Peter G. Moody (SNUAC)

In my effort to document a political and cultural history of North Korean music, I recently came across a 1956 book published by the (North) Korean Composers’ Alliance Central Committee (조선작곡가동맹중앙위원회) called Korean Music after Liberation or alternatively Post-Liberation Korean Music

(해방후 조선음악, 1956). As an edited volume covering various topics ranging from the State Music School in Pyongyang, the Soviet influence on North Korean music, children’s music initiatives, and local music activity, the work aimed to provide a comprehensive even if sanitized account of music development in the northern half of the Korean peninsula from 1945 up until then.

When reading through the first several pages of the text, I became aware of the tension that existed between the burgeoning of diverse works of music heralding Korea’s newly liberated status and the reluctance to embrace certain genres of music deemed harmful or disruptive to society in some way, such as American jazz. From all indications, the affix hu (후) attached to the word liberation in the book’s title merely denoted “after” or “post” in a temporal sense. Nevertheless, the resulting term haebanghu, which I have translated here as “post-liberation” compelled me to reflect upon just how

liberated the conditions actually were for individual musicians throughout the decade the book

chronicled, in the North as well as the South. Thinking back about the lives of North Korean musicians I was researching, I wondered if the term “post-liberation” itself could serve as a useful analytical lens to illustrate the increasing constraints writers and artists were up against as the ideological and social tensions on the Korean peninsula intensified.

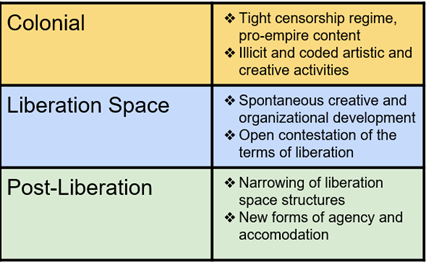

By utilizing the notion of post-liberation to detail what life was like for certain musicians, I do not

intend to overshadow the already existing concept of “liberation space.” Emerging in South Korea in the 1980s, the liberation space lens has been a much-needed corrective to state-centric accounts

as it has drawn significant attention to the voices and perspectives of those who did not fit neatly into the Cold War binary (See for instance Hughes, 2012; Zur 2017).

As a temporal category for the entire 1945–1950 period, however, the term liberation space could

be problematic. At the very least, it could misrepresent the fact that for many artists, especially musicians, the spaces for creative autonomy on both sides of the 38th parallel severely narrowed over time. A portrayal of “post-liberation” then could act as a critical supplement to help distinguish

between the instances of spontaneous artistic activity and expression that did take place (i.e., libeation space) and when artists and writers had to turn to new forms of agency as well as accommodation in order to continue creating (i.e., post-liberation).

If we were to treat liberation space and post-liberation as phases following Japanese colonialism

If we were to treat liberation space and post-liberation as phases following Japanese colonialism

and accompanying the drift towards national division, when would liberation space stage end and

post-liberation begin? This is another instance in which a general periodization scheme can only

fail us. Did liberation space give way to post-liberation during the violent crackdown to the Sinuiju

protest in the North on November 23, 1945 or when the US military government in Korea decided to end the spontaneously-formed people’s committees in the South on December 12, 1945?

Did the 1947 ban on leftist political and artistic organizations in the South mark a state of post-liberation, or was it the intense and ongoing social pressure to comply with the directives of the Korean Workers’ Party in the North that created the conditions for such a predicament?

Since the circumstances differed from individual to individual, there is clearly no single event or decision that universially constrained political and artistic activties. As a way of illustrating the multiplicity of factors weighing on divergent post-liberation trajectories, I provide accounts of two musicians

below: Kim Sun-nam (1917–1983) and An Ki-yong (1900–1980). Both migrated from the South to

the North, and as high-profile cultural figures, they faced precarious prospects in both Koreas.

Kim Sun-nam (김순남): A Controversial Musician in the North and South

Kim Sun-nam was an modernist composer and pianist who faced backlash for his works of music

and political leanings in the South as well as the North. He was born in Seoul in 1917 and exhibited musical talent at a very young age. In 1938, he ventured abroad to about the only place he could gain music expertise at the time, Japan.

