Germany was expected to collapse at some future point. These views were dominant during the 1950s and early 1960s.

The social democratic party leader Willy Brandt and his advisor on inter-German affairs Egon Bahr started to challenge these views in the early 1960s. According to Brandt, a new West German policy toward the east (the Soviet Union and East Germany) required a new paradigm. He suggested turning toward a ‘policy of small steps’ and ‘confidence-building measures.’ In particular, Brandt argued that West Germany should ‘take care of its own affairs rather than to rely on others [namely the U.S.] to speak on our behalf’; should accept the territorial losses that Germany had suffered as a result of World War 2; should face the fact that a ‘permanent solution of the German Question could only emerge as the result of a lengthy process, and that both parts of Germany must find intermediate solutions for a rule-based peaceful coexistence’ (Brandt, 1976: 222, 240, 247).[1]

Another major principle of Brandt was rejecting the use of military force as a means of policymaking. Furthermore, he accepted that West Germany would first have to improve the relationship with the Soviet Union before improving the relationship with East Germany (the former was the patron of the latter). The goal of the new concept was ‘a policy of transformation. Real political and ideological walls need to be put down incrementally without conflict’ (Brandt, 1963: 14).

Along similar lines, Bahr argued in a 1963 speech titled ‘Wandel durch Annäherung’, which might be translated as ‘change by rapprochement’, that the ‘preconditions for reunification are only available with the Soviet Union’ and that German ‘unification is not a one-off action but a process with many steps and intermediary points.’ Bahr clarified that he did not advocate for uprisings in East Germany or a rapid collapse of the East German state since he expected this to result in bloody conflict and military counter action on the part of the Soviet Union. (The Soviet Union had earlier, in 1953, intervened militarily in East Germany to end an East German popular uprising.) He further suggested that the ‘dissatisfaction of our fellow countrymen [with their government] might be declining a little bit. But this is hoped for because it is another precondition in order to remove an element that could produce uncontrollable developments which must produce backlash.’ He also advocated for change by economic means – namely closer trade relations between the two Germanies – in order to incrementally improve the economic situation of East Germans (Bahr, 1963).

Source: https://www.willy-brandt-biography.com/politics/german-unity (on the left), The German Federal Archives/Bundesarchiv (on the right)

While Brandt and Bahr formed a team in terms of introducing the new policy – they both faced heavy criticism of West German conservatives accusing them of ‘betrayal’ of East Germans, a reaction that will not surprise South Koreans used to polemical exchanges between their own conservative and liberal camps – there was also an interesting difference between the two politicians in their basic approach to global politics. Brandt’s primary task was focusing on negotiations and charming the eastern side, particularly the Soviet leaders around Leonid Brezhnev, while Bahr’s mission concerned multilateral contacts with the other significant actors. Most importantly, Bahr established backdoor diplomacy with long-term U.S. National Security Advisor and subsequent U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, a German-born Jew who had left Nazi Germany as a refugee, had become a U.S. citizen, and had made his career in U.S. academic and foreign policy circles. Thus, Bahr added the realist and calculating approach to Brandt’s more idealistic profile.

In his political memoirs, Bahr stressed that his approach to international relations was strictly realist, namely he stated that ‘critics [of mine], especially in my own party [the West German Social Democrats (SPD)] have sometimes claimed that I would think too much in categories of states and power; well, wherever I was in the world I had to learn that partners were exactly thinking along these lines, independent from their passport and skin color’ (Bahr, 1995: 239). As part of his realist understanding of international relations, he was keen to establish direct working contacts with those who were tasked by national leaders to deal with international affairs. Building a close relationship with Kissinger was from Bahr’s point of view his national duty – independent from what he personally thought about U.S. foreign policy such as the then escalating US involvement in the Vietnam War. He certainly looked at U.S. foreign policy without illusions suggesting that ‘in the 1960s (…) Uncle Sam started to look more and more like the old great powers of Europe, with their tradition of national interest and utilitarianism covered up by pretty words. Only his power grew more and more increasing the distance to all others’ (ibid., 170). Summing up, the political team made up of Brandt and Bahr was powerful because they managed to address different target audiences, namely Brandt appealed to the general public in east and west while Bahr reassured U.S. elite politicians.

