LEE, Soo-hyun (SNUAC)

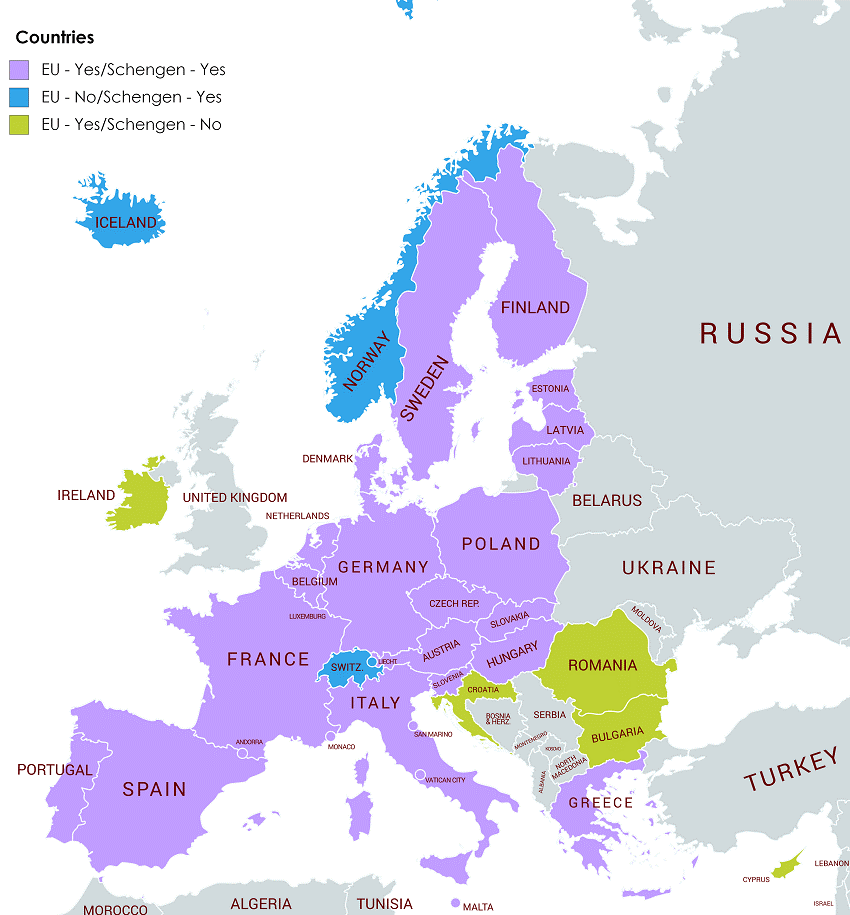

The European Union (EU) implemented the Taxonomy Regulation (EU 2020/852) in July 2020, an invariably crucial step in advancing the practice of sustainable investment in foreign portfolio investment. The purpose of the Taxonomy Regulation is to identify “environmentally sustainable economic activities based on technical screening criteria” against which entities seeking to make an investment under the jurisdiction of the regulation are met with an obligation to disclose both financial and nonfinancial key performance indicators, namely environmental impact.[1] These disclosures fall under the remit of related regulation such as the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and are performed in an “ecosystem of sustainable finance tools, including standards, labels and access to a coherent and relevant set of sustainability data.”[2] At the centre of that ecosystem, the Taxonomy Regulation identifies which economic activities, such as investment, qualify as being environmentally sustainable.[3]

However, the EU Taxonomy Regulation, as the largest cross-border governance mechanism seeking to establish legally binding standards of sustainable investment, has been met with resistance within its jurisdiction.[4] While the EU Taxonomy is still undergoing refinement, it would be difficult to deny its proliferating influence in non-European contexts where sustainable investment is experiencing rapid growth, such as in Asia.[5]

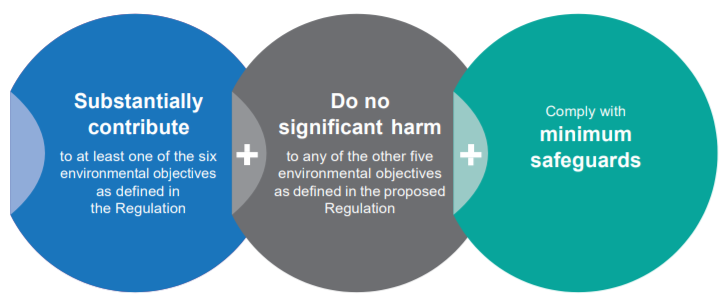

A fundamental precept of the taxonomy, the principle of do no significant harm (DNSH), is an inseparable element to the mechanics of sustainable financial regulation and as such will be woven into future taxonomies promulgated in Asia.