Ironically, it was in Japan where his Korean nationalist and leftist political orientation really blossomed. He grew interested in the proletarian movement from one of his Japanese teachers, but once the Pacific War began, he returned to Korea. In December 1944, he managed to hold a recital, which was the first according to many critics at the time to exhibit “modernist techniques and atonal elements.” It was also a national music concert because he included a medley of Korean folksongs (노동은, 2017).

Upon liberation, Kim became a leading cultural figure in organizations such as the Korean Music Construction headquarters and the left-leaning Korean Musicians’ Alliance. Within this liberation

space, he composed the march “Liberation Song” (해방의 노래). The lyrics were written by the

famous poet Im Hwa (1908–1953), and the two closely collaborated. In expressing frustration

about the slow pace of land reform in the South, the second verse of the song included the lines “[When it comes to] the land and factories that were taken./ Take them back with just hands!” Lyrics such as these risked tensions with the authorities.

“Song of Liberation” with lyrics.

Meanwhile Kim Sun-nam composed art songs, such as “Sanyuhwa” (산유화) or “Mountain Flower.”

This piece was a different sort of liberation music than his liberation marches because it departed from both the Western triad (three-note chord) convention as well as the yona nuki pentatonic scale

that dominated Japanese popular music (노동은, 1988).

A 1994 recording of “Sanyuhwa,” sung by the world-renowned soprano Sumi Jo.

Kim Sun-nam then became post-liberated in the August 1947 when the chief of police ordered his

arrest for composing “Song of the People’s Resistance” (인민 항쟁가), which was suspected to be a

provisional national anthem north of the 38th parallel (Ahn, 2012). He then went into hiding during a period when leftist artistic and political organizations were suppressed.

For some time, Kim had an unlikely ally, Eli Haimowitz who was the US military’s chief music advisor in Seoul at the time. Upon showing his work to Haimowitz, the US music advisor considered Kim a genius and became deeply critical of the decision to target him. Haimowitz even let the Kim Sun-nam

hide in his car and also arranged for him to study in the US, but Kim Sun-nam turned down the

offer and decided to cross into North Korea instead (Park, 2021).

Once in North Korea, Kim Sun-nam quickly attained prominent positions including serving as a

representative of the Supreme People’s Committee and working a Professor of Music Composition at the State Music School (currently the Kim Won-gyun Conservatory). In 1949, Kim traveled to

Moscow for an October Revolution memorial event, and while he was there, he was able to show his work to the Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich. Impressed by what Kim had showed him, Shostakovich introduced the piece to his colleague Aram Khachaturian, who subsequently requested that Kim Sun-nam study directly under him (진회숙, 2013).

In Kim Sun-nam’s mind, the opportunity to learn from such a renowned composer was a dream

come true, but unfortunately for Kim, his time studying in the Soviet Union was short-lived. In early

1953, mere months after he began working with Khachaturian, Kim was recalled to Pyongyang (노동은, 2017) and then severely criticized for supposedly prizing foreign music and neglecting his

Korean roots (Szalontai, 2005).

By the end of the 1950s, Kim Sun-nam was exiled to the remote port city of Sin’po. For Kim to

return to the music scene, he had to demonstrate that he had made a conversion and accepted the Korean Workers’ Party’s principles for artistic creation. In his attempt to do so, Kim wrote an essay claiming that he learned that songs for the masses had to be “emotional, easy, and fun… with genuine and simple emotions that are not showy, relate specifically to their lives, and affect them directly” (조선음악 66/04).

Kim’s approach of making peace with party doctrine appears to have worked. In the mid-1960s,

he rejoined the faculty of the central music institution in Pyongyang and could compose new works once again (Howard, 2020). Within a few years of returning, however, Kim reportedly became ill with pulmonary tuberculosis, and spent the last years of his life battling the illness. For whatever reason, he has been rarely if at all mentioned in North Korean texts after the 1960s.