Implementing the ‘New Eastern Policy’ (1970-1973)

The new West German policy toward the eastern bloc countries was implemented after the 1969 West German national elections that brought a social democratic and liberal coalition government under Brandt’s leadership into office. Briefly afterwards, the newly elected Chancellor Brandt and his top assistant Bahr prepared the signing of a number of bilateral treaties between West Germany and four eastern countries, namely the Soviet Union (Moscow Treaty), Poland (Warsaw Treaty), East Germany (Grundlagenvertrag, or ‘Basic Treaty’) and Czechoslovakia (Prague Treaty).

Source: Picture from the Wikipedia (https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ostpolitik), translated German into English

Signed in 1970, the Moscow Treaty stated that West Germany accepted the territorial losses after World War 2 when formerly German territories had been taken over by Poland and the Soviet Union. The same Treaty indicated that the two sides would avoid threatening each other with the use of military force and would work toward a peaceful world order in line with Article 2(4) of the Charter of the United Nations stressing the principle of non-violence in international relations.[2] The Warsaw Treaty, signed in the same year, and the Prague Treaty, signed in 1973, also recognized the existing national borders. The inter-German Basic Treaty, signed in 1972, largely followed the text of the Moscow Treaty.[3] In this Treaty, the two German states mutually recognized each other at the level of ‘state law’. However, West Germany did not recognize East Germany as a foreign country under ‘international law’, since the demand to unify the two Germanies was written into the West German Constitution. By using the argument of constitutional legality, West Germany retained the original expectation that the two Germanies would unify at a later point, which was also reconfirmed by the West German Constitutional Court.

There were two immediate gains for West Germany from the new policy toward the east. First, West Germany quickly improved its trade relationship with the Soviet Union, and a deal on constructing a gas pipeline between the Soviet Union and West Germany helped to provide new access to non-Middle Eastern energy resources. Another major gain was that the two German states entered the United Nations in 1973 with two delegations, exchanged ambassadors, and increased their mutual economic cooperation.[4]

Security for Germany and Security from Germany

The signing of the four Treaties immediately improved the German and European security situation. From the point of view of Brandt and Bahr, the next two steps should have been the construction of a European peace order – based on mutual arms control followed by significant reductions in military spending and troop numbers on both sides – and, finally, efforts to proceed toward German unification. This process was expected to be based on the dual principle of ‘security for Germany’ and ‘security from Germany’, namely the recognition that unification of the two Germanies would only ever be possible if all the important external actors, especially the Soviet Union, would be willing to accept it (Bahr, 1995: 498-499).

In order to advance toward a European peace order, the new policies strongly focused on nuclear issues. According to Bahr, the most dangerous military threat for both Germanies derived from the so-called tactical or battlefield nuclear weapons stationed by the U.S. and the Soviet Union on the two German territories. These weapons – nuclear artillery and short and medium distance nuclear ballistic missiles – potentially allowed for a ‘limited’ nuclear war, that is to say the use of tactical nuclear weapons could have happened in a manner that destroyed the two Germanies without endangering the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Bahr believed that the complete removal of such weapons – also including chemical weapons stationed by the U.S. on West German territory – would improve the security situation for both Germanies.

Another dimension of the nuclear weapons problem was Bahr’s realization that the two super powers, the U.S. and the Soviet Union, jointly shared an interest in efforts to avoid further proliferation of nuclear weapons. Therefore, he suggested that non-nuclear weapons powers, including the two Germanies, should sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). He believed that this step would underline that West Germany did not aspire to regain the status of a great military power. Crucially, West German security interests would also be served in the sense that this step avoided the drafting of West German soldiers to fulfill junior roles in connection with the U.S. nuclear arsenal.

Finally, with regard to conventional military threats, Bahr suggested general troop reductions in line with the principle of ‘Mutually Balanced Force Reduction.’ He advocated for ‘a zone in central Europe around the two German states in which there exists no conventional military superiority any longer in order to make any surprise military attack impossible’ (Bahr, 1995: 500-501).

Summing up his political life experience after the reunification of the two Germanies, Bahr argued that the recognition of the status quo at the beginning of the 1970s had been a major step to ultimately overcome the division of Germany. He suggested that the confidence- building activities toward the Soviet Union had helped preparing the situation in 1989 and 1990 when the U.S. and the Soviet Union allowed German unification to proceed. At the same time, Bahr was disappointed about the failure to establish a permanent European peace order after German unification. From his point of view, the U.S. took advantage of the weakness of Yeltsin’s Russia in the 1990s to fill the geopolitical space in Eastern Europe vacated by the Soviet Union with U.S. influence, thereby excluding Russia from the post-Cold War European security architecture. Until his death in 2015, Bahr continued to stress the need for Germany to maintain friendly relations with Russia – in its own national interest (Bahr 2015a, 2015b; see also v. Plato, 2002: 413-414; Platzeck, 2017).