DNSH is identified in Article 3b of the Taxonomy Regulation, which states the following:

For the purposes of establishing the degree to which an investment is environmentally sustainable, an economic activity shall qualify as environmentally sustainable where that economic activity […] does not significantly harm any of the environmental objectives […]

When this reading is applied in the context of the environmental objectives of the EU Taxonomy Regulation, an economic activity, such as investment, would be in violation of the DNSH principle should it be proven to have done significant harm to any of the following:[6]

- Climate change mitigation, such as by resulting in an increase in the amount of covered emissions;

- Climate change adaptation, such as by resulting in reduced adaptive capacities of societies and ecosystems and exacerbating the adverse impacts of climate change;

- Sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources, such as by resulting in the detriment of the status and/or potential of bodies of water;

- Circular economy, such as by resulting in reduced circularity over the lifecycle of the good(s) and/or service(s) involved;

- Pollution prevention and control, such as by resulting in increased pollution of air, water or land; or

- Protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems, such as by resulting in detrimental effects to the condition, resilience, and/or conservation of habitats and ecosystems.

Essentially, the application of the DNSH principle takes places after the fact, in which retroactive assessment of DNSH is determined, or before the fact, wherein an economic measure would be denied on the basis of not being compliant with the Taxonomy Regulation.

While the implementation of a taxonomy regulation within a single state would not have the same international law implications as the regional jurisdiction of the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), its international law implications in general largely seem to be invariable. In other words, it would be safe to assume that many of key dimensions of the DNSH principle created through the EU SFDR and Taxonomy Regulation will be carried over into similar regulatory endeavours of other states, particularly those that involve regional harmonization and standardization. However, a major exception is undoubtedly the fact that the formation of a cross-border taxonomy requires a fairly deep level of economic integration such as that seen in the EU. From that purview, it becomes easier to identify the immense challenges that such an endeavour would face in other regions, such as in Asia.

The creation of a functional regional Asian taxonomy, or even a subregional East Asian taxonomy, will remain a long-term endeavour that requires constant adjustment to meet the constantly changing conditions of highly disparate economies. Significant development gaps and the lack of economic integration in Asia remains an obstacle to a substantial regional taxonomy taking form. Amidst these challenges, Singapore has taken the first steps at introducing a taxonomy regulation with its sights set on regional applicability in the ASEAN. Unlike other taxonomies that have been released in Asia, Singapore’s draft taxonomy regulation[7] was designed for regional implementation. While this is in part due to the transnational operations of Singaporean financial institutions, the drafters, the Green Finance Industry Taskforce (GFIT)[8] recognized that for any taxonomy to retain a high level of operability, it would need to be interoperable and to the greatest extent possible compatible with other taxonomies. For that reason, one of the core values of the GFIT is the extent to which the taxonomy is functional across a wide scope of jurisdictions.[9] To that effect, it identifies the EU Taxonomy Regulation as a clear benchmark for such endeavours[10] while also recognizing that lucrative trade and investment opportunities with the EU will now depend on compliance with the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). The draw-in effect of the EU SFDR has already had a ripple effect on Asian regulation. For instance, it has been reported that “70-80% of the Chinese standards for green products meet the EU taxonomy standards”.[11]