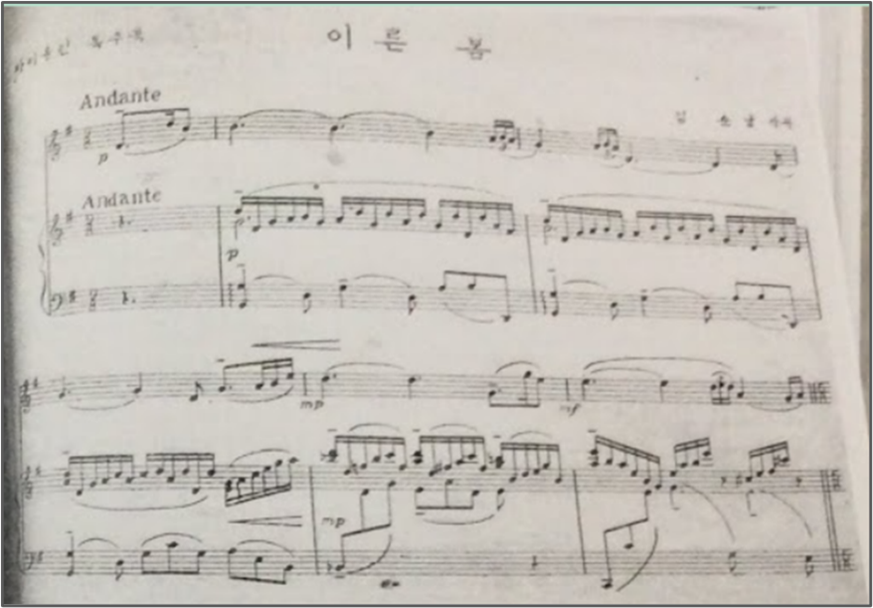

Five years after his 1983 death, Kim Sun-nam attracted attention in the South with the lifting

of the ban on the work of artists who migrated to the North. Kim’s daughter who remained in the South since her father’s defection, has conducted investigations to reconstruct his life (KBS, 1991), and this has included discovering sheet music for a violin and piano concerto called “Early Spring” (이른 봄) at the US Library of Congress (조선음악, 66/07). As a piece with a catchy and optimistic

melody as well as chromaticism and atonal diversions, it perhaps represents Kim seeking to balance the values of the society he lived in with his own creative standards.

Courtesy of the US Library of Congress

For a recent recording, listen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5uXnDKu1RQE

An Ki-yong (안기영): A Gifted Tenor and Longtime Music Educator

An Ki-yong was somewhat older than Kim Sun-nam but was just as active a music practitioner

during both the pre-liberation and post-liberation periods. He was born in the present-day South

Korean city of Kongju in 1900, but as a young man moved to China after the 1919 March First Movement to escape from Japanese authorities. In China, An met the famous independence activist Yo Un-hyung who recommended that he contribute to the independence movement by singing and

playing cornet for activist audiences (김득청, 2000).

An returned to Korea in 1923 with an objective in mind to dedicate himself to music. At a Methodist church in Seoul, he impressed a US missionary named Mary Young with his tenor voice. Young arranged for An to study at a music conservatory in Portland Oregon. Before An left, he sung the song “Leaving my Hometown,” composed by the famous Korean composer Hong Nan-pa (1897–1941), on a record.

Although An didn’t write the lyrics, he could almost certainly relate to them since he was leaving hometown for a distant land a second time:

I parted from my hometown and came to a strange land,

Sitting alone on a quiet night and thinking.

Oh, who can comfort my frustrated heart?

As I left my hometown, my mother

Held my hands in hers in front of our doorstep and wished me a safe journey.

Her words, ah, how they echo in my ears.

1925 recording of “Leaving My Hometown,” sung by An Ki-yong.

The melody of the song is the same as a famous North Korean song called “Sahyangga” (사향가) or “Nostalgia,” and the lyrics of the first verse of “Sahyangga” are nearly identical to the second verse of the earlier song. In the North, the authorship of “Sahyangga” is credited to Kim Il-sung (배인교, 2012). While the North Korean leader clearly did not compose the music, it is possible that he wrote the lyrics of the other verses since they refer to his personal experiences leaving Korea for Manchuria.