What Lessons for South Korea?

Turning now to South Korea’s current situation, one might discuss the German unification story along three guiding lines, namely (1) the larger regional picture; (2) the question of the great powers; and (3) the inter-Korean issues.

From the South Korean point of view, its larger regional strategy must be informed by realization that any kind of future advance, may it be unification, confederation, or simply better relations with the DPRK based on an inter-Korean security partnership, all depend on support from other states in Asia and beyond. In this context, confidence in the stability of South Korean democracy is in itself an important asset. In addition, South Korea should consider creating a new forum for regional peace and security, or should at least invest more resources into existing multilateral bodies to strengthen regional good will.

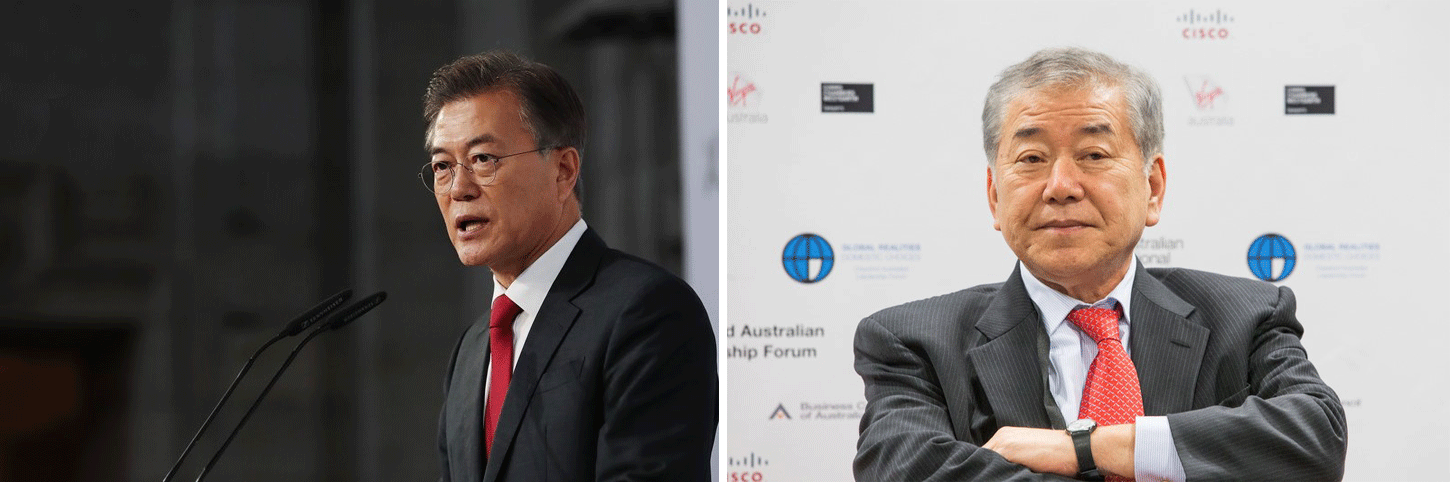

Source: The Blue House, http://english1.president.go.kr/PhotoVideo/Photos/37?page=40 (on the left), Craw Forum Flicker website, https://www.flickr.com/photos/crawfordforum/27775467581 (on the right)

The Moon Jae-in administration’s special efforts to build a close bilateral relationship with Vietnam, as another regional middle power, already point in the right direction. Moreover, South Korea should also invite other interested states and civil society organizations to participate in efforts to improve relations with North Korea and regional security in East Asia. After all, inter-Korean relations have an Asian and global dimension, and non-Koreans’ interests in the situation on the Korean peninsula could in fact constitute an important asset for South Korea.

As far as the great powers China, Russia and the U.S. are concerned, South Korea as a middle power does influence the calculus of decision makers in these countries only in a limited manner. Realistically speaking, South Korea’s major interest is to maintain good relations with all three powers (and also with Japan), since they can all contribute to improved relations between the two Koreas.