Source : www.mas.gov.sg

Another noteworthy aspect of the GFIT taxonomy is in its recognition that deference for the specific conditions faced by each country is essential to any taxonomy seeking regional or even cross-border application. A Singaporean financial institution operating outside of Singapore may observe a Singaporean taxonomy, but it will ultimately be liable to the laws of the country that hosts it—and this much is also recognized in the GFIT taxonomy.[12] For that reason, the GFIT taxonomy emphasizes the importance of core principles that would be indispensable to any sustainable finance regulatory framework, such as DNSH, irrespective of the peculiarities of the regulatory landscape that hosts and investor. The recognition of DNSH as a principle in the GFIT taxonomy resembles that of the EU Taxonomy Regulation. The GFIT identifies four environmental objectives,[13] but preconditions that any economic measure would not be compliant should it violate DNSH. One dimension to DNSH condition that the GFIT added, however, was that in addition to the interpretation of DNSH seen in the EU Taxonomy (“do not significant harm to any other environmental objective”), any measure that “contributes significantly to one of the listed environmental objectives but has a negative impact on the well-being of the communities in ASEAN” would also be in noncompliance.[14] This means that the applicable scope of the DNSH in the GFIT taxonomy extends beyond environmental objectives and that of social and governance dimensions.

This broadened scope of DNSH adds both considerable discretionary powers to the regulatory authority charged with implementing the GFIT taxonomy as well as burden to the investor in understanding the due diligence of their investment. By adding extra dimensions of complexity, such as a social and governance layer, DNSH is not solely the extent to which one measurable contribution to environmental objectives weighs against another measurable contribution to those same set of objectives. Instead, a measure, such as an investment, that may provide a substantial contribution to the pre-defined set of environmental objectives will then have to be assessed for its DNSH compliance against a set of social or governance objectives that may not have necessarily been identified in the taxonomy.

When DNSH is put into this three-dimensional format of environmental, social, and governance, it necessarily faces a similar trade-off between a wide scope against enforceability. While a wider scope provides greater coverage of the vast multidimensionality of sustainable development as a process, it also comes with challenges of equivalence between those dimensions that are difficult to reconcile. If the enforcement role of the DNSH principle is debilitated, then it will quickly be revealed that the entire regulatory structure of the taxonomy is nothing more than a Potemkin village; a perfect regulatory void for those self-regulating firms[15] that in actuality seek to freeride (while ultimately undermining) the necessity and promise of sustainable investment.

[1] Under Article 8 (“Disclosure rules common to all financial undertakings and non-financial undertakings”) of the Taxonomy Regulation.

[2] Delegated Act supplementing Article 8 of the Taxonomy Regulation, C(2021) 4987 (6 July 2021), p 1-3.

[3] Simona Petrisor and Amalia de Ligenza, ‘EU Taxonomy and ESG Requirements – “How Good Is Good Enough” and Are We There Yet?’ (Lexology, 26 July 2021) <https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=41f45a7f-d43a-431c-b492-aee76212f59d> accessed 28 July 2021.

[4] For instance, the inclusion of nuclear energy in the Taxonomy has been a controversial issue between environmental experts and the energy sector across the EU. See, for instance, ‘Unions Repeat Call for Nuclear’s Inclusion in EU Taxonomy’ (World Nuclear News, 27 July 2021) <https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Unions-repeat-call-for-nuclear-s-inclusion-in-EU-t?feed=feed> accessed 28 July 2021; Khalid Azizuddin, ‘EU Experts Threaten to Quit over Changes to Taxonomy’ (Responsible Investor, 6 April 2021) <https://www.responsible-investor.com/articles/eu-experts-threaten-to-quit-over-changes-to-taxonomy> accessed 28 July 2021.

[5] In a survey by Citi Asia Pacific involving 259 institutional investors, 94% responded that they either had or will implement ESG policies within up to five years from 2021 (‘A Time for Action: Opportunities for Asia to Further a More Sustainable Future’ [Citigroup 2021] 19). Financial institutions and corporations have been upscaling their ESG engagements as well. See, for instance, Kelly Ng, ‘For Asia’s next-Generation Leaders, ESG Is a Strategy to Push for Change’ The Business Times (7 July 2021) <https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/banking-finance/futureproof-an-esg-series/for-asias-next-generation-leaders-esg-is-a-strategy-to> accessed 28 July 2021.

[6] Adapted from ‘Technical Guidance on the Application of “Do No Significant Harm” under the Recovery and Resilience Facility Regulation’ (European Union (EU) 2021) Commission Notice C(2021) 1054 final 2.

[7] The public comment version is David Smith and Eric Bramoulle, ‘Identifying a Green Taxonomy and Relevant Standards for Singapore and ASEAN’ (Green Finance Industry Taskforce (GFIT) 2021).