A contemporary North Korean music video of “Sahyangga.”

Once An returned to Seoul in 1928, he started teaching voice at Ewha University and then started composing music. One of his first songs was “Longing for the South of the River” (그리운 강남), and it was released on record the next decade with three of the most famous Korean vocalists at the time singing it.

A 1934 recording of “Longing for the South of the River,” sung by Kim Yong-hwan, Yun Kŏn-hyŏng, and Wang Su-bok

In addition to writing his own music, An was one of the first to adapt Korean folksongs to Western music notation. In 1930, he arranged for a female student chorus to sing them on a performance tour throughout the peninsula. At the time, An received a sharply negative response from some in the audience, mainly because there were those who associated folksongs with kisaeng or courtesan entertainment (오희숙, 2004). An was undeterred by the criticism and responded to it in article

published in the journal Eastern Light (동광) by stating, “Even if Korean folksongs have gotten

dirty, they are our songs and we must make them better” (31/05). To further elucidate his position, he compared Korean minyo or folksongs to “pearls buried in the mud” (Ahn, 2005).

Following liberation, An Ki-yong had experiences that were very similar to Kim Sun-nam’s. He

became the head of the vocal music division of the Korean Music Construction headquarters and

the vice-chair of the Korean Musicians’ Alliance. He also composed his own liberation song

called “Song of the Liberation Warriors,” which like Kim Sun-nam’s compositions from the same

period, had lyrics penned by Im Hwa.

Although not as politically active as Kim Sun-nam, An Ki-yong began to tread in the water of

political activity when he wrote the funeral dirge for his former mentor Yo Un-hyung following

his assassination by a right-wing terrorist.

An reached a state of post-liberation around the time he signed an April 1948 statement along

with over 100 cultural figures rejecting Korea’s imminent division with the upcoming elections that would only be held in the South (오희숙, 2004). He was eventually placed in a rehabilitation

organization to purge himself of his leftist political orientation (Ahn, 159–160).

There are conflicting accounts about how An ended up the North. It could have been voluntarily, or it could have been forced. But we do know that it happened during the first few months of the Korean War after the DPRK People’s Army had taken control of Seoul.

Once in the North, An Ki-yong followed Kim Sun-nam’s path of rising to the top of music-related

institutions very quickly. But unlike Kim, An aligned his interests more closely with the priorities of the Korean Workers’ Party. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, An became a regular contributor to the DPRK journal Choson umak or Korean Music.

Selected articles of An Ki-yong in the DPRK journal Korean Music (조선음악)

Sept. 1957 “Considering the Vocal Ranges of Our Songs from the Perspective of a Vocalist”

June–Aug. 1957 “To Heads of Circles Learning Vocal Music”

Sept. 1958 “A Happy Life”

Oct. 1958 “On Voice Change in Vocal Music”

Feb. 1960 “A Happy Life under the Sovereignty of the Republic”

Mar. 1965 “The Children’s ‘Doe’ and the Classical ‘Doe’

Mar. 1966 “Greater Breadth and More Variety”

As one can see from the titles of articles in the above table, An alternated from praising the North Korean political system to affecting the DPRK’s artistic and institutional practices of vocal music development. Following his death in 1980, An Ki-yŏng’s legacy has been defined in the North as

“spreading fundamental training [practices] in scientific vocalization for the first time” and “playing an important part in developing Korean music in a modern direction” (김득청, 2000).

Courtesy of the US Library of Congress

Conclusion

When considering why Kim Sun-nam faced persecution in the North as well as the South while An

ended up shaping music development in the North, one must consider political as well as artistic factors.

Before his defection, Kim was allied with the South Korean Workers’ Party under the leadership of Pak Hon-yong who was Kim’s primary rival in the latter part of the Korean War. An, however, was

more connected with the Laboring People’s Party that his mentor Yo Un-hyung founded. Even

though the latter was a more centrist party by comparison, it was not considered a threat to Kim Il-sung’s rule since Yo had been assassinated.