One crucial current issue from South Korea’s point of view is potential conflict between China, Russia and the U.S. concerning strategic security in Eurasia. During the Cold War, there was general agreement that nuclear strategic balance required global arms control, namely ‘offensive’ and ‘defensive’ missiles were supposed to be controlled numerically in order to avoid arms races. Post-Cold War, however, military spending is no longer balanced. According to the latest 2017 Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) figures on military spending, the US currently spends $611 billion, China spends $215 billion, and Russia’s comparatively more modest spending amounts to $69 billion. By comparison, South Korea spends $39 billion, while a South Korean dollar estimate of North Korean spending in 2015 suggested a figure of $7 billion.[5] In 2002, the U.S. withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missiles (ABM) Treaty. This was followed more recently by the stationing of ‘defensive’ U.S. missiles in Poland, Romania and South Korea, which questions nuclear strategic balance and could trigger a new arms race. This is particularly problematic from the point of view of China, which has a much smaller nuclear arsenal in comparison to the two other great powers.

In the context of North Korea’s development of a nuclear arsenal, it appears at least theoretically possible that a ‘package deal’ of withdrawing the North Korean nuclear program in combination with the withdrawal of U.S. ‘defensive’ missiles (the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense Program (THAAD)) from South Korea could meet the strategic requirements of China. In addition, this could be combined with efforts to create an arms control zone in both Koreas – balanced military reductions as part of a future security partnership between the two Koreas. The guiding question from the South Korean point of view should always be what the three great powers could gain or lose politically from changes in the regional status quo. South Korea should be ready for geopolitical windows of opportunity.

Finally, the inter-Korean relationship is from the Korean point of view the most crucial one since it is the only strategic relationship that Korean policymakers can independently control. In order to peacefully improve on the status quo, all kinds of small steps need to be combined. The most obvious one is economic collaboration, agreement on military de-escalation, and people-to-people diplomacy. Contrary to earlier rounds of improvements in the inter-Korean relationship – such as the ‘sunshine policy’ of earlier liberal administrations – these steps should be quickly institutionalized. The current South Korean liberal administration must also try including South Korean conservatives in efforts to improve the relationship with the North. The goal should be achieving a higher degree of southern political consensus, which will take much time and effort. Brandt and Bahr were also initially strongly criticized by German conservatives before their policies became more broadly endorsed.

Is it Going to Work?

None of what has been discussed in this paper can answer the question whether North Korea is going to engage in denuclearization, of course. One might argue, as President Moon Jae-in has frequently done, that ‘[t]he [South Korean] government is (…) carefully managing the situation on the Korean peninsula because establishing peace on the peninsula goes together with complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula’ (Jeong and Kim, 2018, emphasis added). Yet the same article also notes that ‘[d]enuclearization talks between the North and the United States are deadlocked.’

One therefore must ask the inconvenient question whether improvements of the inter-Korean relationship should still proceed even if there were to be no, or no immediate, progress on the nuclear file. To be sure, pessimists have argued that the DPRK is not going to denuke. U.S. academics such as John Mearsheimer have suggested that it would be irrational for the North to do so (Yonhap News, 2018). The most recent decision of the U.S. administration to cancel the Iran nuclear deal – against the explicit wishes of other contracting parties such as the European Union countries – does little to make agreements with the U.S. appear to become more attractive from the Northern point of view.

In some respect, the current situation is not fundamentally different from what it used to be under previous South Korean presidencies. The debate still concerns the issue of sequencing, namely should there be a ‘one-shot deal’ denuclearization of the North ‘tied to appropriate compensation in a single package’ (the scenario that has always been preferred by the U.S.), or should there be a more pragmatic process (Moon, 2011: 4, 13) of what one could call with reference to the German case a ‘policy of small steps’?

From the point of view of the past German experience, a policy of inter-Korean rapprochement should be maintained under almost any circumstances. If there is no quick progress on the nuclear issue, this should be accepted as a temporary backlash. In the German case, the policy of rapprochement also seemed to fail in the early 1980s when a new nuclear arms races occurred in Europe. Back then, the relationship between the political leaders of the two Germanies once again deteriorated. Yet it was still better than before, and some degree of trust remained between both sides due to their previous engagements during the 1970s. This meant that the danger of a military conflict was much reduced. Neither the two Germanies back then nor the two Koreas today can determine the behavior of the great powers. But they can control their own willingness to collaborate in order to deescalate tensions and for their own mutual advantage.