[8] The GFIT was commissioned by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) as an industry-led initiative to develop a taxonomy for Singapore-based financial institutions. See Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), ‘Accelerating Green Finance: Guide for Climate-Related Disclosures and Framework for Green Trade Finance’ (Media Releases, 19 May 2021) <https://www.mas.gov.sg/news/media-releases/2021/accelerating-green-finance> accessed 18 August 2021.

[9] Smith and Bramoulle (n 7) 6.

[10] ibid 14.

[11] Karry Lai, ‘Asia ESG Standards Set to Advance with EU Taxonomy: Lund University Libraries’ (International Financial Law Review, 29 June 2020) <https://www.iflr.com/article/b1m0qkjg0xfg62/asia-esg-standards-set-to-advance-with-eu-taxonomy>.

[12] Smith and Bramoulle (n 7) 23.

[13] They are climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation, protect biodiversity, and promote resource resilience.

[14] Smith and Bramoulle (n 7) 23.

[15] In reference to what Short (2013) described as self-regulating firms operating in a regulatory void, or the lack of a “judicious regulatory regime […] with shared understandings about the rules of the game, adequate regulatory resources to implement and enforce the rules, and sufficient judgement to exercise restraint in deploying those resources” (Jodi L Short, ‘Self-Regulation in the Regulatory Void: “Blue Moon” or “Bad Moon”?’ [2013] 649 The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 22, 26). Short defined the “regulatory void” to “describe spaces in which government regulation, in particular, is perceived to be deficient” resulting in “bad moon self-regulation”. Of the types of voids identified, the a weakened DNSH mechanism would most likely fall somewhere between a knowledge void (“limited availability of information and strategic ways actors construct and understand it”) and institutional voids (“there is consensus on the rules or norms [but] competent institutions to enforce them may be lacking”) (ibid 27–28).

Works Cited

- ‘A Time for Action: Opportunities for Asia to Further a More Sustainable Future’ (Citigroup 2021)

- Azizuddin K, ‘EU Experts Threaten to Quit over Changes to Taxonomy’ (Responsible Investor, 6 April 2021) <https://www.responsible-investor.com/articles/eu-experts-threaten-to-quit-over-changes-to-taxonomy> accessed 28 July 2021

- Lai K, ‘Asia ESG Standards Set to Advance with EU Taxonomy: Lund University Libraries’ (International Financial Law Review, 29 June 2020) <https://www.iflr.com/article/b1m0qkjg0xfg62/asia-esg-standards-set-to-advance-with-eu-taxonomy>

- Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), ‘Accelerating Green Finance: Guide for Climate-Related Disclosures and Framework for Green Trade Finance’ (Media Releases, 19 May 2021) <https://www.mas.gov.sg/news/media-releases/2021/accelerating-green-finance> accessed 18 August 2021

- Ng K, ‘For Asia’s next-Generation Leaders, ESG Is a Strategy to Push for Change’ The Business Times (7 July 2021) <https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/banking-finance/futureproof-an-esg-series/for-asias-next-generation-leaders-esg-is-a-strategy-to> accessed 28 July 2021

- Petrisor S and Ligenza A de, ‘EU Taxonomy and ESG Requirements – “How Good Is Good Enough” and Are We There Yet?’ (Lexology, 26 July 2021) <https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=41f45a7f-d43a-431c-b492-aee76212f59d> accessed 28 July 2021

- Short JL, ‘Self-Regulation in the Regulatory Void: “Blue Moon” or “Bad Moon”?’ (2013) 649 The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 22

- Smith D and Bramoulle E, ‘Identifying a Green Taxonomy and Relevant Standards for Singapore and ASEAN’ (Green Finance Industry Taskforce (GFIT) 2021)

- ‘Technical Guidance on the Application of “Do No Significant Harm” under the Recovery and Resilience Facility Regulation’ (European Union (EU) 2021) Commission Notice C(2021) 1054 final

- ‘Unions Repeat Call for Nuclear’s Inclusion in EU Taxonomy’ (World Nuclear News, 27 July 2021) <https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Unions-repeat-call-for-nuclear-s-inclusion-in-EU-t?feed=feed> accessed 28 July 2021