Furthermore, An Ki-yong’s artistic aims aligned with the North Korean leadership’s priorities more

than Kim Sun-nam’s did. Before and after liberation, An was interested in refining vocal technique

as well as adapting folksongs to Western-style music. Kim, on the other hand, was more interested

in compositional mastery and self-expression through music, which clashed with the North Korean

government’s agenda to create simple songs for the masses to enjoy and be persuaded with

As South Koreans are continuing to discover and appreciate Kim Sun-nam’s work, the previously

mentioned piece that An Ki-yong composed during the Japanese colonial period, “Longing for the

South of the River” has survived in the North as well as the South. Emblematic of a sin minyo or “new folksong” from the era, it is literally about looking over the Yangtze River in China, yet contains a hidden message about Korean independence. The place identified as “south of the river” was largely understood to refer to the area South of the Yalu River from Northeast China i.e., the Korean peninsula for those who were political and economic refugees in China.

Although tensions between the two Koreas remain high, the song’s pre-division yearnings for a

fully liberated nation could be rekindled for reconciliation in the future.

A South Korean performance of “Longing for the South of the River”

A South Korean video of “Longing for the South of the River”

About the author

Peter Moody(pgm2116@columbia.edu) is

a Visiting Scholar at the Seoul National University Asia Center (SNUAC) and PhD Candidate at Columbia University. Before that, Peter was an Adjunct Professor at the University of Maryland at Baltimore County and a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute for Far Eastern Studies, Kyungnam University. Peter obtained a MPhil in East Asian Languages and Cultures from Columbia University in 2019 and an MA in East Asian Studies from the University of Virginia in 2012. He has received a Fulbright award for his research on North Korean music, and his findings have been published in several journal articles and an edited volume. Peter has presented his research as a guest lecturer at a number of institutions and has also participated in academic conferences in the fields of Korean Studies, East Asian Studies, and ethnomusicology.

References

- 김득청. 2000. “조선음악의 현대적발전에 공헌한 음악가 -안기영선생의 생일 100돐에 즈음하여.” 음악세계, 30호, 95–100.

- 노동은. 1988. “민족주의 음악 창출, 양대 산맥 이룩.” (11월6일). https://www.arko.or.kr/zine/artspaper88_11/19881106.htm

- 노동은. 2017. 『인물로 본 한국근현대음악사』. 서울: 민속원.

- 배인교. 2012. “불후의 고전적명작 가요의 음악적 지향.” 북한연구학회, 6권 2호, 199–228.

- 오희숙. 2004. “안기영.” 음악과 민족, 28호, 66–99.

- 진회숙. 2013. 『예술에 살고 예술에 죽다』. 서울: 청아출판사.

- 『해방후 조선음악』. 1956. 평양: 조선작곡가동맹중앙위원회.

- Ahn, Choong-sik. 2005. The Story of Western Music in Korea: A Social History, 1886–1950. Morgan Hill, CA: eBookstand Books.

- Howard, Keith. 2020. Songs for “Great Leaders”: Ideology and Creativity in North Korean Music

and Dance. New York: Oxford University Press. - Hughes, Theodore. 2012. “Visible and Invisible States: Liberation, Occupation, Division.” in

Theodore Hughes. Literature and Film in Cold War South Korea: Freedom’s Frontier. New York:

Columbia University Press. - KBS. 1991. “월북작곡가 김순남 악보 발견 (12월7일). https://news.kbs.co.kr/news/view.do?ncd=3710503

- Park, Hye-jung. 2021. “Musical Entanglements: Ely Haimowitz and Orchestral Music under the US Army

Military Government in Korea, 1945–1948.” Journal of the Society for American Music, 15, no. 1, 1–29. - Szalontai, Balázs. 2005. Kim Il Sung in the Khrushchev Era: Soviet-DPRK Relations and the Roots of North Korean Despotism, 1953–1964. Washington: Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

- Zur, Dafna. 2017. “Liberating the Child-Heart.” in Figuring Korean Futures: Children’s Literature in Modern Korea. Stanford:

Stanford University Press.