About the Author

Jörg Michael Dostal

is an Associate Professor in the Graduate School of Public Administration, Seoul National University and a Senior Research Fellow in the Centre for Syrian Studies, University of St Andrews (UK). He belongs to the editorial boards of the Korean-German Journal of Social Sciences and the Korean Journal of Policy Studies. jmdostal@snu.ac.kr

[1] All English-language translations of German sources are by the author.

[2] Full text of the Moscow Treaty available here: http://www.documentarchiv.de/brd/1970/moskauer-vertrag.html

[3] Full text of the Basic Treaty available here: http://www.chronik-der-mauer.de/material/178847/vertrag-ueber-die-grundlagen-der-beziehungen-zwischen-der-bundesrepublik-deutschland-und-der-deutschen-demokratischen-republik-21-dezember-1972?n

[4] The diplomatic missions of the two Germanies were referred to as ‘permanent representations’ rather than Embassies in order to highlight that the West German Constitution did not recognize East Germany as a foreign country.

[5] For the latest SIPRI figures on military spending, see: https://www.sipri.org/media/press-release/2017/world-military-spending-increases-usa-and-europe. For 2015 North Korean spending in dollar terms, see E. Shin, ‘North Korea underestimated defence spending, analyst says’, UPI World News, March 31, 2016, available at: https://www.upi.com/Top_News/World-News/2016/03/31/North-Korea-underreporting-defense-spending-analyst-says/2811459437466/

References

- Bahr, Egon. Wandel durch Annäherung, Tutzing speech, July 1963, available at: https://web.ev-akademie-tutzing.de/cms/fileadmin/content/Die%20Akademie/Geschichte/Wandel/Wandeldurchannaeherung.pdf

- Bahr, Egon. Zu meiner Zeit. München: Karl Blessing Verlag, 1995.

- Bahr, Egon. Kooperative Existenz. Für eine Verantwortungspartnerschaft mit Moskau und Washington, Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik, May 2015a, available at: https://www.blaetter.de/archiv/jahrgaenge/2015/mai/kooperative-existenz

- Bahr, Egon. Stabilität nur gemeinsam mit Moskau: Egon Bahrs letzte Rede, Bild, 20. August 2015b, available at: https://www.bild.de/politik/inland/egon-bahr/letzte-rede-42260152.bild.html

- Brandt, Willy. Denk ich an Deutschland…, Tutzing speech, July 1963, available at: https://www.willy-brandt-biografie.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Rede_Tutzing_1963.pdf

- Brandt, Willy. Begegnungen und Einsichten. Die Jahre 1960-1975. Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe, 1976.

- Haushofer, Karl. Der Ost-Eurasiatische Zukunftsblock. Zeitschrift für Geopolitik, Vol. 2, No. 2, 1925: 81-87.

- Jeong, Yong-soo, Kim, Sarah. Envoy’s goal: Meeting with Kim, Korea Joongang Daily, 4 September 2018.

- Mackinder, Halford J. The Geographical Pivot of History. Geographic Journal, Vol. 23, No. 4, 1904: 421-437.

- Mahan, Alfred T. The Problem of Asia and Its Effect upon International Politics. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1900.

- Moon, Chung-in, Between Principle and Pragmatism: What Went Wrong with the Lee Myung-bak Government’s North Korean Policy?, Journal of International and Area Studies, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2011: 1-22.

- Plato, Alexander v. Die Vereinigung Deutschlands. Ein weltpolitisches Machtspiel: Bush, Kohl, Gorbatschow und die geheimen Moskauer Protokolle. Berlin: Christoph Links, 2002.

- Platzeck, Matthias. Europäische Friedensordnung und das Verhältnis zu Russland, 12 June 2017, available at: http://www.deutsch-russisches-forum.de/egon-bahr-symposium-2017-mit-matthias-platzeck-europaeische-friedensordnung-und-das-verhaeltnis-zu-russland/8419

- Spykman, Nicholas J. The Geography of the Peace. Edited by Helen R. Nicoll. Yale, NJ: Yale University Press, 1944.

- Yonhap News. N. Korea will not give up nuclear weapons: Mearsheimer, 20 March, available at: http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/news/2018/03/20/0200000000AEN20180320010200315.html